What I'd like to do now is not just toss off the occasional hint in the midst of talking about something else. That's something every critic winds up doing over the course of any review. However, my focus today is going to be just a little bit different from all of that Instead, I'd like to take some time to actually share one of the tenets that underlies the work done on this blog. And the interesting thing is I know just the subject that will help me share all of this with you. It all has to do with a cartoon studio.

U.P.A. Cartoons: An Introduction.

As I've said, this post is really just a chance for me to explain a bit of where I'm coming from as a critic of books and films. I suppose another good way to say it is that I hope to get across my own aesthetic vantage point. In order to do that, however, I need some sort of art piece to work with. The task of criticism can never exist in a vacuum. You always need something to examine if you want to do a job like this right. What I've been looking for quite a while now for is some art work or text that could give the reader at least some idea of the kind of values I have and use when it comes to judging a story. In this case, what I've been searching for is anything that could help others understand my own relation (or lack thereof) with the question of visual storytelling. This is something everybody insists on as an important component of stories told on either the big or small screen. For the longest time, now, I've always found my own thoughts on the matter to be different. And I needed something, whether it be a book, or a piece of cinema history that would help me to explain my own, alternative point of view.

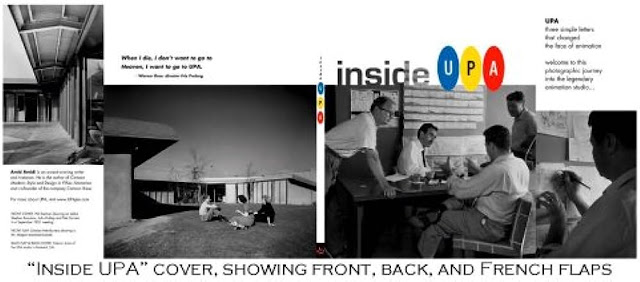

I think I might have found at least part of the answer for what I want to say on the matter of visualization in stories. It came from the unexpected help of the Royal Ocean Film Society, and a three part retrospective on what I think might now be a very forgotten, or at the least criminally overlooked indie studio known as United Productions of America, or UPA, for short. They were an animation house whose advent was in many ways the byproduct of a number of factors. Chief among them was the field or genre of the animated picture achieving its first, real, mainstream acclaim at the box office. There's more to this story than that, of course. What matters most about it all, for my purposes, is that I now have something to point toward that might help explain the way I relate (or otherwise don't) to the visual element of whatever stories I happen to like, and perhaps the work of UPA studios can help with at least the beginnings of an explanation for my own vantage point. In order to get there, however, will need to take a little tour of history into the life and downfall of a once influential film studio.

Part 1

Part 3

The Origins, Nature, and Art of UPA.

Something tells me I'd better apologize up front for those of you who bothered to watch the videos above. There may be moments here that will seem repetitive. These instances are written down solely for those who preferred to skip to the critique proper, without bothering to look at any of the evidence martialed above. Consider this a just in case heads-up. With that in mind, there's a surprising amount of things to unpack here. I'll start with a brief summary of UPA studios, and the cartoons they made. I'll then close things out with how their product ties into my own critical concerns, as it proves a handy reference point for one of the ways I approach the telling of stories. A lot of what I have to say about the animation company in and of itself is expressed well enough by the Royal Ocean Film Society video essay linked above. There, the history of this oft-overlooked company is described as follows:"This is the story of a group of rebels who changed the world of animation forever and for the better. The latter part of what I just said is partly my opinion, but hopefully I can convince you that I'm not too far from the truth". It's the kind of proclamation whose only purpose seems to be for the sake of getting shot down, and tossed away into the gutter. Still, the documentary continues to press on from this somewhat hubristic beginning to tell a bit of the facts. For instance, they chronicle that the UPA studios had its start in the early part of the World War II 40s, and continued all the way until about the same time as the Beatles broke up. Way back in 1970, this would have been. "In their own time, they completely upended every conception of what animation could be, and turned it on its head. Creating for themselves a legacy that has kept their work alive ever since. The UPA-ers were titans, rebels, artists, and innovators, and this is their story". The punchline to all of this sort of rests in the way that UPA ultimately came about. If the creation of the then new enterprise can be counted a success story of a kind, then one of its unintentional lessons has to be that if you want to help foster the creation of a new, independent animation division, all you have to do is make sure to piss off your staff.

This is something Walt Disney, of all people, fell into during May of the year 1941. Now to be fair, everything I've read or seen about the incident I'm about to relate next leads me to believe that Walt never meant to alienate anybody. It also, however, went to highlight one of the animation pioneer's few weak spots. The honest truth seems to be that Walt had two main strengths. The first was a knack for having a very creative imagination, and then being able to pick and choose the cream of the crop to help him bring the pictures flitting around inside his head to a kind of vibrant, imaginary life. That's how Disney managed to build up his company. He would keep an eye out for animators whose style and technique showed signs of potential, or else whose talent was undeniable, and then try and see if they would come and work for him. This was no small feat on his part, and it highlights the second of Walt's main skills, his knack as a deal maker. He was nothing if not a good salesman, however, it was the one talent that seemed to come with its own built-in limitations. While Disney was good at being a builder, there were plenty of times when it was clear he didn't have as good a had for business as he should have had. It was his one major weakness and this time it got him into trouble with his own animators.In retrospect, perhaps it was a case of too many conflicting demands piling up in a situation where no one would have ever really been able to get whatever they wanted. You see, the animation staff at the Disney studio, the guys and gals who had helped Walt bring folks like Mickey, Donald, Goofy, Snow White, and Pinocchio to the big screen where starting to feel a certain amount of fatigue with the way things were going at work. All of it ultimately centered around a question of the paycheck, and therein lay the crux of the matter. The employee's needed a bump in their income if they wanted to keep afloat at the same time that the studio they were working for was beginning to think the very exact same thing. The punchline here is that by now Walt had managed an ironic achievement. All of his major entries to date had been critical successes that had allowed Disney and his company to place their name on the map. On the financial side, however, Walt and the studio were facing a number of setbacks. This included a contract with the studio's distributor, RKO Pictures (a company which no longer exists, by the way, even if they did help release Snow White), plus an unexpected freeze on all overseas income from places such as Britain, France, and Germany, as the oncoming War put a financial sinkhole in the studio's earnings. This left Walt clueless, and with an untenable, unworkable situation on his hands.

His animators wanted more pay that he couldn't give them. They wanted more credit for their work, which in turn meant more income that wasn't available at the moment. So that even though Walt would later go on to grant all of these demands, it was an impossible promise to make, at least at that particular moment. To top it all off, the company itself was sort of taken out of Walt's hands when the U.S. military stepped in and commandeered the studio, it's buildings, sound stages, and lots for the purposes of helping in the war effort. This provided Walt with enough easy income to stay afloat, and that's all it could do. Momentum on whatever animated features had been ongoing at that point came to a halt. A great number of the former staff had to be let go. The only material that could be focused on at this time was a handful of Mickey, Donald, and Goofy cartoons, with the only major motion picture entry of that time being Dumbo, which was the only safe option left after the failure of Fantasia the previous year. The rest of the studio's time and effort would be spent on churning out a lot of propaganda short films meant to boost the Country's morale for the War effort. It was the kind of situation where something has to give, sooner or later. In this case, it was a walk out of staff.

It was perhaps the lowest moment of Walt's life, and I think what it highlights most is the point at which his strengths as a businessman come to an end. The trick with the old Mouse House was that its priorities were always sort of split down the middle. Walt was the dreamer, and his brother Roy was the one in charge of keeping the company afloat. This often meant having to scrounge up funds for his little brother's next flight of fancy, and there could sometimes be a certain carelessness in the way Walt pursued his dreams, even during what is now seen as the company's golden age. The fact is Walt was always better at being a Romantic than he was an administrator. The War years sort of forced him to gain a crash course level of experience in this regard, yet by the time the lesson had been learned, the damage was done, and a few employees who had been there with him in the beginning had moved on to pastures of their own. What happened next is that these walk outs from the House of Mouse, a group that included "story men, layout artists, in-betweeners", and "animators" all wound up meeting together to discuss what, if anything, might come next. Their informal headquarters of the moment was the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, and one of the leaders of this meeting was named John Hubely."Hubely's complaints didn't just stop with pay or credit disputes. See, he was part of a growing number of animators who had grown entirely bored of what the big animation studios were churning out. 'The marvelous training at Disney developed your imagination and ideas, which were then inhibited by the need to conform to a standardized style. We just got so sick of humanizing pigs and bunnies...Select any two animals, grind together, and stir into a plot. Add pratfalls, head and body blows, and slide whistles for taste. Garnish with Brooklyn accents, slice into 600 foot lengths, and release". The review, however, claims "it went much further than that". And it is here where things get close to my own way of reading a work of art, whether on the page or screen. "If there's a spectrum that has abstract art and realism on either end, Disney in the 1930s sat far too comfortably to the right for Hubely's taste.

"It was that Snow White and the Prince not only looked very much like humans, but also moved pretty much exactly how humans do. Which, impressive as that was, and is, was an attempt to push the look and feel of animation closer and closer to live action. Whereas Hubely wanted to go in the exact opposite direction. He didn't want his animation to look and behave like live-action. He wanted his animation to do what live action couldn't. His colleague Zack Schwartz (explained, sic) 'Our camera isn't a motion picture camera. Our camera is closer to a printing press'. Their films didn't have to be films in the three-dimensional, live-action sensibility. There was an entire world of unexplored graphic expression, and like Jazz, modern art, or method acting, Hubely saw an entire world divorced from traditional conceptions of artistic realism that was begging to be embraced". Hubely, his friend Stephen Bosustow, and a handful of other Disney vets who left the company got their first big chance to take a shot at the kind of animation they wanted to see from what has to be the most unlikeliest of places.

It was while serving in the U.S. Military during World War II that Hubely and the crew that would go on to form the nucleus of UPA would ironically get their first true taste of artistic freedom. For a bunch of enlisted grunts who were hired on to do little more than propaganda animation for the War Department, the powers that be were surprisingly hands off on how Hubely and the others went about their assigned task. The thinking seems to have been: "As long as you can either stick to the script, or at least suggest a usable idea for our purposes, then have at it. We don't really care how you say it, just so long as it stays on message". It's a fair bet that this is not the sort of carte blanche deal that any artist today could expect to get from the Armed Forces, which makes the opportunity that the future UPA crew was given all the more remarkable. "Ironically, many of the animators found that they were given freer artistic reign than they'd ever received when they were working for the top studio dogs. But with that free reign came a massive caveat, one that forced the artists to find newer, faster, and cheaper ways of telling stories and communicating ideas. And the result was raw, artistic innovation. "It was the working world John Hubely had always wanted". During this time, Stephen Bosustow created the prototype studio for what would later become UPA, the Industrial Film and Poster Service. "The year was 1944, and the company's first few gigs were propaganda paid for by the United Automobile Workers". It was this initial round of early gig economy work that both helped Hubely and Bosustow pay the bills, and the staff, as well as allowed the animators to stretch their visual imaginations. The new studio's first major achievement, Hellbent for Election "was baby steps. For the real triumphant leap came with the company's next films". The entry Brotherhood of Man represented not just a technical but perhaps (some may argue) a kind of social leap forward. The entire cartoon short is an 8 minute treatise on race relations that is surprisingly resonant for the time is was made in, and the real feather in the cap is that Hubely and the future UPA staff do not condescend or denigrate when it comes to the depiction of other races. Instead, all of the character models maintain a laudable respectability.

It was "a cheerful instructional on tolerance and diversity. and it was the culmination of what Hubely had been working towards. In his words, 'A total breakthrough from the Disney style'. It was the flat, sharp layouts. The striking designs that left the background interpreted through only the simplest color and curve of the line, and the dynamic visual storytelling. These were conceptual ideas turned into images, and breathed into life through the magic of animation. And there wasn't a talking mouse or singing tree in sight". It was perhaps an opening salvo of sorts, though it might be telling to consider just how few people out there know of it at all today. Whatever the case, the facts of history remain the same. After the War, Bosustow opened a new company for Hubely and the ex Mouse animators, this time christened United Productions, and the rest has since gone on to become history, albeit a very overlooked one. What matters for the rest of this review is the UPA style and what it can tell us about the different ways of looking at a visual work of art, especially as it relates to the other art of reading.

The first two years of the 1950s proved to be UPA's watershed, as "they released two separate films that were both wholly radical in their own proper right. The first, Robert Cannon's Gerald McBoing Boing, based off of the Dr. Seuss story. A triumph of color and layout that wouldn't have looked out of place hanging in a museum right in between a Picasso and a Matisse. It was the way the color of the background blended in with the character's skin tone. The way that backgrounds and locations were stripped of detail. A suburban home designated by only the odd door-frame or lamp, here and there. It was the low, striking angles, and the way that shots morphed into each other rather than being cut.

"All of this being complimented by the sophistication of the second film: John Hubely's Rooty-Toot-Toot. Based on the popular song, Frankie and Johnny, a ballad about a love affair that culminated in violence. Here it was a triumph of character and design. A perfect marriage of Jazz, dance, and color that tied movement to music, and each character to a different instrument. All while the entire frame was, again, stripped of detail, but in effect made all the more striking and bold. Practically demanding and owning one's attention. These were cartoons as art. In the capitol lettered, unashamedly pretentious, fuck you, we're doing it the way we want to method. The kind of thing people post as #aesthetic. 'An innovation', as Dan Bashara described it, 'based off of creativity, ideology, and financial necessity. It was UPA". So what does all of this have to do with the way I read any given story? Then there's the most important question to ask. Is the product churned out by UPA any good at all?

Conclusion: Overlooked Gems, and a Testimony of Personal Aesthetics.

I think I'll answer the second question first, and start by saying that yes, the UPA cartoons are things that I would give an easy enough recommendation to, with one caveat. That you see how far you can stretch your current, 21st century imaginative sympathies. This is not a trigger warning notice, by the way. There's nothing offensive in these old theatrical cartoons. Instead, it's more a matter of finding out where the current audience stands in relation to older entertainment that isn't racist, merely different from the current expectations. This difference rests nowhere in terms of offensive characterization, and resides instead with the more complex matters of style, pacing, and overall presentation. Here is where the crux of this whole matter comes into play, and it's a struggle to find the right description for it all.If I had to find the words to sum up the UPA style, then it might be to term it all as Abstract Surrealist Minimalism. Another way to say this is that it is perhaps the closest representation of what the initial draft of a creative idea looks like in the mind of the artist. This is the point at which the barest bone, sketch, and outline of the characters, background, and even the plot are starting to take shape. As the writer begins to get as clear a vision as he can of the work, then the pictures in his head begin to fill in, and take on a greater sense of shape and solidity. Now what the UPA crew do is something interesting. They will do all the work necessary to make sure the story proper is as complete as any of them can possibly make it, whether it be a story about a fox and a crow, or a fable drawn straight from the pages of the New Yorker. The interesting thing is while the story gets completed, the outline and shape of the characters and setting are always left vague. If you took and novel like The Grapes of Wrath, and gave it to UPA studios, the Joads and their narrative journey might all be there intact. It's just that the style would be so minimalistic that it would be like watching abstract figures in a medieval tapestry come to life. In the strictest sense, there are no human beings in a UPA cartoon, just characters and events.

The Ocean Film Society likened UPA's work to that of paintings in a museum come to life, and it's one of those cases where the more you keep examining the cartoons put out by the studio, the more comparison seems not just apt. It's also perhaps a literal description of what happens on-screen whenever Hubely and his animators are in control of the canvas. The second video essay above puts the whole thing in what is perhaps the best perspective possible, at least at the moment. "All of this was wrapped up in the popular Modernism of the mid-twentieth century. Saul Bass; Frank Lloyd Wright; the French New Wave; and if there's a label we can apply to what UPA brought to the arts and crafts table. If we can summarize all of the philosophical gooiness that animator John Hubely wanted to chase after. Then it's what's come to be known as limited animation. An ideology heavily informed by...The Language of Vision, by Hungarian born painter and theorist, Gyorgy Kepes. Who advocated for every unnecessary detail to be eliminated. There is no time now for the perception of too many details. The duration of the visual impact is too short. Clarity, precision, and economy are compelling values in a world suffering under the dead weight of undisciplined individualism", Kepes claims.I think the Ocean Film Society has done readers a bit of a service here. As the citing of Kepes and his work of artistic criticism serves to ground things in an actual working theory of art. However you want to regard the UPA style, whether you find it inspiring or dull and insipid, there's no way you can claim it all as the product of artistic laziness when the entire thing is itself inspired from a genuine theory of what art should be. The theory itself may serve as a headache to some. Yet it's ideation and practice remain real for all that. The ironic thing to note is that a respect for the individual artist was the one aspect where UPA seemed to diverge from Kepes' theory. Otherwise, both theorist and practitioners seemed to be united on more or less the same, minimalist page. "Here at UPA, they're all about the artists. So if you want to build a cartoon you got to start with your crew. Maybe John Hubely is off busy upending all manner of tradition. So you hire Bill Hurtz, who gives you a play on James Thurber's classic fable about a man, his wife, and the unicorn in their garden. Maybe you think it ends up being a little too adult, but learn to deal with it. Because a lot of UPA's films tend to lean that way.

"Infidelity, neglect, murder, all fair game. Maybe you hire Ted Parmelee to bring Edgar Alan Poe to life in a style one page away from Salvador Dali. Because you want to give your audience, regardless of age, horrific nightmares for the next two and a half weeks. Or maybe you hire Robert Cannon. Since he's hands down UPA's best working director. If John Hubely was the one who set up the ball with all his ideological radicalism, then Cannon was the one who spiked the heck out of it. His wasn't the crash, bang, boom world of Warner Bros. His were stories about families, domestic life, and parent-child relationships. Classical parents clash with Jazz children. Little Christopher is an absolute terror" who for some reason is obsessed with owning a real rocket ship, instead of a toy model (how or whether this kid gets one is a story that deserves not to be spoiled). Meanwhile, a hen-pecked husband and father named "Fudget has to follow a budget. And unlike Mickey, Daffy, or Woody Woodpecker, Gerald doesn't want to be special or extraordinary. He just wants to be normal. Cannon's was a soft approach to animated storytelling. Struck sideways and blown into something astronomical with damnedest visuals the medium had ever seen. It was the abstract, photo-negative world of Fudget's budget.

"The warm, storybook color pallets of the Gerald McBoing Boing films that would make Wes Anderson drool. The flat, anthropomorphic, stop-motion of The Oompahs. And the smudgy impressionism of Madeline" (based off of the award winning children's book of the same name). "(Cannon, sic) was UPA's grand experimenter, and one of the all-time, underrated masters of the medium. Each world he and his compadres created was separate, unique, and beautiful in its own right. To design those worlds, you've got to hire someone like Paul Julien or Jules Engel to take care of the color. And because their work is so vital to the film, we do what Uncle Walt never did, and we throw them a bone in the opening credits. We're all about keeping things cheap here at UPA, so as much as you can, you've got to limit everything you throw up on the screen, including color". The second video then arrives at the final point which is also the crux of their documentary. "(Like) everything else about these cartoons, you'll find that less is way, way more. Cut corners by eliminating skin tone, and have those background colors bleed through. When you get comfortable with that you can really start playing around. Nothing's clean here, like a bunch of kids drawing outside the lines with crayons, leaving splotches everywhere.

"Don't worry, someday a bunch people will stroke their chins and glorify it with the term Minimalism...Now remember we're not after anything resembling Realism. We're not looking at people like Edward Hopper or Gustav Courbet for inspiration. We're looking at people like Charles Demuth or Kandinsky. But more importantly we've got a pile of New Yorker issues sitting in the corner. So we steal everything we possibly can from Saul Steinberg. It's all about what we can do and say with simple shapes and textures. The very angle and curve of a line, and that goes whole hog for the animation as well". One character, for instance, will "devolve into a mass of squiggles when he transforms. Sonic circles denote the blast of a (car) horn. The characters" in another cartoon will "morph into lines to move about the frame". I've quoted at such great length from the documentary above because I wanted to make sure the reader gets as close to a clear picture as possible of the kind of outside the accepted norm house style that UPA took as its own standard. If it plants any notion in the collective mind of today's audience, then it might conjure up the image of a sketchpad gone wild and untamed.

If this is all you can imagine based off of just a bare bones description the studio's avant-garde creative strategy, then I won't be too surprised if all this stripped down approach to visual storytelling language leaves one with the vague impression of a jumbled, indefinable muddle. It's as if the Ocean Film Society is trying to describe smoke, something that can't be seen real well, and is impossible to pin down. If this is all the audience is left with, then none of it surprises me, because of what it is able to tell the astute observer. For me, it speaks of just how far the audience has gone in the exact opposite direction from the aesthetic outline sketched by Hubely, Cannon, and Bosustow. If you say the word animation today, or ask who makes the best animated films, then you're likely to get one of two answers. A small segment of the audience will reply that it's no contest. Disney and/or Pixar remain the undisputed champions of turning cartoons into the movies, though there may be some murmur that the titan is in danger of turning into a shell of its former self these days. The rest of the audience, which makes up a majority that far outnumbers the fans will admit they have no idea what I'm talking about.

The majority may also go further and ask what seems a very commonsensical question, at least as far as they are concerned. "And anyway", they'll say, "who on Earth cares for a bunch of cartoons, anyway? It's all just the stuff you turn on in order to keep the kids quiet for however long you need to make sure their bellies are well fed, and they can go on having a place to live. The inarticulate assumption of the majority is that with the daily task of survival staring you in the face the moment you open your eyes each morning, who has time for either cartoons, in particular, or make-believe in general"? It's the kind of sentiment that's bound to shock any die hard Pixar fan out there, for the record. What it also tells me is just how unlettered the vast majority of the audience is, and has been, for quite some time now on just how many ways there are of reading a story besides the current zeigeist in which we live on a very unconscious level. This is something that begins to be driven home for anyone who is willing to stop and take a look outside the box that is our contemporary reading habits. It's a lesson that has been brought home to me not just through studies of long, forgotten film studios like UPA, either. In fact, a surprisingly greater scope, or perspective on the way we perceive the art we create can be found when you turn from mere film studies to criticism that deals with creative writing. It's the kind of notion that is so counter-intuitive to how we think today, that it's no wonder if few have ever considered there might be a handful of literary critics out there who can help us understand that our current way of looking at stories is not only relatively recent, yet also subject to shifts and changes with the passage of time. This is something I learned not just from filmmakers like John Hubely, but also decorated literary critics like Alastair Fowler. If you're lucky to find the time, try and hunt down a copy of titles like Kinds of Literature: An Introduction to the Theory of Genres and Modes, or Renaissance Realism: Narrative Images in Literature and Art. Both texts are good places to arrive at a gradual realization of just how often our conception what is the "right" or "proper form of dramatic presentation" has not, and probably never has been the same as the current set of artistic expectations we bring to storytelling.

What critics like Fowler, E.H. Gombrich, or Erwin Panofsky can help us realize is not just how our understanding of what makes a "proper narrative presentation" has never really stood still over the years, regardless of medium. In addition, they can sometimes help us recapture a sense of how older audiences were able to enjoy the favorite stories of their own, long gone time periods. A final bonus here is that they can also make us realize that our current way of seeing and appreciating the books and films we like are also just as much of a phase that is having its day for the moment, until the turn comes when it too will give way to a different way reading and seeing on an imaginative level. Here's Fowler's point in a nutshell.

While it's possible to point to a kind of teleology in the history of artistic representation, there is nothing inherently progressive about it. It is less a matter of forgone destiny, and more a question of choice that applies to both the artist and their audience together. Indeed, it is not too out of bounds to consider that we might now be living through an age of mixed old and new aesthetic expectations and generic narrative practice's, with both modern and primitive reading and storytelling techniques existing together side by each. All of this taking place on such a submerged mental level, that our conscious minds can barely register the differences and clashes that make up the current moment of artistic cognitive dissonance. It takes a very determined effort to break outside of the viewpoint box we are currently in. This is the sort of achievement anyone can make in theory, yet very few of us have tried in practice. Leading me to wonder how different things would be if the majority really managed it?As things stand, all I can do is give a field report from outside the box, and let everyone else on the inside know how things are like once you've been able to take a step back, and look at both art and audience with a greater critical scope. From where I'm situated, what I'm looking at is an audience whose fundamental artistic assumptions rest on an uneasy, unstable kind of narrative realism. This is less a well held together, coherent thought, and more a haphazard set of notions that have accumulated together over the years. Most of it shows signs of being drawn from the Ivory Tower, of all places. It's a case of the reigning zeitgeist of older critics from the 19th century, such as John Dewey, trickling down into the larger public mindset, and thus conditioning the audience's expectations for literal generations. The irony here is that while someone like Dewey might be able to construct a long thought out rationale for why a narrative based on a Naturalist mindset makes for the ideal type of narrative storytelling, the vast majority of the people out there, in the aisles, cannot justify such a belief however they want. Instead, it's a question of the long, worn out opinions of an earlier age filtering in among the readers in a highly debased standard.

Much like John Hubely, I find myself confronted with a way of looking at things in general, and stories in particular, that is long past its due date. It seems that the time is ripe for a change of audience perspective, yet we seem to be in a holding pattern for the moment. That new insight which will help us look at, or read stories in a fresh way has yet to materialize. If and when it does, then as the saying goes, everything old may be made new again. Until such time, I find myself having to look for ways of conveying a more outside the box way of dealing with the fictions we write for ourselves. It's not an easy task, by any means. The funny thing is how it is still possible to say this is one of the most stimulating tasks I've ever tried to shoulder in my life. The good news in all this is that I've never had to do it alone. Guys like Hubely, Bosustow, and Cannon have been a lot of help in this. Without setting them up as any kind of gold standard, or anything. What I am able to say with a fair amount of certainty is that the animators and artistry of UPA has done a critic like myself a bit of a double service.

In addition to churning out some pretty impressive cartoons that don't deserve to be forgotten, they've also perhaps managed to set up, not a goal post to aim for, so much as helpful sign or bus stop along the way. What the efforts of artists like Hubely, or critics like Fowler and Panofsky have helped me in understanding is the need to never rest cozy with any potential visual style when it comes to picturing the stories I enjoy. I don't know how strange of a thing that is to say. All I can say is that it has helped enrich my ability to take in a ton of different types and styles of stories beyond the ones that exist at the current (and right now, somewhat precarious) blockbuster box office. And part of the debt is owed to the animated secondary worlds created by UPA. What all of this has helped me realize is that visuals count for a lot less than the quality of the writing. Perhaps it helps to think of it as a way of reading that refuses to be boxed in. It never rests on a specific style of visualization, and instead knows the real smart choice is to just leave the table open to a lot of different voices, vantages, or perspectives. Whatever the case may be, or however you think of this, the uneraseable fact behind all of this theorizing remains the same. I can never judge films as good or bad based on the way they looked. Instead, it has always remained the skill on display in the writing which has been the ultimate decider in whether I look at any book or film as bad. This is something that has born itself out for me in practice, time and again. There have been a number of films with great visual styles which have nonetheless left me bored to tears because the script was never anything worth bothering about. This has been true even in a number of films that have long since been considered classics. The titles among this ironic list includes such names as A Nightmare on Elm Street, Vertigo, 2001: A Space Odyssey, the Disney Star Wars trilogy, Ben Hur, Tenant, and a lot (if maybe not all) of Ingmar Bergman's films like Persona and The Seventh Seal. I just can't get into any of these works because while the cinematography is some of the most impressive work ever done, it stops at being just a nice coat of paint with nothing else to recommend it. Then what happens is I'll turn around and watch a cheaply made Vincent Price flick, or a simple, straightforward rendition by UPA of James Thurber's Fables For Our Time, and come away with the kind of story whose enchantment will be able to last maybe more than just one lifetime.

To me, the whole thing has amounted to one ongoing lesson that looks are never the whole story when it comes to judging the quality of either a book or film. All stories are at the mercy of the writing. This is something that was born home to me the more I studied the history of how audiences or readers related to the stories they were told. I've even boiled it all down to a kind of maxim within a proverb. No one has ever been able to leave the theater stage, and the stage itself has never been able to leave the page. All narrative depends on the written word for its existence, and even that resides ultimately in the mind, seeing as how art is the ultimate product of the Imagination. What all of this has left me with is an aesthetic outlook that has offered me a greater degree of freedom from the kind of established norms that have been dictating the way we read and/or watch the tales we tell ourselves. It's also gone that one step further by helping me realize that even the current gold standards we use to judge a work of fiction will always one day be replaced by another. I seem to have found an ideal vantage point for this. As it's one that exists outside of all standardized styles of visualization, and it might be true that the UPA cartoons have turned out to be at least one of the helpful guides towards this realization.

So does this mean I'm willing to recommend the studio's cartoons to the audience? Well, I'd have to say yes, they deserve to be rediscovered and given a look. The trick is knowing whether or not the current reigning tastes of the audience will even permit such a thing, at least for the moment, anyway. If there's one thing half a lifetime of paying close attention to trans-medium "texts" and the way they are "read" has taught me, it's that the full import and content, or meaning of the words in any given story can never be taken in at a single glance. The other lesson life has taught me on this score is that the audience can never see whatever it wants, only what it is capable of perceiving in any given narrative. This can have a vert crippling effect on the reader's ability to properly enjoy any story. Indeed, it is possible that such circumstances can lead to unintended, yet very unfortunate effects. It is not impossible for a reader to have a copy of Dickens' Great Expectations (or one of the best of its many adaptations) placed in front of them, only for the audience to come away bored, because it doesn't match the current style of storytelling that they are used to receiving. This may sound strange, yet really it's what to expect.What happens in this case is there are a number of competing factors at work here, each one serving to cancel the other one out. On one hand, you have a complete text which time has proven to be objectively good. In other words, the first ingredient in the equation is a legit great story well told. The second component, however, is not just the audience, but also whatever artistic expectations of the moment that have been slowly accumulated and acclimatized into their minds as they have grown from infancy to adulthood. It's a process that happens in every age. Up till about the 19th century, however, it was possible to claim that readers grew up under a relatively stable and unified sense of artistic expectations. This is a mindset that has apparently undergone some kind of shift or breakdown. Meaning that we now live in a situation where in order to gain any possible appreciation for a work like Great Expectations, or a simple UPA cartoon, the audience would first have to undergo a much slower, halting, maybe even somewhat awkward process of acclimatization in order to be able to fully appreciate the genuine art of the creators that went into the finished product as a completed whole.

If that sounds like a lot to ask from the next faces you see in the aisles, then perhaps that's true. Like I said, there seems to have been a breakdown of some kind in an audience mindset that once possessed a greater sense of shared artistic expectation. I suppose another way to put this is that readers used to possess a greater deal of imagination, once upon a time. In recent years, however, say, sometime after the turn of the millennium, this imaginative capacity has begun to shrink. What's more worrying, this reduction, or imaginative sterility appears to have occurred in spite of the best efforts that genuinely knowledgeable teachers and educators have made to counteract it. This has left the artist of today in an unenviable stuck position. They're forced to play an unintentional game of catch as many readers, or eyeballs as they can, and who can say how well even the most accomplished storyteller will fair in the contemporary climate? For instance, I once saw a review on the films of Akira Kurosawa, and while it was clear the critic was a genuine fan of the director's work, he was also aware of how few modern viewers out there would be capable of even caring about one of the creators of contemporary cinema.

This seems to be the challenge that all art, whether classic or contemporary must labor under, and the cartoons of UPA are no exception to this somehow unstated, yet very real (for the moment, anyway) rule. Because of this, I'm going to have to be very careful in how I recommend a series of short films like these. Are they worth watching? Absolutely. In fact, it is possible to argue that they are just as good, in their own right, as a book like Great Expectations. It's just that now you have to temper those expectations in terms of the possible reception they can get nowadays. I write this all from the perspective of someone who wants to see the legacy of UPA continue on, in the hopes that it can inspire a future generation of writers, artists, and animators out there. In much the same way that the art of Max Fleischer has gone on to inspire contemporary popular works such as the Cuphead franchise, so the work of John Hubely and Robert Cannon has the potential to act as an inspiration for further artistic endeavors in the same vein. In order for any of this to happen, though, all art now seems to require a bit of education on the part of any interested segment of the audience, if they are to be really understood.From here on in, it really does seem as if all proper appreciation of the arts and storytelling has become a matter of what E.D. Hirsch described as Cultural Literacy. We seem to have reached a point at which there is a disconnect between artist, or writer and audience. It seems to be a case where the artist is often creating their art from a perspective of background information that is often in danger of being alien to most readers and viewers. This puts all art at a disadvantage, as it means both parties will get left out in the cold unless some effort is made to bridge this gap. In the case of UPA, this means finding out how to learn about the artistic principles that undergirded its unique style of telling stories. "These were Modernist worlds. Worlds that quite often followed one of Modernism's central tenets: self-consciousness. There were animations that were frequently about the very fact that they were animated. Or as John Updike described it: 'contained within them the need to confess artifice".

What I've begun to learn from all of this is just how much the current process of understanding (or lack thereof) of the art of storytelling mimics the current clashes that are rocking the entire world today. It leads me to wonder; what if the possibility of being entertained by stories rests on a similar need to understand the vantage point of another person? The importance of such a possibility would of course be doubled if the artist is from a different culture altogether. If there is any truth to this surmise, then maybe one of the unintended side benefits of discovering the art of a simple UPA cartoon is that by helping us to gain a sense of the history of our own culture, it can then help spark the curiosity to learn about those of others, which might just turn out to be a very necessary skill in the 21st century. Perhaps this sounds like a lot to ask from just a handful of animated cartoons. All I can respond to this is that it seems as if the demands of just plain living in the current moment is now demanding that all citizens in audience learn a greater deal of knowledge about the world and the people in it, if we wish for stability.

The demand itself might seem strange, yet its fundamental logic is sound. Not only that, but it's also true all good works of art can be of help in this regard. The only trick to keep in mind seems to be the need to tell the difference between a genuine expression of art, and the false pretenses propaganda. True art always opens doors to a fuller understanding life and all the people in it. All propaganda is concerned with is the will to power, thus entailing a very narrowistic conception of what life is, or could be. Besides, it's also something that means to get other people hurt, and that's the last thing that any true art should have as its goals. All that guys like John Hubely and Bob Cannon cared about was telling goods tales that could help widen the expanse of the imagination. The artwork may look crude or passe from a viewpoint that has been raised to view all animation from the Pixar reference.

However, I'd argue that's exactly why the work of UPA can help serve to shake us out of such sterile complacency. It might help give us a sense of the other frontiers out there waiting to be explored. For all of these reasons, I'd have to recommend that you hunt down the work of the UPA cartoon studio. You might be surprised at the way it has of helping to expand the horizons of your Imagination.

_(Taken_from_The_Gerald_McBoing_Boing_Show).png)

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment