Like I say, I can't really tell anyone how common this particular type of reading practice is. I just don't know how many others study the narratives they like in the same way that I do. So it's kind of useless to ask me if this is anything like part of a greater phenomenon of literary practice. All I can tell you beyond this point is that this is what happened to me when I had the good fortune to read first an old, forgotten poem (I guess you could call it a children's rhyme), followed by song, also old, this one dating back to the start of the 70s. The name of the poem was Antigonish. It's one of those titles that no one remembers, even while there's something memorable about it. The sort of thing you hear in passing, and then wonder why the word popped into your head later on. The almost limerick style composition was written and published in the year 1899 by a now obscure poet and educator named William Hughes Mearns. The song that helped me understand Mearns' poem was The Man Who Sold the World, by David Bowie. I'm sure that's a juxtaposition few if anyone reading this would be expected to make. I know I wasn't. For the longest time, this forgotten poem and the chart topping song were complete and separate entities in my mind. I ran across Mearns' work in a collection of children's verse in an illustrated primer book whose title I know forget, except that it was edited by Jack Prelutsky.

The Bowie song I ran across by seemingly pure chance one night while staying up late watching a now defunct VH1 programming block. It was an entire program or segment dedicated to music from the 70s, as I recall. Somewhere between Ozzy Osbourne's Iron Man and being introduced to the music of Leo Sayer for the first time (yeah, VH1 was dedicated to it's eclecticism back then) someone in a broadcast booth somewhere made the now wise choice to air an old live performance that Bowie gave of the song way back during a 1995 MTV concert special. It was one of those things where at the time it had no greater meaning than just a way to enjoy a few minutes before dozing off to sleep. It was the kind of thing I caught once or twice, enough anyway, so that the song got lodged in my head. The sort of tune that recalls itself to your conscious mind, and you sort of remember it as being kind of interesting, yet you still don't attach all that much importance to it. What changed that for me was running across that song again in connection with Mearns' bit of poetic doggerel. What I didn't expect to happen was for Bowie's lyrics to help inform the meaning of Mearns' little rhyme. The result wound up as something that was less a pair of unrelated verses, and more like a complete and greater poem told in two movements. That's how I'd like to look at each effort, as two parts of a greater whole.

I do this first because the ideas that came about from pairing the efforts of these two artists in my mind suggest a rich vein of thematic ore that is just too interesting not to share. Another reason for looking at these two poetic attempts together is because each of them seem to share the same genre. In many ways, the placing of Antigonish and The Man Who Sold the World together is to create the kind of narrative that is more or less perfect as we get into the Autumn Festival season. What we have here is a kind of ghost story that I don't think either Bowie or Mearns intended to write. Yet when you pair their efforts up, what you get is a whole greater than the sum of its parts. I'd like to know it's meaning.A Poetic Narrative in Two Movements.

First Movement: Antigonish: by Williams Hughes Mearns."Yesterday, upon the stair,

I met a man who wasn't there

He wasn't there again today

I wish, I wish he'd go away...

"When I came home last night at three

The man was waiting there for me

But when I looked around the hall

I couldn't see him there at all!

Go away, go away, don't you come back any more!

Go away, go away, and please don't slam the door.

"Last night I saw upon the stair

A little man who wasn't there

He wasn't there again today

Oh, how I wish he'd go away (web)"

Second Movement:

Since the focus of this article isn't on just two two sets of verses, and instead on what happens if you combine them into one, it also means having to look at two sources of background information. This is pretty much the only way to make sense of the subjects these poems discuss and bring up when placed together. Since the life and career of Ziggy Stardust is pretty much a worldwide phenomenon, the good news is it's possible to talk about Bowie's contributions without having to dredge up a lot of long, forgotten history. It's possible to talk about his efforts here in almost general terms, because that's the sort of luxury that a global fame such as his can allow fans and critics in terms of background knowledge. You can talk about the contents of most of his songs and almost everybody knows exactly what you mean. Even if they end up disagreeing with your final verdict on the matter. Call it the benefits of shared knowledge on a subject. Which is to say that everyone remembers David Bowie. Who on Earth is the name known as William Hughes Mearns by comparison? That right there is the catch. The more the shared knowledge of a subject, the less the need for background information.

This is the benefit enjoyed by someone who remains one of the greatest rock n' roll musicians of all time. The same can't be said for a now obscure English teacher who used to have a second career as an all but forgotten poet. In fact, while a search through the database reveals that Hughes Mearns wrote and published five volumes of poetry (one of which bears the intriguing title of Nights Goblins), along with two ground-breaking works of academic study which went on to help pioneer the modern creative writing programs in universities everywhere, there is surprisingly little information about this character to go by. To give an example of what I mean, I tried entering Mearns' name along with the title of the aforementioned "Goblin" text into the search engine. The Internet doesn't seem to have a clue who I'm talking about. If I type in the author's name, along with the title of his most remembered poem, Antigonish, then I'm given a respectable enough harvest of commentary to work with. Though none of it goes quite as far as perhaps it should. It goes without saying that none of it gives me anything a critic might need in order to deliver a complete biography of the poet scholar himself. I suppose the whole thing can stand as an object lesson in what happens when you forget a great deal of the past.

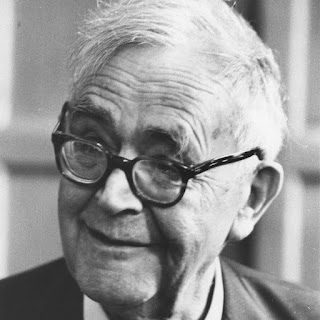

Here are the basic facts about Mearns and the one work everyone doesn't remember him by. His birth place was Philadelphia in the year 1875. His parents were James and Leila Mearns. Their son went on to marry a Miss Mabel Fagley later on in the year 1904. They had a daughter named Emma in 1907. While her father passed away in 1965, Emma managed to hang in there all the way to 2006. If you're looking for more on the basic contours of Mearns' life, then the real sad punchline is this. I just gave it to ya. I can always throw in a flock of seagulls if you want, but that's it. This seems to be about as far as anyone has ever enquired into the writer's personal life. As a result, Hughes Mearns could almost be thought of as a man who wasn't there in his own right. The one bit of biographical trivia that sticks out like a beacon on a foggy night concerns something I managed to learn about the author's academic career. From what I can tell, Mearns seems to have been something of a disciple of the philosopher John Dewey. He was an educational theorist who helped pioneer the first modern methods for teaching students in schools. If I'm being honest, almost everything I've found out about Dewey is admirable.

He left behind a greater paper trail and legacy than Mearns ever did, and so while it might not be much, it seems like the only way to get a handle on one half of the two artists under discussion here is to see if we can get to know the pupil by studying the work and thought of the teacher. Therefore when it comes to the philosophy and work of John Dewey I'm faced with the story of someone who could have been a great man. His life reads like one of those classic American sagas where the protagonist soon realizes his has the promise in him to do great things, only for him to suffer as the result of one, overlooked, fatal flaw. It'd be a mistake to take away Dewey's achievements. He not only established the modern school system, he also was a tireless champion of education for all, especially the working classes. He hit upon the obvious yet always overlooked insight that knowledge is power, and the more there is of it in any country founded on so much as a shred of Democratic principles, the better the odds of the people being able to live up to that promise. All of this has to be counted as a series of feathers in the cap. The kind of medals you can display with pride. So here is what's wrong with his equation.

The nature of Dewey's fatal flaw as a thinker is twofold. In a way, it all goes back to the maxim that knowledge is power. What the teacher didn't seem to factor in all that well was an old saying of the French political thinker, Montesquieu. "Power, exercised without foresight, is power lost". This applies all too well in the realm of knowledge, where, as Clint Eastwood once observed, "Sometimes a man's life can depend on a simple scrap of information". The way Dewey failed to take all this into account was in how he conceived of knowledge itself. The thought undergirding all his efforts at educational reform were a concoction of plain commonsense mixed together with a strange element of carelessness. So far as the goal was providing an education so that every student could potentially be a functioning member of a Democratic society, so good. It was in Dewey's ability to carry that necessary goal forward where his failings as a thinker sort of became apparent on two levels. The first was the philosophy that undergirded his desire to better the American School system. The second was how this reckless devotion to an otherwise admirable ideal somehow made him overlook the vital human element necessary to make it work. Dewey approached education through the lens of an outlook known as Rational Empiricism (web). It was an outgrowth of the Pragmatist movement in philosophy, and was also sort of the closest thing the professor ever had for a guiding light in terms of outlook and action. He let it determine his approach to how education should be shaped and went on from there.

The main problem with Dewey's method never lied in his goals, so much as the pitfalls that his choice of educational-philosophic method caused him to overlook. When I say Dewey was empirical in his outlook it means it shaped his approach to drawing up a workable school curriculum. His focus was always centered on quantifiable results. His belief was that only a pedagogy centered in scientific rigor. Now, to be fair, perhaps this is the sort of thing that wouldn't be so much of a problem in and of itself if we approach it using today's standards. The trouble both with and for Dewey was that here's the part where this progressive thinker still betrays himself as something of a man of his times. Rather than the more careful, cautious and considering methodology of the modern academy, Dewey's philosophy of education suffered from being limited in its outlook to the kind strict, one-dimensional practices of what passed for science in the 19th century. This is not to belittle the genuine advances made back in the day. We always stand on the shoulders of giants, in one way or another. The trick with science, however, is that its always in its nature to advance with better discoveries about nature and life.

To say that we've made leaps and bounds in fields such as chemistry and pharmacology in ways that couldn't even be dreamt of in Dewey's time is sort of the crux here. In particular, Dewey's outlook just wasn't expansive enough to make him aware of the study of other cultures as a legitimate form of enquiry. To give an example close to home, Dewey never bothers to ask about how the living experiences of both African and Native Americans can impact the way we teach kids their own history. Nor did he ever expand his definitions of concepts like culture and art in a way that would make room for modes of self-expression such as the Harlem Renaissance or how the social guidelines of the first Nations were eventually adapted and modified into the U.S. Constitution. Indeed, odds are even if you had told Dewey about that last piece of observable history, it is just possible he might have scoffed at what are now recognized as facts that can sometimes even factor into how we conduct our scientific research. In other words, it is possible for Dewey to be guilty of two failings that also manage to cover a multitude of shortcomings. He might have been able to tell you that it was the Arabic world that gave us our modern concept of counting numbers. Yet he might not have recognized the significance of say, how the ancient star charts of Alaska's tribal culture helped forward the study of Astronomy. Nor could he have told you what it was about their culture that made the sky so special to them.

It's when you notice all these various blank spots on Dewey's otherwise impressive map that you begin to see how we've been able to surpass him over the years. In other words, he's more of a better place to come from than to go back to. A lot of it is because of what he left out, or forgot to put into his theory of education. By thinking that the limited horizons of 19th century science would be able to cover every new discovery for all time, Dewey sort of helped lock himself out of the very future he wanted to help build for the Nation. It was because his philosophy never quite allowed him to see the whole picture of life as it is that he's sort of been eclipsed by the passage of years. When it comes to one of Dewey's disciples, like Hughes Mearns, the picture might be said to take on a bit of an added extra dimension, yet it still seems to have remained the same. In her own analysis of Antigonish, poetry critic Karen Ahlstrom was able to discover a further bit of trivia about Mearns list that might just provide us with the key information that can help us gain a grip on the one poetic effort he is still remembered by.

She writes that Mearns "dabbled in child psychology, especially as it relates to creativity. He pretty much invented "creative writing" as it's taught in schools. He thought that kids were naturally creative and eloquent, and they just needed to be shown how to let the natural poetry of their language come out as they put their thoughts down on paper. He said, "Poetry is an outward expression of instinctive insight that must be summoned from the vasty deep of our mysterious selves. Therefore, it cannot be taught; indeed, it cannot even be summoned; it can only be permitted." (quoted in Creative Writing And The New Humanities By Paul Dawson) He also talked about writing as a "transfer of experience" from writer to reader. He sounds like a fascinating person, and I'm surprised I didn't hear about him in my Education classes at college (web)". It's the poet's insight about artist's having a hidden, mysterious self that may provide an answer to the half-spoken riddle of the poem's meaning. While the addition of Bowie's lyrics can help excavate the significance of this popular sonnet a bit further as we go on.

Let's start with Mearns' idea that all art is the product of the artist's "mysterious self". In the strictest sense, this outlook is nothing new. In fact, all Mearns seems to be doing here is re-expressing a very familiar concept, one that can trace its lineage all the way back to Plato and the Classical Greek idea of the artist as beholden to a Muse unknown, a fiery inspiration willing to visit those whom it chooses to bless with or seize in a Inspiration. Plato in fact likened the experience to being gripped by kind of poetic rage. One that was necessary for the content of the Art to receive as close to its true and proper expression as possible. In other words, all that Mearns did was to hit upon the same idea that the Swiss psychologist Carl Jung had discovered a few years prior to him. Namely that the Imagination seems to be this autonomous property and function of the unconscious mind. Something of a paradox in that it is as natural as the heart or lungs, and yet its proper function grants it an extra level of value in that it seems to be purely mental in its nature and origins. It's this strange autonomy that gives the Imagination its sense of mysterious power. It also explains why so many writers describe the experience of storytelling as a work of discovery, or that the characters take on a life of their own.

If the Imagination is ultimately an unconscious, autonomous function, then perhaps there is a sense in which it can be said to form a larger part or aspect of life in which all human beings have a share, and yet which we can never quite control. Here's what all this seems to mean in terms of Mearns and his poem. The writer's thinking on the matter of Inspiration owes a lot more to Jung and earlier writers like Plato or Coleridge. At the same time, recall that John Dewey was his mentor. This gives us a portrait of the artist's mind as a strange kind of mental duplex. A house with an extra dimension to it that the inhabitant shows a kind of awareness of, and perhaps even places a certain amount of value in. The big question then becomes how much did Mearns value the Imagination on its own terms, and to what extent did Dewey's more limited theories of science and creativity influence the way the poet interacted with his own Muse? The best answer I can find for that is to say that in Mearns' case, it all seems to have come down a matter of divided loyalties. In other words, there was a part of Mearns mind (perhaps always somewhat half submerged) which recognized the value of Inspiration in the more expansive ways that scientists like Jung spoke of it. At the same time, most of his learning came from the mind of Dewey.

As noted above, it remains possible to speak of gaps and and shortcomings in the Pragmatic educator's philosophy. It is just possible that the same pitfalls of the teacher also applied to his student. Mearns seems to have gotten a bit farther in his thinking on the nature of the human mind than his old college professor, yet in terms of any greater understanding on this subject it always seems that Jung was to precede the both of them, while also always managing to remain more than a few steps ahead in terms of critical insight. It never seems to have occurred to either Dewey or Mearns, for instance, that a close and careful study of mythology could lead one in time to a more humanistic and expansive understanding of other world cultures, thus fostering a greater sense connectivity between human beings. The perfect irony incapsulated in this insight is that this is more or less part and parcel of the precise goal toward they had been aiming at all along. The fact that neither educator ever quite got that far might just count as one of the great unsung tragedies of 20th century thought.

2. The Singer and the Song.

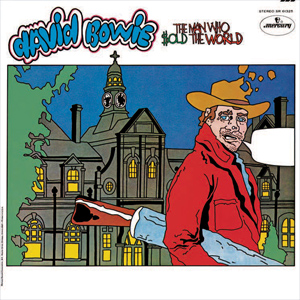

This leaves us with just two more elements to discuss. One of them is Bowie's contribution to this this article in the form of the backstory on how he came to write The Man Who Sold the World. Along with the inspiration that led Hughes Mearns to create the Antigonish poem as we now know it. In terms of the musical portion of our program, here's what can be found out about the rock n roll half of this review. To start with, it's now considered one of Ziggy's greatest works, and it seems like that's a good judgment call. Part of it seems down to the fact that in this track we've got Bowie finding that near perfect middle ground between the mainstream sensibilities of the Radio Top 10 Singles chart and the artist's commitment to his own unique musical vision. He's able to bring the masses in without ever having sacrifice the all the elements that make his artistry work. The funny thing to learn is that this particular song had what you might call a slow burn reputation to start with. It wasn't all that big a hit upon its initial release, in fact. The Man Who Sold the World came out as part of an album of the same title. When it first the shelves, however, most listeners, critics, and even Bowie's fans appeared to consider it just one more deep cut among many. No one ever treated it as anything all that special.

At least this didn't happen right away. Perhaps the most amusing thing that ever happened to a Bowie song is that it's started to gain a reputation of its own when it was first covered by another artist. This in itself isn't so unusual. It's just that when you hear that someone covered one of Ziggy's songs, you think it has to have been done by any one of the other musical acts out there that were on the kind of wavelengths that were similar, if not identical to Bowie's. The logic here is that if anyone is going to cover one of the tracks for the Band Leader from Mars, then it ought to be one of those avant-garde prog rock type bands like Genesis or Black Sabbath. Or else singers with the kind of image and approach that's able to match that of Bowie's in some way. Guys like Iggy Pop or Lou Reed would have been a good fit in this case. Instead, you want to know which artist first set The Man Who Sold the World on its path to being a classic track? Her stage name was Lulu. That's all, just Lulu. Let me put it this way. It's more than easy to imagine the number of logic responses such information is going to generate. Younger listeners out there don't have much choice expect to ask who on Earth am I talking about. And am I sure I didn't just make that name up? All the die-hard Martian Spider fans out there meanwhile are either begging me to say it's not true, or else cringing at the memory of it.

To which, all I can do is assure you that it's true. It happened. The song's initial reception was so cool that it got to where Bowie was willing to give it away as a gift for an actual mainstream artist of the time. The funny thing is how it was this choice which led to the song gaining its first bit of public notoriety. It wasn't much, in pop culture terms it almost reads like a blip on the radar now. However, back then it seems a flash in the pan could go a lot further. Ziggy's decision to give the song away was the first time anyone took notice of it, and for the first time people began to take it seriously. If this had all happened today of course, if Bowie were still alive and released this song as is in the current era, it would have become a viral sensation within the span of 24 to 48 hours, and the Spider King would have ruled the charts for quite a while. Since this was back in the analog days, however, it meant the song's reputation still had a way to go. It wasn't until the band Nirvana decided to perform their own cover of Sold for the now iconic MTV Unplugged series of concert specials that the song was able to gain the kind of mainstream fame status that it still enjoys to this day. The only regret Bowie seemed to have about it is that people would come up to him saying he did a very good Nirvana cover. I'm pretty sure its easy to imagine that sort of polite consternation the singer would always feel in such moments.

As for how the song came to be made, "Chris O'Leary writes that Bowie wrote the lyrics in the reception area of the studio while (bassist Tony) Visconti waited at the mixing console. Once he finished, he quickly recorded his vocal, Visconti added a "flange" effect and mixed the track in a few hours, sending the tapes to the label later that night. Bowie's last-minute addition frustrated Visconti, who recalled in 1977: "This was the beginning of [Bowie's] new style of writing – 'I can't be bothered until I have to'. When it was finished, on the last day of the last mix, I remember telling David, 'I've had it, I can't work like this anymore – I'm through...David was very disappointed." This frustration was mostly due in part to his dissatisfaction with the recording sessions: he was mostly in charge of budget and production, as well as maintaining Bowie's interest in the project. Bowie later told BBC Radio 1's Stuart Grundy in 1976: "It was a nightmare, that album. I hated the actual process of making it (web)".

As for what the singer himself thought of the meaning of the song, Bowie went on record as stating "I guess I wrote it because there was a part of myself that I was looking for … that song for me always exemplified kind of how you feel when you're young, when you know there's a piece of yourself that you haven't really put together yet – you have this great searching, this great need to find out who you really are (ibid)". I think that might be the one statement that helps unite the two works under discussion here. I'll get to what I mean by that in the final section of this review. For now, all that remains to be talked about in terms of the backstory for this double analysis is the story of the supposed haunting that inspired Hughes Mearns to write his almost childlike lyrical composition in the first place.

3. The Forgotten Ghost.

Is there any narrative more perennial than the Ghost Story? Offhand, I can think of just one other genre that might outpace it in terms of age, and that is the prototypical Fairy Tale, or Fantasy. It makes sense considering the truth is that the former always seems to have been an outgrowth from the latter. Horror Fiction is all you get when the narration chooses to focus in on the ghastly haunts hiding in the shadows, the trolls lurking under the bridge, and the various assortments of evils spirits over the exploits of the wise and noble elves and dwarves. This is a fact that seems to have been understood on an instinctive level even by authors such as Edmund Spenser. All it took was for someone with the right mindset, in this case guys like Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Poe, to sharpen the nature of that incipient Gothic narrative focus. It should come as no surprise then to discover the Ghost Story is one those genres that can trace its lineage as far back as Ancient Egypt and Greece. In his non-fiction study Danse Macabre, Stephen King claims that the haunting figure known as "the Ghost is an archetype...which spread across too broad an area to be limited to a single novel, no matter how great.

"The archetype of the Ghost is, after all, the Mississippi of supernatural fiction (51)". That seems to be a correct enough assessment as far as this particular amorphous character is concerned. My thinking is if you've managed to survive the passing of the Bronze, Classical, Middle, and Early Modern Ages up to the present day, then there's got to be something said for the artistic quality of an archetype with such an impressive level of staying power. A lot of that comes from the way the Ghost Story is able to tap into one of man's most primal of stock responses: fear. It's something that Hughes Mearns (again, just like Spenser) seems able to grasp at an unconscious level. I've read articles that describe Antigonish as a form of children's nursery rhyme. All I can say is if that's the case, then it's one of that takes after a much older form of the Gothic Fairy Story tradition. This is a poem that seems to have a good idea of its ancestry. Its diction and rhyme scheme are simplistic. It's easy for a young, developing mind to grasp and get ahold of at a fairly quick pace. The poet's verse lends itself naturally to mnemonics.

With these facts in mind, its easy enough to understand why people might categorize this bit of doggerel as meant for the pre-teen (maybe even pre-school) Young Adult demographic. It also explains why a children's author and like Jack Prelutsky saw fit to include it in his own anthology of verse edited for young readers. It even makes sense to presume that this simple seeming lyric has been used by, say, Kindergarten educators across the country to help their growing charges begin the always unfinished task of honing their reading skills. Antigonish is the kind of work that lends itself to the nursery. At the same time, this is a poem with teeth. It's words are able to carry this immediate sense of controlled shock followed by just the right slow-building sense of dread, menace, and even incipient paranoia. It's the kind of thing where, once you've read the first set of rhyme couplets, the hairs on the back of your neck can't help turning up, and you're left with the uncomfortable sense that, just maybe, you're being watched. The worst part is that some primitive basement level is of your mind is busy asking all sorts of questions. "What if there is someone, or something always peering over the shoulder"? "If I can't see or touch this "Watcher", is that thing still capable of doing me harm"? Here's perhaps the worst response a poem can call up in your mind. "How bad would it be if I saw what It looks like"?

In other words, Mearns is able to collapse you back into the same state of childlike terror with the same skills as that of M.R. James or Guy de Maupassant. It leaves the kind of dramatic effect that makes you afraid to walk through a dark hallway, or be overcome with the desire to place you back against the wall as you very carefully inch your way down the stairs, even if there's (nothing?) there. It's then as you've almost made it down without incident that you realize with a shock of terror you didn't expect that your path down takes you right across a window looking onto the sane world outside. Suppose, you think to yourself, once I get to that window. What if a pair of invisible (claws) hands grabs me by the throat and shoves me not out but into the window, so that the glass...I think the fact a supposed "children's" rhyme can illicit these kinds of responses, or generate such ghoulish thoughts in the minds of readers is the best testament we have to Mearns' ability for tapping into our fears of the unseen and unknown. It also telegraphs that a work like this can perhaps never be confined to just one single age demographic.

The question author's like him get asked all the time, however, is, "Where on Earth do you even get ideas like that"? It's a question a lot of Horror authors seem to struggle with. King's go-to response basically amounts to something like, "Folks, you might as well ask me why the sky is blue on a normal day". In other words, most of them are just as clueless as the reader. In Mearns' case, the very title of his poetic effort points to its exact place of origin. It all seems to have come from reports of a haunting way up in the otherwise overlooked county nestled within Canada's Nova Scotia. On a family farm located in the county of Antigonish, there were reports of poltergeist activity going around. A list of the so-called paranormal phenomena covers the usual ground. Doors would slam or open of their own seeming accord. There were unexplained noises. Banging coming from pipes and the walls. The feeling of being watched or observed from some unseen observer always just out of sight. The standout feature of this poltergeist is that a lot of fires would erupt at unexpected intervals, whether in the house, the barn, or out in the fields among the lives stock. In other words, the classic haunted house scenario.

My own research into the incident leads me to the conviction that the ultimate source is traceable to the antics of a troubled mind known as Mary Ellen MacDonald. She was the adopted daughter of Alexander and Mary MacDonald, the couple who owned the Antigonish farm. When all the evidence is gathered, the truth inside the legend of the Antigonish poltergeist reveals an angry young girl who either felt or genuinely was unloved by her adoptive guardians. As a result, what we've got on our hands is one of the most familiar tragic patterns in life. A child is raised in hostile surroundings. It's here that the experience of neglect and abuse will lead not to the inevitable, just logical enough conclusion of the child lashing out in whatever way she can. The motivation here is to "get even" or "get back" at the people dishing out all the abuse. In fact, if you go back and look not just at Mary Ellen, but a lot of historical records out there, you'd be surprised to discover just how much the desire for revenge acts as a motivating factor in a lot of the most famous moments in history. In Mary Ellen's case, her strategy involved making the kind of ruckus that would guarantee the least likelihood of being caught and then physically abused as punishment. This meant pretending to be a ghost haunting the household.

I guess the best way to describe the result of this strategy and the unexpected and therefore complicating fame that Mary Ellen's antics brought her is to say that here we have the closest perhaps anyone has ever come towards being a Stephen King protagonist in real life. With the case of the unwanted, and cast out Mary Ellen MacDonald, we see the makings of fictional creations like Carrie White brought to living, breathing, embryonic reality. At the same time, Mary Ellen's ultimate fate stands as a good example of the difference between fact and fiction. Rather than any dramatic denouement, the orphan's antic's were eventually discovered, and after spending a great deal of time in and out of reformatories, the abused woman known as Mary Ellen nee MacDonald, ended her life as a patient confined to a mental asylum until almost the last years of her life.

There's a sort of bitter irony in the way her life tragedy helped inspire Mearns' Antigonish. The title of the poem itself is a dead giveaway that it's based on the troubled girl's life. The county of the same name in Nova Scotia is the location where Ellen practiced the art of being a ghost. I don't think she ever meant to get her name in the paper, yet it's what happened. It's also how Mearns came to learn about her exploits, at least, in the first place. There is one point on which all I can offer is speculation, at best. There's an item in Mearns biography which states as a matter of fact that he once utilized the Antigonish poem as part of a larger story. It was either recited or else re-created as part of the production of a stage play Mearns wrote and produced under the title of Psycho-ed. A mercurial part of my mind thinks all you need to do is to add the phrase National Lampoon's to the header and you've got a pretty good idea for a raunchy sex comedy sequel to Animal House. That at least gives the reader some idea of what type of story Mearns was writing. If there's any truth to this speculation, then it makes the poet something of a forgotten pioneer in the format of subversive college comedy.

This could have been a laudable feather in the cap for him if it weren't for one nagging question. How much did Mearns know about Mary Ellen MacDonald? The reason I ask might sound stupid. It's just that the title of his stage script is a play on the academic word co-ed. In other words, a college open to both men and women. They would be put in separate dorms, yet the idea of equality of education for both sexes was operative in theory, anyway. It's just the fact that the play's title implies the presence of a woman, either as lead, among the main cast, or else as a guiding factor in the plot that gives me pause, and makes me wonder how much Mearns knew about MacDonald. The unspoken concern here is of course the nagging fear that we could be dealing with the case of an author taking advantage of a real woman's misfortunes, and then shamelessly capitalizing off of it for his own selfish reasons. Now to be fair, I have no proof of any of this. I merely put it out there due a sense of moral caution. If it were ever provable that Mearns knew about Mary Ellen, and that her life story inspired his play, then it remains to be seen whether or not his comedy can be said to treat her with the respect she's due.

It would therefore be very interesting to get a copy of Mearns playscript put online. That way everyone could judge for themselves whether or not we've got a case of the author as exploiter, or else something more fitting to the memory of Mary Ellen Macdonald. The kind of story, in other words, that might count as a literary precursor to novel's like Shirley Jackson's Hangsaman, except this time, it's all told in a more comedic, happy ending sort of vein. At the very least, it's a bit of food for further thought.

Conclusion: Two Poetic Aspects of a Greater Theme.

So now that all the pieces of the puzzle (a poem, a song, and all the various assorted elements that go together to create each artwork, or that both share in a manner of thematic overlap) have been assembled on the table, what happens if we try to put them altogether? What kind of picture do we get if you place the contents of Mearns' poem and Bowie's song into the same blender? Well, the final result might be termed as an over-arching thematic idea, or literary-artistic concept. I think the best possible description of this idea can be found by something Stephen King once wrote about in Danse Macabre. He was talking about the contents of a novel that has more or less no connection with the two works under discussion here, yet one conclusion that King arrives at seems to be the heart or core of Bowie and Mearns' efforts. There's a scene that King describes where a man wakes up in the night and sees this very strange girl he's just met at a window, staring out into the night. "He asks her if anything is wrong, and she replies. At first he persuades himself that her reply has been "I saw a ghost." A later truth forces him to admit she may have said "I am ghost." A final act of memory retrieval convinces him that she has said something far more telling: "You are a ghost."

If you had to ask me what main connecting threads unites Antigonish and The Man Who Sold the World, then it would have to be this obtuse yet somehow evocative idea. Perhaps we can start to get a better sense of the logic behind that statement if we place the verses of the two poetical works side by side.

"Yesterday, upon the stair,I met a man who wasn't there!

He wasn't there again today,

I wish, I wish he'd go away"!

So what does any of that tell us on a real world thematic level? Well, a good place to start explaining it in life-size terms is to look again at the contents of Bowie's own song. "The lyrics are noted as very cryptic and evocative; in (music critic Peter) Doggett's words, "begging but defying interpretation." Like most of his work during this period, Bowie frequently avoided giving a direct interpretation of the lyrics; he later remarked that he felt it was unfair to give it to Lulu in 1973 because it dealt with the "devils and angels" within himself (she later confessed she "had no idea what it meant"). Bowie once stated that the song was a sequel to "Space Oddity" which, in Doggett's words, is "an explanation designed to distract rather than enlighten", quoting the lyrics "Who knows? Not me". The song's narrator has an encounter with a kind of doppelgänger, as suggested in the second chorus where "I never lost control" is replaced with "We never lost control". Beyond this, the episode is unexplained: as James E. Perone wrote, Bowie encounters the title character, but it is not clear just what the phrase means, or exactly who this man is...The main thing that the song does is to paint – however elusively – the title character as another example of the societal outcasts who populate the album.

It's a case of the artists or the subject learning to deal with important things that have been left out of their lives. It's' Hughes Mearns trying to discover the neglected, greater aspects of life and the self than that dreamt of in Dewey's philosophy. It's Bowie ruminating on fame, time, and the kind of childhood outlook that you're always in danger of losing along the way if you're not careful. It's also perhaps Mary Ellen MacDonald in search for her missing sanity, and the girl she used to be. All of these examples point to the idea of the subject of the poem either meeting up with or else looking for their lost self. Those needful aspects of the personality that the human can't seem to go without and not risk the threat of insanity. Looked at from this perspective, what is that archetype of the Ghost but a symbol of things past, lost chances, and the possibility of losing one's mind? Now to be fair, it's always possible for the archetype to symbolize a greater number of roles and meanings than just the ones outlined above. However, these are the most famous performances that the phantom revenant is known for, and that it keeps coming back to. The idea of lost aspects, chances, and guilty pasts all seem to be ideas the archetype was more or less made to express and dramatize. This is something that writers like Shirley Jackson knew all to well, and it manifests in Mearns' poem, and in the lyrics of Bowie's song.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment