The trouble here, however, is threefold. For starters, it's true that attentive fans have been able to spot a legitimate piece of literary allusion, and borrowing. King really did turn to the work of another author in order to come up with concepts like the Drawing Doors, the Tower Rose, and perhaps even something of the general background of that series main protagonist. The second issue is where the kick in the teeth comes from. Even if its true that King used someone else's words to construct his own story, the ironic fact remains that most of his readers don't really have any clue where the quote comes from, or who wrote it. That brings us to the final challenge. The name of the author who originated those words, and the work of fiction that they all appeared from. Whoever it was, he must have been of some importance. I mean, it obviously impressed King enough to the point where he just felt like he had to use a line from it as a piece of actual, literary world-building. What does that tell us?

The answer is very little to go on, as it turns out. The reason why is simple of enough. How many out there are willing to go the lengths necessary find out where that quote came from, and who its author was? Who of us out there is willing to be enough of a bookworm to the point of having something like a genuine curiosity about the whole thing? My guess is that the best possible answer to this question would have to be precious few. There's never been anything like a functioning, workable culture that encourages that level of literacy as something like a genuine asset. Luckily, I'm the sort of time-waster who doesn't mind a deep dive into the minutiae of pop-culture, so I thought I'd go ahead and go out on a limb, and have a good old-fashioned book hunt. The result was that I found what might be called the answer. Though, in order to tell it, I'm afraid I'll have to go into a bit of literary history.The Story. The history of literature itself is an ironic one. On the one hand, some works and writers are able to make household names for themselves. Everyone knows about Dickens and his Christmas Carol, for instance. And most people are familiar with the Shakespearean phrase, "To be or not to be". And even the majority still seems to have an idea of the play in which that ancient question can be found. The trouble is that even old Bill, from Stratford, England can't seem to overcome this curious selectivity that audiences have about what they do and don't choose to commit to memory. We know about Hamlet, and possibly Romeo and Juliet. Now what else did the old play actor write? Who here can list a number of other scripts that Shakespeare had to his name? The results might surprise you. It's possible that a few other samples will be able to crop up after some time. It's just that you really had to think it over and put your brain to work, before any of those other titles began to crop up from whatever aether it is they go back to when the world moves on. It's the same all over, where ever it is you happen to turn.

The truth is that writers like Dickens and Shakespeare are lucky their careers have managed to last even this far. I guess it does say something pretty favorable for the level of their respective talents. If they weren't all that good, would we even be able recall such an illustrious figure as Old Marley's Ghost? The likeliest answer is probably not. However, just as it says something about Boz and Bill as writers, I think it also casts a light on the history of the audience as well. The worst part is I'm unable to tell whether it amounts to a good or a bad thing. If you know about Shakespeare, then what about Louisa May Alcott? Who was Charlotte Bronte, or Ken Kesey? Does anyone even know about Emily Dickenson, or that a writer by the name of John Buchan once existed? Who was Shirley Jackson?

If you're having a difficult time recalling most of those names, then it probably says a lot about what kind of premium we as a species tend to place on even the best examples of writing. It's like that old Pete Townshend lyric has it. "Words flow, people forget". It's the forgetting that bugs me the most, I guess. I've just never seen anything healthy about it, if I'm being honest. What it tells me is that this lack of literary awareness is the kind of mistake that might be able to chalk up a pretty high price-tag, if we're not careful someday. Even if we do manage to make ourselves a great deal more literate, there remains an entire cadre of untold millions out there who still might never get as much credit as they deserve. I'm not just talking about the Big Names here, anymore. I'm thinking of the sort of folks who exist behind the fame of authors like Jane Austen or Mervyn Peake. We're now venturing into the realm of what Billy Wilder once referred to as "All the little people, out there in the dark".

I'm talking now about the assistance that even guys like Dickens needed if he wanted his words to see the light of day, in their best possible formatting and style. The thing to keep in mind now is that while he was the main engine behind his own fame, I doubt there's any way that Boz could have amounted to more than just a sketch artist without the help of trustworthy editors, people who knew books, how they were made, shaped, or created, as well as how to shepherd them from that first, all-important, initial idea, and carry it on from there to its final appearance on the printed page. That's the kind of help that even Shakespeare had to rely on in order to help cement his fame. Even giants can sometimes stand on the shoulders of those greater than themselves. All well and good. Now, who edited Shakespeare?Does anyone even recall who that might have been? What about Jane Austen? Who helped her get her voice heard? That's to say nothing of editors for writers like Ralph Ellison, or whoever was willing to take a chance on Jamaica Kincaid. A guy named Chuck Verill passed away the other day or so ago. The only person who felt obliged to bring it to anyone's notice was Stephen King. Why is that, do you suppose? Are you starting to see what I mean? For all the writers who makes a name for themselves, there are a ton of trench toilers working behind the scenes, and whose efforts will often remain nameless, even when many of the writers out their are aware of all the help they've received, and then try to help give these hands without names a voice of their own. The effort is valiant, and the audience still doesn't listen perhaps as much as it should, if only as granting a secondary form on honor.

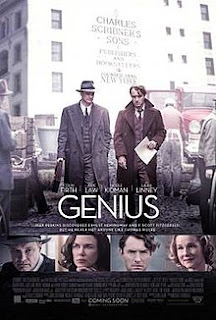

It's very rare for the editors of great writers to achieve anywhere near that same level of notoriety. Those that do can probably be counted on the fingers of a single hand. Nobody knows anything about a name like Maxwell Perkins (Colin Firth). That's what makes it all the more remarkable that some scribbling artists out there have been more than willing to make sure he doesn't vanish into obscurity. He was just some nothing kid from Plainfield, New Jersey. In fact, I don't think his parents ever saw anything like the potential for literature in their son's future. They had him streamlined for a career in economics, for goodness sake. Who on earth would want to bet their life security on a bunch of make-believe? Better a steady career in finance, something that would keep young Max well provided for. This all happened some time before the big Stock Market Crash of 29, if the dates are correct. Just in time for the great depression. Perkins seems to have managed to bypass a lot of it by skipping his assigned lessons, and finding something more productive, like wasting his time away in Harvard's English 101 classes.

That's were he met Charles Townsend Copeland. Remember how I said that behind every great writer was a great editor? Well, it seems like that's the sort of rule that stretches all the way up and down the chain of being. A better way to phrase it might be to say that behind every great editor there lies just the right academic mentor. One of those people who always seem to know a lot about everything to do with literature. That's what Copeland turned out to be for Perkins. In that sense, it was a bit like winning the luck of the draw. Copeland was one of those teachers of English who "knew books" inside and out. He didn't just make sure his students read their assigned texts, gave them a quiz or two on it, and then called it a day. He made sure his pupils knew the actual content, context, and literacy that informed each text he brought to their attention. Copeland was one of those types who are interested in the why of literature, and it was an enthusiasm he was able to pass on to Perkins. Maxwell was one of the more reticent individuals coughed up by life, and so he often kept his opinions close to the vest.What can't be denied, however, is that his time as a student learning under the careful guidance of Copeland was the main catalyst in his life. It's what more or less shook him awake, and made him realize it was possible to run away from the circus, in order to join real life. What Perkins seems to have gotten out of it all was a sense of literature's natural place in the grand scheme of things. It's what enabled him to believe that it was something as vital to human life as breathing or seeing, even if we never perform the latter function as well as we perhaps could, or should. Copeland was the one who helped Perkins see that a good book is just as vital to human sanity as much as a clear head. It was armed with this knowledge that young Max made a beeline straight for the world of words right after graduation. He got his professional start as a reporter for the New York Times, though his sights always remained firm and set on a career in one of the big publishing houses. This was back in an era when a simple, brick and mortar publishing firm could go a long way without the need for corporate paychecks.

It was a goal that Perkins stuck to with a tenacious hold, and he must have meant it. Because he soon managed to secure a job for himself as an advertising manager at Charles Scribner's Sons. The firm that is now known simply as Scribner's. In time, Max worked his way up to the top as one of the firms editors. This was the place where writers like Henry James and Edith Wharton were allowed to have their voices heard for the first time. It stands to reason that this is information that Perkins must have been familiar with, otherwise he probably wouldn't have single out Scribner's as the place in which to make a future for himself. When he first got started, however, his professional practices as an editor were somewhat unique. His main focus was often kept on the lookout for new and promising young talent. This meant Perkins took it upon himself to be the one who was willing to put himself through the necessary torture of reading through manuscripts submitted by green novices and neophytes.It can be one of the most rewarding and thankless tasks out there. There's supposed to be an old saying that writing is easy, life is hard. That's a bit of misstatement, in fact; on several levels. In the first place, it's impossible to know what anyone means when they use a word such as "life". As for literature, the real truth of the matter has always been that neither writing, nor reading for that matter, has ever been what one could describe as an "easy task". Stephen King once likened it to a nine-to-five job, such as bricklaying, or mechanical welding. On the whole, a long time of personal experience in this field leads me to believe he got that part right on the target. Even if the words are coming easy (and heaven help you on the days when they don't) the job of writing remains just that. It is a task to be accomplished. This is not to say that there is no such thing as a joy to be found in literary creation. Far from it. If that weren't the case, there'd be a lot less books to go around. It's just that literary composition is ever as much a chore as it is a calling. Another thing King got right, therefore, is when he called the task a matter of commitment. You either prove you're able to stick with it, or you don't.

That applies just as much to readers, as it does would-be professional word slingers. The irony is that reading well is just as much of an actual "Art" as the chore of literary inspiration itself. It's something that takes patience, and above all, a genuine ability to love the very medium of words on a page for what they are. It's one of those things that can be a natural inclination (I guess I'm lucky in that sense). Though for others, its yet another mountain to climb. It's as if learning to read well and enjoy a good book is one of those personal victories that can often be hard won, and Perkins seems to have been one of the all-time champs. This was especially true whenever he had one of those days where he got stuck reading the sort of amateur manuscript that was probably enough to make his brain want to tunnel its way out of his skull in a desperate effort to protect itself from the earth-bound version of Vogon poetry. Something tells me this might have been more of a general office rule, rather than any kind of exception. Theodore Sturgeon once opined that 99% of everything was absolute crap from start to finish. If those percentages are correct, then that meant just ten percent of anything that crawled onto Perkins desk was ever going to be the kind of work that would ever amount to much. It just seems to be an inescapable fact of the writing and reading life. Whether curse or karma, it just is.

Still, Perkins stuck with it out of a committed passion, and it's not like they were all duds. Sometimes, in fact, a text would land on his desk that sometimes went the extra mile, the one that means so much, and that all publishers try to keep an eye out for. One of these samples was called The Romantic Egoist. The title might have needed some work, yet the story contained in the pages was one of the first times that an amateur made Perkins sit up and take notice. He contacted this young author, a Minnesotan named F. Scott Fitzgerald (Guy Pearce), and after that first interview, followed by a few editing consultations, the result was the publication of This Side of Paradise. It marked Fitzgerald's publishing debut. It was also the first instance in the creation of the voice of Literary Modernism, a movement that would encompass Fitzgerald, Perkins, Gertrude Stein, T.S. Eliot, and John Steinbeck.There was also one other figure in this movement that Perkins seems to have helped accidentally usher into the publishing mainstream. In fact, it's this other writer who is sort of the latter half of the main focus here. Somewhere around 1928-29, another manuscript made its way onto Perkins' desk. It was a big, hulking damn thing, almost enough to serve as its own paper weight, or else maybe just a convenient door stopper. If what was inside wasn't worth the effort, then maybe that's just the use Max would have put it to. However, that's not what wound up happening. Instead, when Perkins turned to the very first page of a working title known as O Lost: A Story of the Buried Life, he read this:

“. . . a stone, a leaf, an unfound door; a stone, a leaf, a door. And of all the forgotten faces.

"Naked

and alone we came into exile. In her dark womb we did not know our

mother's face; from the prison of her flesh have we come into the

unspeakable and incommunicable prison of this earth. Which of us

has known his brother? Which of us has looked into his father's heart?

Which of us has not remained forever prison-pent? Which of us is not

forever a stranger and alone?

"O waste of lost, in the hot mazes,

lost, among bright stars on this weary, unbright cinder, lost!

Remembering speechlessly we seek the great forgotten language, the lost

lane-end into heaven, a stone, a leaf, an unfound door. Where? When? O lost, and by the wind grieved, ghost, come back again (1)".

It became even more clear as Perkins took the manuscript of O Lost home with him. It got his attention enough to the point where he spent most of the night up leafing through the pages. By the time he got back to his office the next morning, he was more or less sold, and ready to contact that author. When they finally met in person, the youngster seemed to be just as full of the same vitality as his own book. You could tell that Thomas Wolfe and his novel were almost one and the same. That was not much of a surprise, as he confirmed Perkins' suspicions that the novel's hero, Eugene Gant, was pretty much an autobiographical portrait of Wolfe himself at that age. In a sense, Tom, admitted, the novel was sort of everything he'd just left behind.

Perkins was therefore dealing with something of cross between a roman a clef and a proper novel. The funny thing to notice, as he told Wolfe, was just this. It was good. It needed a few editorials, there may even have to be a word cut or two, here and there. If there's one thing the book could do with, it was a healthy lack of excess verbiage. Also, perhaps something should be done about the title. That said, Perkins admitted to Wolfe that he had a genuinely good piece of work in his hand, and the young man was to be congratulated. A few redactions and editorial meetings later, and it wasn't long before a new book, Look Homeward, Angel, had hit the stands. It didn't take long for it to become a darling of the critics, and something of a bible for a lot of the aspiring young writers out there. It also marked the start of one the most contentious, and productive times in the life and career of Maxwell Perkins.

Conclusion: A Film with an Identity Crisis.

If any of what I've written above sounds interesting, then I apologize. Apparently, I've written a better story than the one the film is able to give us. That was not my intention, let me assure you. I know that's what should have been the goal of the movie itself. That it fails to meet its own standards can be chalked up to a number of factors. The biggest issue all seems to come down a fundamental problem. No one quite knew how to handle the subject matter they had to work with. A lot of it is down to how they chose to handle their source material. The film's main focus is on the professional relationship between real life editor Max Perkins and the equally historical writer Thomas Wolfe. For whatever reason, the filmmakers decided that this was the correct route to lean into when it came to the choice of story material. Now, to be absolutely fair, this doesn't have to be looked at as one of those creative decisions which is inherently incorrect by nature. In fact, I almost want to argue that it could have worked. In the planning stages, for instance, it does at least sound as if they'd started out with something like the right approach. This is something that goes back to the way biopics are made.As I've said elsewhere, it really does look as if Hollywood is starting to get the right idea when it comes to making films based on the lives of real people. The best formula for this type of movie seems to be to shift the focus onto just one or two defining moments in the life of a famous personality. This allows the filmmakers to tell a relatively self-contained story, while also allowing the audience to get to know a real historical person, or subject in a way that somehow manages to be both familiar and intimate, without having to get weighed down by the demands of telling an entire life story that would just serve to come off as necessarily fragmented and distant. Tightening the focus of the story, on the other hand, allows the filmmaker to tell a piece of history in a way that comes off in a way that is more dramatically satisfying. It's a technique which Milos Forman realized well in Amadeus, and was later replicated to stunning, and in some cases downright surprising effect in films like Selma.

To their credit, the makers of Genius do start out on the right foot in this regard. They've decided not to tell a life story, but rather keep things centered on the clashing egos of a writer and his editor. Okay, then, so the setup is not that original, there's probably a ton of other examples of this trope out there. However, if the cards are played right, then we can at least get something like a cozy little personal drama out of the whole affair. It's even possible to go out on a limb and say that the opening to film looks promising enough. It starts with Firth's real life character as we open on Perkins going through the motions of his daily routine. We see him leave his house in the country as he does each morning to catch a train to his office in the Big Apple. The movie is wise enough to give Firth just enough space in these opening moments for him to help give us a sense of who Perkins is, and what life is like for him, at least as far as he can see it. He looks and acts like a combination of the quiet, retiring sort, combined with a sense of literacy and intelligence. This in itself amounts to a combination of character traits that result in an intriguing dichotomy. On the one hand, Perkins is an average, office working Joe Schlub.His basic situation is captured in almost perfect summation in an old car radio standard by the Vogues. The one the goes, "Up every morning just to keep a job. I gotta fight my way through the hustling mob. Sounds of the city pounding in my brain, while another day goes down the drain". What makes Perkins' case stand out from all the other commuters living the same story right beside him is the nature of his profession. He gets paid to read for a living. It's the sort of occupation that's always going to catch everyone else off guard. Compared to something like accounting, or construction work, there's this sense of rarity in the idea that anyone would ever want to bother about forking over the potential for hard earned income to some nobody just so they can get their nose stuck in a book. In a tactile oriented, hands-on society like ours, such an enterprise will always have to come off as a little strange. It's almost as if he's being paid to act like some sort of layabout. That's strike one against him.

The other thing that singles Perkins out from the rest of his fellow men is the same aforementioned sense of literacy, which in his case really does amount to a great deal of genuine intelligence. Firth gives us the sense of Perkins as someone who clearly loves his job. Yet he's also aware of just how much it can potentially alienate him from others. He's managed to place himself in a position that is ideal for what he wants. And yet it's precisely what his job entitles that, while it's wrong to say it places him on any sort of level above others, it does create this interesting sort of barrier between him and, say, those in the train around him. There's a good scene that illustrates this when Perkins finds himself forced to recite a line from Shakespeare on the same rail line a few scenes on. He's trying to school Wolfe in the proper art of a literature, and while he's doing this, he does get occasional suspicious glances from those around him. It's nothing hostile, just the note that something "off" has been introduced into an otherwise normal setting. I've no idea if this scene ever happened in real life.

This is where a book such as Look Homeward, Angel comes into play. In both the film and real life, it tells the story of a creative mind eventually escaping from the restrictive confines of a puritanical family situation. The main character is a natural writer who hears the siren call of the Muse, and the novel follows him as he spends the rest of the page count slowly, and painfully tearing himself away from a household that would do all in its power to stifle that urge. It's pretty standard stuff, in other words, and yet it can be done right when placed in the right hands. Wolfe seems to have done it right, for the most part. And yet it is this main idea of the clash between the artistic impulse and the mundane that seems to be something of a shared link between Wolfe and Perkins. It would therefore have made perfect artistic sense to try to find the right entry point into that idea, and explore it for all it was worth.

I just wish that's what they had done. Instead, it's like we're dealing with a film that has an identity crisis on its hands. What makes me say that is the way things start to fall apart right after what is essentially a very truncated first act. This is also the single portion of the film where anything interesting is going on. The main focus of this first segment all revolves around the manuscript that will become Look Homeward, Angel. The reason this section is the best out of the whole film is because of the way the novel itself is utilized as an initial driver of the story. It's what introduces Perkins and Wolfe to one another, and it clear that its overarching main theme of being true to oneself, and the clash of idealism versus conformity is a topic they both have in common. It's this sense of shared purpose which allows them to have a productive working partnership, and the more I think about it, it keeps growing ever more obvious that the making of Look Homeward, and its road to publication is what should have been the ultimate plot of the movie. It would have been an ideal situation in several ways.

In the first place, it allows the film to have a scenario that is basic enough for everyone to wrap their head around. This also helps frame the picture as a genuine success story. The truth of the matter is that the publication of Angel proved to be a breakout performance for Wolfe. Whatever personal ups and downs he might have suffered afterwards, his reputation as a Great Name was secured. This is the best possible arc that the movie should have focused on for its narrative. It would have given the viewers the kind of rags to riches narrative they could have easily gotten into. If it's the story of how an underdog makes good, then the majority of audiences are more likely to gravitate toward someone they can root for. It wouldn't have been all that difficult to rewrite the script to fit this scenario. There are even a number of possible ways this type of story could have been approached. You could, for instance, start out with Wolfe as he was in real life. He was a neophyte with a headful of bright ideas, and he was looking for some way to make it all pay off. Then you have Perkins as the mentor figure.The rough draft of Look Homeward, Angel could have served as the Rosebud maguffin that both kick starts the plot, as well as uniting writer and editor in a common enterprise. I pointed out earlier how the movie portrays Perkins as a literate man whose intelligence has still managed to set up this barrier between him and others. Wolfe is technically the first common man he's ever spoken to on a long, damn time. A lot of that is down to the fact that Wolfe is the kind of working schlub who can also speak up to Perkins' level. It's another thing that makes it easy to take on the O Lost manuscript as a prospective client for publication. What should be highlighted in this case is the way that the themes of that novel speak to Perkins' own situation. He's a man whose been there and done that. At the same time, an irony should be introduced. While the novel speaks to Perkins' situation, it does so from the perspective of a guy who, to all appearances, has managed to accomplish the goal that Wolfe currently has his sights set on. This means Perkins has seen the writing life from both sides.

It's what's given him a greater sense of perspective than Wolfe currently has about his chosen career path. As a result, the neophyte has a less mature grasp of things than the editor. What Perkins understands is that while he has achieved the goal he always thought he wanted, it's come at something of a price. This would have to be that aforementioned sense of alienation from those around him. It isn't the kind of thing he noticed all at once, and yet when the realization did hit him, it didn't take long to figure out where it came from. The truth is that somewhere along the way, Perkins either traded in the ideal of being a Man of Letters for an excuse to hide away from others, or else that was just always the real goal, and a literary calling was the best excuse he could find that would allow the editor to keep walling himself off from the world. Wolfe's manuscript is sort of the first wake up call he's had in a long while. It's all too easy for Perkins to recognize either who he was or could have been in the young writer. This is the overall subtext that should be made clear over the course of the story's action.

The main business of the plot, meanwhile, would focus on the ups and downs that Wolfe and Perkins go through in trying to make the future Angel text worthy for the public bookshelf. You could have scenes devoted to fights breaking out between Wolfe and his editor over what stays in and which parts have to be left out. These are the moments where a lot of old saws get their time in the spotlight. Wolfe is the uncompromising writer arguing for artistic integrity. Perkins, meanwhile, is stuck trying to get him to see that none of that has to be sacrificed, especially if all that's being cut out is the dross, etc. Sandwiched in between these main scenes would be sequences that split their time between Wolfe and Perkins in their separate private lives. We'd see Wolfe displaying a lot of the occasional self-sabotaging acts that would plague the real writer for a great deal of his life, and how the ghosts of his past still continue to haunt him. Perkins, meanwhile, would be shown trying to straighten things out with his own family, and its in these scenes where the character would be shown slowly coming toward his own self-realizations. This is what would allow Perkins to confront Wolfe about his own failings.It's also what helps Wolfe see how there's always a danger that he could betray his own principles as both an artist, and above all, a human being. The lesson both of them should come away with is something that Stephen King found out a long time ago. "Art is a support system for life, not the other way around". The film would therefore end on an upbeat note, with the camera lingering on a fresh, newly minted copy of Look Homeward, Angel now sitting in triumph on the shelf of a local bookstore. That, in essence, is the sort of film we probably should have gotten. Instead, we're stuck with the kind of movie that puts all its interesting ideas right up front at the start, and then proceeds to spend it all in one place. I'm not sure what kind of narrative strategy you call that. Nor can I recall, off the top of my head, the last time I ever saw a movie make that kind of mistake. All I know is that it doesn't work.

The filmmakers seem to have gotten the idea of telling a more familiar cinematic trope. This would be chronicling the rise and fall of a great artist. They seem to have felt that the Citizen Kane template was the right way to go, in other words. To be fair, it is just possible for such a storytelling choice to work. There's nothing inherently wrong with it, after all. Hell, Martin Scorsese has more or less built his entire career around the idea. If this is what we're dealing with, then all I can do is turn to the director, John Grandage, and tell the plain, honest truth. You, sir, are no Martin Scorsese. Then again, the irony is I can't even tell if the film itself is all that sure of what it wants to be. A lot of this is down to the way Grandage handles his two main leads. The film seems to ostensibly be an examination of the intertwined careers of Max Perkins and Tom Wolfe. If that's the case, then what it means is that we're having to deal with an attempt at an entertaining artistic biography. This is not an impossible task, however, if you want to pull that sort of thing off right, you've got to make sure you find the right way into the material. In this case, a lot of it centers on knowing how to capture the thrill of artistic creation.

Now, to be fair once again, it is just possible to argue that there's nothing exciting in this kind story. It isn't cinematic enough. There's nothing there to "pop" right off the screen. I know that's what Peter Debruge thought in his Variety review of this film. The first thing he does there is to set up a maxim. "Of all the fruits of genius that exist in the world", he writes, "writing is perhaps the least dramatic to depict onscreen (web)". My fundamental problem with this line of reasoning is how it ignores the other examples of where the trope was done right in the first place. If there was no inherent dramatic potential in any story of the creation of art, then films like Amadeus, The Player, Adaptation, and Barton Fink would never have become the critical darlings they are today. It's not the film's basic premise that is the problem. It's just that Grandage can't seem to figure out how the make the damn thing go right. The whole thing comes out rushed and poorly thought out, like they ran out of time.It starts out on decent enough footing as we see Perkins going through his daily routine. I suppose if you want to pinpoint where the first off-note begins, then it would have to be the moment when the narrative passages of Wolfe's prose are recited. Now, to be fair, there's nothing wrong with Look Homeward itself, it's just that the way Law reads it makes it come off sounding a bit too self-important for its own good. I get the impression that the novel requires a tone of guarded understatement bolstered by a barely audible sense of Romanticism. Here, Jude Law sounds like he's practicing for a future role as Marc Antony in the next Julius Caesar adaptation. If that were the case, then I'd have to declare this hypothetical production a bust before it even began filming. This sense of grandiosity is the only character note that Law can seem to find for Wolfe, and its one in a series of missteps that serve to harm the film. It serves to make a flesh and blood writer into a histrionic parody of real life.

If I had to give anything like a legitimate character note to Law for the role, then it would be to learn how to measure out the truth. By that I mean that perhaps it's best to portray or paint Wolfe in more restrained colors. He should be this young neophyte with a head bursting with ideas, that's true enough. However, he should also be handled with a decent amount of subtlety. Start him out as reserved, then gradually let the precocious genius emerge from his shell over the course of the film. Even then, his way with words should be measured and careful. It should be done in a way that let's the audience know they are dealing with a genuine wordsmith, here. Maybe even one who can go on to accomplish great things. He just needs to learn how to control both himself and his gift, first. Now that I read over all this, it almost sounds as if I'm describing all the problems Law has with his acting, in general, more than the character in particular. And so it goes, from start to finish.The worst part about the whole affair is that the film loses sight of whatever it is it wants to be. The great reason for this is because it keeps stacking too many plates onto the table when just one or two would have been all that's necessary. Does it want to talk about the birth of a great book? Okay, let's do it. Does it want to look into the life of a great editor? Sure, why not. Does it want to chronicle the rise and fall of a great artist? Throw it in, come what may! The resulting loss of narrative focus is the almost inevitable result, and no amount of talent in front of or behind the camera can find a course correction great enough to set the whole thing on a right axis. It's an almost textbook testament to hubris, and biting off way more than you can chew, or are in any way prepared for.

That's a shame, really. Because it does seem as if there might have been the faintest glimpse of a good idea tucked away somewhere in there among the lost threads. Thomas Wolfe is not the most household of names, anymore. He's more like the leftover curiosity of a bygone Modernist Age, these days, I believe. One of those authors who survive mainly by the skin of their teeth in college English classes. It's shame enough in that it turns out he can be of useful help in a general literary sense. It's easy enough to figure out why guys like Stephen King might drawn to him as a source of inspiration. The fact of the matter seems to be that Wolfe spent his entire career asking two central questions. What is writing, and what is this freak of nature known simply as "the artist" or "the writer". He was particularly curious about the role of the artist in relation to the business of real life (whatever that turns out to be).

The net result of these concerns is that it pins Wolfe down forever as one of the great, unspoken mentor figures for aspiring writers. He's someone that a younger version of Steve King would have turned to when he was nineteen years of age, hungry, and desperate to leave his own imprint in the annals of the written word. For anyone in that situation, stumbling across a book such as Look Homeward, Angel or Of Time and the River is probably something very close to running across a piece of Mana from Heaven. That's because both books are, in essence, about the discovery of the writing life, and of how to go about pursuing it, at least as far as Wolfe was concerned. I'm not saying he's the best, or only writing instructor out there. There are plenty of others, and it stands to reason that what worked for Wolfe isn't the best course of action for others to pursue, especially not for those with a family to support. Still, Wolfe does appear to be one of the voices to take advice from, every now and again.The best reason I have for saying this comes from the prologue to Angel, where he observes the following: "This is a first book, and in it the author has written of experience which is now far and lost, but which was once part of the fabric of his life. If any reader, therefore, should say that the book is "autobiographical" the writer has no answer for him: it seems to him that all serious work in fiction is autobiographical-- that, for instance, a more autobiographical work than Gulliver's Travels cannot easily be imagined.

"This note, however, is addressed principally to those persons whom the writer may have known in the period covered by these pages. To these persons, he would say what he believes they understand already: that this book was written in innocence and nakedness of spirit, and that the writer's main concern was to give fullness, life, and intensity to the actions and people in the book he was creating. Now that it is to be published, he would insist that this book is a fiction, and that he meditated no man's portrait here.

"But we are the sum of all the moments of our lives--all that is ours is in them: we cannot escape or conceal it. If the writer has used the clay of life to make his book, he has only used what all men must, what none can keep from using. Fiction is not fact, but fiction is fact selected and understood, fiction is fact arranged and charged with purpose. Dr. Johnson remarked that a man would turn over half a library to make a single book: in the same way, a novelist may turn over half the people in a town to make a single figure in his novel. This is not the whole method but the writer believes it illustrates the whole method in a book that is written from a middle distance and is without rancor or bitter intention (web)". It's a bit wordy, here and there. However, the main point is understandable enough on its own.

All Wolfe is talking about there is something James Baldwin was able to sum up in a sentence: "All art is confession". Or put it another way, T.S. Eliot came to believe that, no matter the genre, or type of story you have to tell, if the fictional narrative is able to have any kind of legitimate truth inside its web of lies, then at least the writer can be said to have found something of value. By that, Eliot meant that the real advance to be made in the artistic life is when the work of art can be just as much of a shaper of the artist in a positive direction, just as much as the story itself needs the writer in order to take its final shape. In that sense, Eliot seems to view the art of writing as very much its own type of mental health therapy, if that's what you want, of course. Thomas Wolfe might have intuited something of these basic facts, and it would have been interesting to get a film which was able to hit all these high notes in a satisfactory, and above all, an entertaining fashion. Instead, we're stuck with what we got.The point here is that the filmmakers had a rich mine to tap into, and missed the target. Instead of a deep and engaging dive into the writing life, we're left with a by-the-numbers equivalent of an old, faded dramatic approach to biographical drama storytelling that is perhaps long past its sell by date. If they wanted something audiences could sink their teeth into, it should have been focused more on the story of one writer's breakout success, and left it at that, instead of trying to cram the entire history into one film on the model of a Shakespearean tragedy. For some reason, that just seems to have been the wrong way to tackle the subject, and I think a lot of it might be down to the fact that nothing all that exciting was there to be found in the rest of Wolfe's career, or that of Perkins, for that matter. That one moment of breakout success seems to have been the highlight of both their lives, after that, it was back to the task of literary composition as just another, normal, day job. Now, to be fair, there's no shame in such a denouement. Indeed, it is just possible that reaching such a mundane sounding conclusion is all the happy ending that a lot of decent enough artists are willing to ask for.

It may be the truth, it's also less dramatic than whatever journey might be taken to reach that point. That seems to be the real problem a movie like Genius has to struggle with. The filmmakers seemed to have trouble locating just where the heart of the story, and hence its dramatic potential, truly lay. That's pretty much the point of no return for any storytelling enterprise, unless you're willing to backtrack a little, retrace your steps and see where the wrong turn was taken. That's the soundest writing advice for any artist to bear in mind. Which is what makes the filmmakers' inability to learn that simplest of lessons all the more disconcerting. The most likely reconfiguration of the script would have been easy enough. This ain't rocket science, or anything like that, after all. And yet, here we stand, with an abortive script, and a so-so film. There may one day be a definitive look at the collaboration of Thomas Wolfe and Maxwell Perkins. Right now, however, I'm afraid that Genius is just not that film.

No comments:

Post a Comment