The fact this isn't the case tells me it's more of mistake to rely on the so-called "quality" of any given film production than is normally assumed to be valid in most movie-going quarters. For what it's worth, I've also heard talk that the importance of movie "stars" is something that's on the way out as far as modern fandoms are concerned. This could either good or bad. The only constant I've been able to find, the one that has proven the most reliable over the years, all boils down to a single question. Is the writing good? If the answer can manage to be yes, then I don't care how poverty row the "production" side of things gets. You could strip it right down to no real props or background, just a bunch of unfamiliar faces saying the lines on an undressed sound-stage, like Thornton Wilder's Our Town, and all I'd still care to know, even then, is whether or not the narrative itself is able to hold up to close scrutiny.

I say all this as prelude to a simple observation. I want you to know that I can't be bothered to give much of a rip about how well Kenneth Branagh does either in front of or behind the camera. I don't know how that makes me sound, and I'll swear I don't care. All I know is he's got one of those MST3K type reputations in the industry, and among audiences. He's accused of being over-the-top, with an incurable hankering for "Ham 'n Cheese", no matter what film he makes, or is in. It's the kind of thing that acts as a distraction for most people. The minute he starts doing his thing, whatever that is, he gets folks laughing at him, like this unintentional Ringling Bros. clown. The main claim in all this is that he makes himself impossible to take seriously as an actor, for some reason. To which, all I can say goes as follows: "Good for him, where's the story"? If we're going to go the whole Hot Topic route on this, drop me a postcard, cause I fundamentally count myself out of all such considerations. To me, the gossip columnist approach to works of fiction is the gutter where all legitimate criticism of art goes to die. And I have too much respect for the medium of storytelling to even think of writing like that.So that means when it comes to talking about Branagh's next film, if you want to know anything about plotting, characterization, or themes, all that boring good stuff, then you've come to the right place. If it's a Soap Opera you're looking for, then aren't there still 24 hour cable TV channels for that sort of thing? I don't know, I've never bothered to look any of that up. I just took a wild guess, here. Either way, the answer remains the same, no. I'm here to concentrate on the importance of story, as story, nothing more, and never less. With that in mind, let's talk Agatha Christie. I said a moment ago that names like Kate Hepburn tend to get lost in the sands of time. I don't know whether that's a basic rule of thumb, yet it does seem to be a cruel fate for a lot of once great talents that perhaps shouldn't be forgotten. I guess that's what makes Christie's ability to hang on for so long all that more remarkable. She's an exception that proves the rule, and yet she is also one of the most common of phenomenons to any longtime bookworm. She's a reliable dime store rack novelist, and she's still hanging around, while other great practitioners in this trade (and here I'm thinking of names like David Goodis or John D. MacDonald) have long since faded from memory. I'm not saying this makes her bad, by the way.

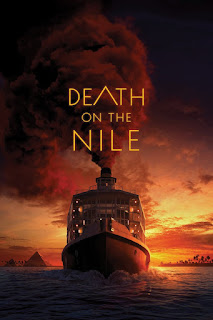

Far from that being the case, I think I'd have to go so far as to call her one of the undisputed geniuses of the Mystery Noir genre of writing. What would be interesting to me is to figure out just what it is about her work that makes her linger in the memory after such a great passage of time. John Fowl's The Collector used to be a Very Big Deal to audiences everywhere, until one day he wasn't, and now everyone wonders who the hell I'm talking about? Christie still doesn't seem to need that much in the way of an introduction just yet, and its something like a modern marvel in a short term memory loss culture like ours. Whatever the case, stories like Death on the Nile are still regarded fondly, whereas I'm not sure anyone has an idea who Mickey Spillane is. To this day its held up as one of the best examples of the genre, and it has proven famous enough to have gained at least two prior adaptations to the Cinema and TV screen, first with Peter Ustinov, and second as part of the classic David Suchet series. Branagh's efforts make it a trifecta, which brings us to the important point, the story itself.

The Story.

The worst lesson life can teach you is regret. Maybe it's because we're just accident prone by nature. Perhaps none of us are as very good at paying attention as we should be. You could fill several volumes with all the reasons there are in the world for it. In my case (Tom Bateman), all that happened was simple. I fell in love. Her name was Rosalie Otterbourne (Letitia Wright). She was a charming girl, to say nothing of her more than formidable Aunt. Salome (Sophie Okonedo) might have been the real talent in their family, yet Rosie was the one with all the brains needed to put that talent to good use. As you might expect, they make quite a team together. I'm just lucky to have met them both. In fact, I might have just been the luckiest man alive. It's not the sort of notion anyone like me ever expects to entertain, and so here all of us were, almost like the picture postcard of one big, happy family, all alike and everything. I say almost on account of my mother, of course, bless her solid as a rock mind, and just as immovable if you want to know. That's were the trouble really began.You know one of the best things about falling in love is when you find that its reciprocated. Rosie and I are incapable of prying our eyes from each other. And mother, heaven help us, knew it. To say she was reluctant to grant us her approval is a bit like saying the maiden voyage of the HMS Titanic hit a bit of rough patch. Mother (Annette Bening) is the type who tends to make up her mind about a person just once, and then its carved in stone. She started to do the same with Rosie, and words were exchanged, as they always are in this sort of thing. I don't know how, yet for the first time in ever, I managed to at least put a stall on the hammer and spike. Mother didn't relent, of course. However, she did agree to a wait-and-see period. It's cold comfort for change, so far as it goes. It's also probably the best deal anyone has ever been able to get out of her. We agreed to go on holiday together, Mother, Rosie, Salome, and I. A nice little vacation where each could get to know and size each other up. Rather let's say mother was willing to "examine" Rose and Sally. For a while, at least. It's the fairest she's ever been, and yet it still puts me in mind of auctions at a cattle market, or worse. I wonder how that woman ever managed to find a family of her own. Then again, perhaps that makes me a form of punishment.

We planned our holiday in Egypt, of all places. On a quaint little tour up the Nile. We booked passage on the passenger steamer Karnack for the journey, and were spending a day or two in the Valley of the Kings, awaiting departure. That's the place where all the pyramids and statues of the discarded gods reside, you know. Have you ever been in such a setting? The noise of that place consists of just the wind sighing through the disused doors, halls and passage ways of the burial chambers. While all around the effigies of men and women with the faces of dogs, falcons, cats, and crocodiles stare down at you. Either that or you'll round a corner a find yourself confronted by the carved, memorial faces of long forgotten monarchs and their queens, towering several feet above you. Their open eyes casting who knows what kind of judgment on this intruder for another time and life. It's easy for the imagination to misbehave in a place like this. To an infant child, it might as well be a valley on the planet Mars.I got bored, presently, of course, and decided to do a bit of kite sailing. I'm not sure I recall just which pyramid I decided to climb in order to do it. If you decide to stare at me askance for it, all I can do is tell the truth. I knew the winds would be perfect up there. It might have been illegal as sin, yet perhaps some good did come of it. It allowed me to run into an old friend of mine, M. Hercule Poirot (Branagh). We go back a ways, yet we hadn't caught up in some time, and this all started out as a very pleasant surprise. When I asked him what he was doing in the Delta, he admitted the whole business was somewhat convoluted. What it boils down to was that he was there breaking something of an unofficial iron-clad rule. While its true my friend is in the business of being a private investigator, he does not, as a matter of course, usually hire out his services as a body guard. What made him change his mind in this case was that he met Simon (Armie Hammer) and Linnet Doyle (Gal Gadot).

Their story almost sounds like a perfect image of me and Rosie. Introduction to one another at a party, spent a surprisingly good time getting to know each other on first acquaintance, and then they felt the need to keep doing it until both of them achieved the same goal that Rosie and I are still having to strive for. The happy couple joined us on the Karnack as part of their honeymoon. The reason Poirot has agreed to tag along as security has to do with the person who introduced man and wife to each other. Back then, Mrs. Doyle was just Linnet Ridgeway, another one of the product of England's wealthy, landed gentry, complete with an estate of which she would be the future heiress someday. Linnet had somewhat of an isolated life because of this. I don't know the details of her family, yet it paints a picture in my mind of a local Family Name that casually squandered away its potential good will in the countryside of which they were a part, to the point where a reverse form of public shunning set in, and it may have left a less than positive effect on the Ridgeway's daughter. The only friend she was able to make in all that time was Jacqueline "Jackie" de Bellefort (Emma Mackey). They were chums from childhood up until that fatal night when Jackie brought Simon, as her fiance, to same the same club as Linnet.The most ironic part of the whole affair is that Lin didn't just steal Jackie's steady away from her, he decided to call off his original engagement for another. There's awkward, and then there's the fury of a woman who feels herself scorned. That's how Jacqueline seems to have taken the whole turn of events. She can't seem to have let it go, either. Ever since they were married, the Doyle's would be going about their own concerns, and then Jackie would turn up, just there, out of the blue. At first it seemed harmless to the newlyweds, and then it soon became obvious that Jacqueline was stalking her former fiance, and she probably had nothing except glared daggers for Linnet. It was this that made the Doyle's seek out Poirot, and ask for his assistance, So there were in the same boat, a couple of happy wanderers, and handful of other fellows travelers, most of them friends or acquaintances of Linnet's. That's where all the trouble really started, so far as I'm concerned. When we all gathered to board that boat. Perhaps the strongest memory I have of that moment is one I'll probably never be able to forget.

It happened as we had all disembarked from our hotel, and were gathering together at the Aswan dockyards that would take us to the Karnack. As we were nearing the gang-plank, there stood Linnet. She'd regaled herself in the sort of robes one expected to find on the shoulders of Egyptian royalty. As she looked us over, like a queen surveying her realm, Linnet quoted a bit from Shakespeare, "I contain immortal longings in me". She also later on remarked that we had, "Enough Champaign to fill the Nile". Then she casually tossed the contents of her glass into the river, without a care in the world. I do not know much about gods. The last time I was ever in a church must have been when I was baptized. However, the Nile, I think, is one of those rivers that are able to make one understand how it could be taken for a strong, brown god - sullen, untamed, intractable. Patient to some degree, at first recognized as a frontier, useful, untrustworthy. Yet always something to be respected and feared.

My ancestors were the sort of Celts that used to live in caves, and paint symbols on their foreheads to ward off the wrath of the gods. It's funny nowadays, of course. However, I could never shake the idea that if one of them had been there that day, and seen Linnet be so cavalier with the river, he'd have likely pointed out that it's never a good idea to be rude to a goddess. There may be a sense of patience in the Nile, when it comes to dealing with her subjects. Just as the minute you disrespect it, she can swallow you whole. The horrible thing is that, bearing in mind what happened next, you could almost make the argument that it's exactly what happened. Our first night was raucous and uneventful, then Jackie caught up with the Doyle's at one of the Karnkack's port calls, and the atmosphere became tense and acrimonious. A day or two after Jacqueline decided to grace the couple's honeymoon with her presence, Linnet Ridgeway was dead, and Simon Doyle had a bullet fragment in his leg. Linnet had fancied herself as Cleopatra, and Simon as her Marc Antony. So what does that make them now?

Whatever the case, the facts were we had a homicide victim on our hands, the boat still has a ways to go before it can reach the nearest port, and so that means all of us are trapped on board with a murderer. I was almost about to be thankful that Poirot is here. In a sense, I still am. However, the man is uncanny at his job, and then what do you do when the facts of the case have a nasty way of drawing you in? It's been speculated over whether trapped animals experience a sense of fear as the walls close in. Something tells me there may be more of a connection there than we realize. All I know is that I've made a mistake, and things have gotten too far out of hand. That's the reason I'm composing this letter. I you're reading this now, it means that either I'm dead, or else Poirot has found out the truth, or perhaps even a little of both. For what it's worth Rosie, I never meant any of it to go this far. I was only thinking of the both of us, and of your Aunt. And I am so, so sorry. Please forgive me, darling.

Agatha, Bill, and Branagh.

Like, for instance, it is possible to tell a detective story that breaks with the normal formula, here and there. Though I've got to admit this is a rare experience to have when either reading or watching examples of the genre. Most of the authors I've watched or read tend to go the play-it-safe route, and let the formula do the talking for them. The handful of notable departures from this pattern have been with the likes of James M. Cain, John D. MacDonald, Raymond Chandler, Graham Greene, Alfred Hitchcock, and even Arthur Conan Doyle, the artist most identified with pioneering the Noir genre, and giving it its set form. It's the sort of claim that does manage to hold up under scrutiny. The thing to note, however, is that even as he was busy establishing all the familiar bells and whistles of the genre, Doyle was also one of the few practitioners who was willing to break the mold if it enhanced the story. The result in his case was a corpus of work where the ability to mix and shake up the pattern set is best on display. In fact, a surprising number of Doyle's stories don't feature murders at all, and are more concerned with questions of theft, blackmail, kidnapping, or the framing of innocents for crimes.It was and quite frankly remains one of the most accomplished examples of versatility that the genre has ever seen. It also appears to have been something that guys like Chandler, Hitchcock, and the others mentioned above were able to pick up on, and put to good use.

It's what accounts for the shared sense of a wider range in each of the authors listed, and probably accounts for why these remain the best remembered out of the entire history of the genre. Agatha Christie is interesting, in that respect. On a surface level, it appears as if she really does go the play-it-safe route. It's a contention that manages to be true enough, while also still selling her somewhat short. Christie might not break any new ground in a formalistic sense, rather her actual accomplishment rests in the degree of literary details she is able to either find within, or else pack into the tropes of the genre. Sometimes one gets the sense of a parodic commentator quality about Christie's work. I know that's the case in novels like A Pocket Full of Rye, where it clear she's writing one of the first genre parodies in existence, a textual precursor to later genre satires such as Clue (1987), or Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993).The thing to note, however, is that even when she's clearly poking fun at her own chosen field, Christie always does so with more than just tongue in cheek. There's always this lingering sense of literary awareness in her stories. Whenever she's firing on all cylinders, this constant sense of literariness and the story itself usually mesh well together into a pretty damn good reading experience. It's what seems to be the case with Death on the Nile. It was written at the middle high point of her career, and it too contains a decent sense of allusion in its plot. A better way to say it is that there is another book tucked away within the folds of her own story, one that informs the nature of her narrative, and acts as both a springboard from which to launch, as well as a wall of sources from which she can bounce and riff off of. In Christie's case, the main under text to Death on the Nile seems to be Antony and Cleopatra.

This was a plot element I did not expect to run into, and yet the allusive parallels are there, baked into the text. Some may debate over just how seamless this narrative guiding thread is used in service of the story. My own experience is that it was a pleasant surprise that didn't detract from the mystery at all. Indeed, I'll have to admit it actually serves to enhance the overall reading experience. This appears to be an element of the text that Branagh was able to pick up on when consulting the book for adaptation, and its a key aspect that the director appears wise enough to have left intact, while also maybe going a step furthering in trying to help the audience understand both the allusion, and what Christie herself appears to have been up to with it, by baking the Shakespeare play into her own work of fiction.

From a literary standpoint, understanding what Christie is up to means having to look at several plot elements one at a time, and then seeing how they all fit to together. In this case, it means a brief detour into the meaning of Shakespeare's play, what Christie thought of it, and how this determined her use of the play in Death on the Nile. That Christie would use a work like Antony and Cleopatra as a guiding thread for her own novel is interesting. In some ways, the play can be spoken of as having a significance. It's not given the same recognition of perhaps a Julius Caesar or Hamlet. Yet it is admitted as being one of, if not the best specimen on a list of Shakespeare's major works. For me, the story amounts to the culmination and fulfillment, or end of what might be termed the Bard's "dark phase", or Problem Play period. Charles Williams, in The English Poetic Mind, views it as the first time a solution has been reached to the various dilemmas presented in all the other famous tragedies.

The play he wrote and performed just before this one was Macbeth, a work with much higher regard in both critical and popular circles. Williams sees it as the author writing at the lowest possible point, the ultimate example of Shakespeare in a Richard Bachman frame of mind, in other words. If Macbeth is the literary nadir of the Bard's personal career, then Antony and Cleopatra serves almost as an automatic reply, the two plays serving as a kind of informal call and response to each other. What makes it significant is that it was also the last major tragedy that he ever wrote. There's not much else that can be labeled as Tragic in his repertoire after the composition of the Egyptian play, either. With the possible exception of Coriolanus, everything else Shakespeare ever wrote afterwards almost tends to fit him into a dramatic, fairy tale mode of writing. It's as if he just no longer had anything Tragic to say about mankind, after a certain point. Like his capacity to see the Tragical aspect of things was tapped out. I've spoken of the author as writing in a "phase", and have described it in terms of a series of Problem Plays. What makes it interesting from a critical perspective is the way it neatly opens and closes with a pair of book-ends, with his final Problem Play being a sequel to the very first one.

This literary "period" began with Caesar, and it encompassed the likes of Othello and King Lear, as well as both Danish and Scottish plays. The Ballad of Cleo and Antony is the play that brought Shakespeare's whole Problem Period to a conclusion, ending more or less as it began, providing a curious, yet satisfying sense of closure in its symmetry. It is possible here that a paraphrase of an old Neil Young can provide just the kind of metaphor what kind of literary stepping stone Antony and Cleopatra represents of in Shakespeare's career. With this play, he'd found a way "out of the black, and into the white". Or at least there's one way of looking at it, if that happens to make any sense.

It would be easy, looking back now, to dismiss a lot of it as just the writer suffering from a cumulative case of the Mid-life Crisis syndrome. Just "Old Bill" starting to feel his age, and taking it all out on paper, or parchment as the case may have been. However, I think that kind of misses the point. It's true enough to claim that Shakespeare wrote down his own troubles as a form of personal catharsis. However, what brought about the whole Problem Cycle was one of those instances where the personal and the public intertwine. At a certain point in his career, Shakespeare found himself confronted by the changing tides of history in Tudor England. He was witnessing the birth pangs of the modern age, and that kind of process was not without its growing pains. The speed of the progress at which his day and age were traveling was so much that the playwright felt the same as the vast majority of his contemporaries. There were a lot of public institutions, social mores, and old standbys that seem overturned in the blink of an eye. So in other words, "not at all like our own times, in any way".

The changes of modern life were happening so fast that the Bard of Avon felt the need to find at least some sort of bearings in this new, and growing situation the world found itself in. Hence we find the writer starting to ponder over the big questions, such as to be, or not to be, and is the major fault of things in the stars, or in ourselves? Hence, the presence of the Ides of March, the Contemplation of Life and Mortality all in a single, human skull, along with the Dagger of the Mind. All of these images and concepts were the natural artistic response to a sense that the time was out of joint. For a good comparison of this same thing, take a good read over all the poetry that arrived in the aftermath of the First world War for a good analogous idea of how Shakespeare and his own contemporaries all felt.

With Cleopatra, and her final curtain call, Big Bill seems to have found some sort of helpful perspective on things. The play is still a Tragedy, yet its told with a difference. The main players are out of joint, yet the fault is no longer felt to be in the stars, but in themselves, and Tony and Cleo seem to be one of the few tragedians with just a hint of self-awareness about it. It's not enough to make either of them want to change their mind about things, and in that sense, the play is a good examination of egoism out of control, and the consequences that sometimes wind up getting paid for it. However, the best tragedies always suggest that the solution of a Problem, even if it amounts to the removal of the main characters from the playing field, is somehow enough to help set things back to rights once more. It's what allows the citizens of Dunsinane or Elsinore to celebrate the downfalls of Claudius or Macbeth. That same principle of operation is in effect with Cleopatra and Antony. Their passing from the stage is what allows a world ready for renewal to bring an end to a period of stagnation, and start toward growth once more.

With this in mind, Shakespeare seems to know not just the material he's working with, yet also the two main leads. The names and the faces have changed, yet its clear the writer recognizes the familiar faces underneath the latest mask. Whether you call them Romeo and Juliet, Othello and Desdemona, Lord and Lady Macbeth, or even Claudius and Gertrude, it all comes down to the same trope, or set of characters. Sometimes it's correct to call them the Star-Crossed Lovers, yet I think the best term for each is to label them the Twin Egoists. The trick to love, Shakespeare found out, is that if it's to ever be a reality, then the one thing that has to get out of the way is yourself. That's something even Antony and Cleopatra never seem to realize. They and their earlier iterations all seem to have this unhealthy self-regard rambling about in their heads, and is it any wonder when they both proceed to lose it from there?What marks the Egyptian play out from all those earlier examples, however, is the welcome sense of perspective. The writer has managed to work his way toward such a clearer view of the proportion of things, that he can now view this long-time trope with a more detached sense of pity, the kind that allows him to recognize the problem for what it is, how to solve it, and then simply put it away for good, then try and find out what's down the road apiece. In that sense, things worked out pretty good for Big Bill, yet Agatha Christie was still pretty much correct, so far as I can tell when she claimed: "To me, Cleopatra has always been an interesting problem. Is Antony and Cleopatra a great love story? I do not think so (197, web)". Laurence Oliver indirectly goes so far as to back her up on this notion.

"I never really thought a lot of about Antony - as a person, that is. I mean, really, he's an absolute twerp, isn't he (ibid)". The interesting part is how this appears to be an idea that Williams might agree with. In his study, he notes how neither "love-affairs nor diplomacies (90)" are the real, main action of the play. As a result, both men can be said to back up Agatha in her claim. Which means the real focus has to be sought elsewhere in the text. Williams seems to have hit the target when he notes how "it does seem as if all the harm that happens to (Shakespeare's, sic) chief characters - from Falstaff to Timon - arises because each of them has some preconceived idea, some preliminary emotion, about life, and therefore, largely, about the way in which other people will behave...Antony and Cleopatra have it about their own capacity to deal with themselves and one another and the world. They all have it; they all lose it; and they all suffer intensely while losing it (92)". This could be the key note of the play, and one that Christie may have been smart enough to pick up on, as the entirety of Death on the Nile reads like a somewhat deliberate, creative re-shuffling of Antony and Cleopatra. That's not even the weirdest part. The strangest thing is being able to claim it's just possible that Branagh has picked up on this.

Conclusion: A Satisfying Shakespearean Riff.

If I had to come up with a good way to describe the way Christie reshuffles the original cast of Shakespeare's Tarot deck, and uses it for her own purposes, then I think we'd have to zero in on the four main players in Agatha's drama: Linnet, Simon, Jackie, and Poirot. It is just possible to claim that each of them serves as an analogue of their Shakespearean originals. There's a scene in the film which I've already referenced, and yet it helps to bring it back on stage at this juncture. It's the moment in the film where Linnet tries to claim the title of Queen of the Nile for herself, even going so far as to recite one of Cleo's own lines. What the character is trying to do here is take control of the narrative to suit her own desires. However, the gambit itself proves her false. She's more like a fatally unfortunate version of the figure of Octavia. She's not the true queen in this story. That part rightly belongs to the character of Jacqueline, with Simon being her willing accomplice as the Antony figure. That just leaves the question of where Poirot fits in with this established dynamic. The answer is provided once you cast your thoughts back to the original play, and realize that he is Christie's version of Octavius Augustus Caesar. As such, he's the bringer of order to the Tragic, Shakespearean scene of the crime.In terms of the film's overall character dynamics, both Christie and Branagh use their knowledge of the Egyptian play to pit these three main figures against one another. Like Antony and his illegitimate "one true love", Simon and Jackie are characters who fit the Elizabethan mold. As Williams might have pointed out, like a lot of the Bard's character's they are slaves to their preconceived idea of things. "Falstaff is certain of the way in which Prince Henry will behave. He is armed against the world everywhere but there, and his is wounded directly through that weakness...Troilus has a - rather anxious - preconceived idea on the proper behavior of a beautiful young woman who is in love with him. Othello has it about his wife; Lear about his daughters. Macbeth had it about the advantages of kingship (92)". For Simon and Jackie, it's their shared inability to "deal with themselves, each other, and the world". The band U2 once claimed that "a liar is someone who won't believe anyone else", and that's kind of a good description of the motivation behind the crime at the heart of both the book and film. The villains are such prisoners of their small notions, that they both find it impossible to shake off, even as both seem plainly aware that it is slowly leading them to their certain doom.

All of this plays right into Williams' observation that "the greatest opposition is between what Antony and Cleopatra think they are, and what in effect they prove. They are both experienced in politics and love; they both imagine themselves able to deal with politics and love - they have each tried them often enough. And they cannot; their preconceived ideas are destroyed, they are destroyed by the force which has been awakened. Well, but so was Macbeth, so was Lear (94)". It's just part of the natural territory of the kind of story that both Agatha Christie and William Shakespeare are telling.

If all this sounds heavy-handed, or like a dry slog, the real good news is I can report that's not the case at all. On the contrary, this is one of those cases where the critic goes into a movie with little the nothing to go on in the way of expectations, and then emerging an hour or so later more impressed than expected. I suppose it is possible to nitpick certain dramatic choices, here and there. The way Branagh approaches some of the more dramatic scenes in the flick are somewhat reminiscent of the faults his detractors cite him for. The curious thing to me is how it couldn't amount to any sort of deal breaker. At least not in my case. The reason I'm able to say this with reasonable confidence is because I decided to play it safe and take a look at the two other major adaptations of this novel. The 1970s Peter Ustinov production is okay for what it is, yet I never got the impression that I was watching something all that special. Meanwhile, the later David Suchet episode was hampered by additions to the plot which seemed there more for the sake of padding out the runtime, rather than any spark of creativity.

In each case, I came away stunned by the conclusions each was forcing me to make. I don't know how difficult this will be to believe, yet here goes. Ken Branagh actually does it better than those other two. My guess is that's more of a jaw-drop statement for others, more than it is for me. If this is the truth, then all I can do is shrug and just chalk it up to life in general, either that or some inscrutable luck of the draw. If I had to take a guess as to why this should be the case, then the best answer I can offer is that it seems as if Branagh has been on a learning curve ever since he broke into films. His early efforts, the ones that earned him his reputation (and here I'm thinking of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein or Hamlet) are the work of an obvious maverick who is still learning how to make the camera work for him on a pay-end basis. In his most recent outings(such as Dunkirk, and the like), these ironic tendencies keep getting scaled back in proportion as Branagh is able to gain his footing as both an actor and director. He seems to be learning how to make up for lost time, in other words.

With this new Christie adaptation, he seems to be building upon the strengths he's gained over the years. If there is any lingering sense of leftovers from Branagh's old style, then the good news is they don't get in the way, and manage to take their leave as the film goes on. On the whole, though, nothing I saw indicates that he's as bad as he's claimed to be, especially back in the day. Instead, the director once more shows that he has a steady workman's hand for this kind of material. That can be more of a challenge than many in the aisles would assume. I think there's a mistake that's easy to make about the Detective story. The thinking goes something like, "If the whole damn thing comes complete with its own formulas, then what else is there? All anyone has to do is phone it in, and you're set". The problem is if that's the case, then it's a wonder that fans keep returning to books like The Hound of the Baskervilles over the years. If it were really that simple, then the genre itself would cease to matter over a short course of time, and yet that still doesn't account for the continued popularity of the genre.

The real truth remains the same. There's just as much of a genuine Art to the Noir Thriller, as in every other genre. The real skill comes in knowing how to keep the audience glued to their seats, or the pages, and so Branagh has been doing a good job at it. There's a certain type of suspense that comes with the Noir territory. It's a taught, and gradual slow burn release that let's the tension in the story build to a level where the narrative has the reader feeding from the palm of its metaphorical hand. It's the same kind of strategy you can find in films like Psycho, or John Carpenter's Halloween, stories where a palpable sense of threat is introduced, and then the audience is left to squirm on the ledge, hoping that the characters can find a way out of their predicament. This is the type of practice Branagh has found in Christie's story, and it's to his credit that he's found the best possible way of putting it to good use. It's for all these reasons that I find it easy to recommend a film like Death on the Nile.

No comments:

Post a Comment