According to Bev Vincent, "When Stephen King started working on the first story of the first book

that would become the Dark Tower series, his intentions were nothing

grander than to write the longest popular novel in history. Now a

grandfather in his late fifties, King looks back with sympathy and

understanding at the youthful hubris that gave rise to such an aspiration. “At

nineteen, it seems to me, one has a right to be arrogant. . . . Nineteen is the

age where you say Look out world, I’m smokin’ TNT and I’m drinkin’

dynamite, so if you know what’s good for ya, get out of my way—here comes Stevie.” The Lord of the Rings inspired King, though he had no intention of

replicating Tolkien’s creations, for his inspirations went beyond that epic

quest fantasy to embrace romantic poetry and the spaghetti westerns of the

1960s and 1970s. After graduating from college, he decided it was time to

stop playing around and tackle something serious. He began a novel “that

contained Tolkien’s sense of quest and magic but set against [director Sergio] Leone’s almost absurdly majestic Western backdrop (275)". Earlier on in the same book, Vincent elaborates a bit more on what has to remain the quirkiest idea that ever occurred to the still reigning King of Horror. "The story that would become"

The Dark Tower series "had its genesis almost a decade before the first" installment "appeared in F&SF, when King and his wife-to-be, Tabitha Spruce,

each inherited reams of brightly colored paper nearly as thick as cardboard

and in an “eccentric size.”

"To the endless possibilities of five hundred blank sheets of 7" x 10"

bright green paper, King added “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came”

by Robert Browning, a poem he’d studied two years previously in a course

covering the earlier romantic poets. “I had played with the idea of trying a

long romantic novel, embodying the feel, if not the exact sense, of the

Browning poem.” In an unpublished essay called “The Dark Tower: A Cautionary Tale,”

King says, “I had recently seen a bigger-than-life Sergio Leone Western, and it had me wondering what would happen if you brought two very

distinct genres together: heroic fantasy and the Western.” After graduating from the University of Maine at Orono in 1970, King

moved into a “skuzzy riverside cabin” and began what he then conceived of

as a “very long fantasy novel,” perhaps even the longest popular novel in

history. He wrote the first section of The Gunslinger in a ghostly,

unbroken silence—he was living alone—that influenced the eerie isolation

of Roland and his solitary quest. The story did not come easily. Sections were written during a dry spell in

the middle of ’Salem’s Lot, and another part was written after he finished

The Shining. Even when he wasn’t actively working on the Dark Tower, his

mind often turned to the story—except, he says, when he was battling

Randall Flagg in The Stand, which is ironic since both Flagg and a superflu

decimated world became part of the Dark Tower mythos many years later (7-8)". That's the closest I think anyone's ever come to granting a basic outline of how King contrived his most erratic narrative.

It's a story that both Vincent and the author himself have related time and again over the years. There's nothing very new to be said about it, as of this writing, except perhaps for one overlooked element. It has to do with, of all things, not any famous literary text (or at least, maybe not

directly) but rather a filmmaker. I'm talkin specifically now about an Italian filmmaker named Sergio Leone. However strange this may sound. it kinda-sorta turns out he's one of the key components that King used in constructing his grandiose, yet somehow forever incomplete secondary world. He's yet another part of of the tale Vincent and King have to tell about how the Tower had its genesis. Ever since catching a fateful viewing of

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly at a local movie theater in about the year 1967-8 (

web), King has made no secret of the impact that the artistry of Leone has had on his own work as a writer. This appears to be one of those deep influences for the author. Something that has been allowed to become at least part of the artist's personal storehouse of potential Inspirations. In his 1981 non-fiction book

Danse Macabre, King even devotes a few pages to Leone and his filmic creativity. As is typical of the author, he brings Leone up in the course of discussing the art of the Horror genre. To be specific, he's contemplating how a work like

Frankenstein can become its own modern form of myth?

"The most obvious answer to this question is, the movies.

The movies did it. And this is a true answer, as far as it goes.

As has been pointed out in film books ad infinitum (and possibly

ad nauseam), the movies have been very good at providing that cultural echo chamber... perhaps because, in terms of

ideas as well as acoustics, the best place to create an echo is

in a large empty space. In place of the ideas that books and

novels give us, the movies often substitute large helpings of

gut emotion. To this American movies have added a fierce

sense of image, and the two together create a dazzling show.

Take Clint Eastwood in Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry, for instance.

In terms of ideas, the film is an idiotic mishmash. In terms of

image and emotion—the young kidnap victim being pulled

from the cistern at dawn, the bad guy terrorizing the busload

of children, the granite face of Dirty Harry Callahan himself—

the film is brilliant. Even the best of liberals walk out of a film

like Dirty Harry or Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs looking as if they

have been clopped over the head... or run over by a train.

"There are films of ideas, of course, ranging all the way

from

Birth of a Nation to

Annie Hall. But until a few years

ago these were largely the province of foreign filmmakers (the

cinema “new wave” that broke in Europe from 1946 until about

1965), and these movies have always been chancy in America,

playing at your neighborhood “art house” with subtitles, if they

play at all. I think it’s easy to misread the success of Woody

Allen’s later films in this regard. In America’s urban areas,

his films—and films such as

Cousin, Cousine—generate long

lines at the box office, and they certainly get what George

(

Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead) Romero calls

“good ink,” but in the sticks—the quad cinema in Davenport,

Iowa, or the twin in Portsmouth, New Hampshire—these pictures play a fast week or two and then disappear. It is Burt

Reynolds in Smokey and the Bandit that Americans really seem

to take to; when Americans go to the films, they seem to want

billboards rather than ideas; they want to check their brains at

the box office and watch car crashes, custard pies, and monsters

on the prowl.

"Ironically, it took a foreign director, the Italian Sergio Leone,

to somehow frame the archetypal American movie; to define

and typify what most American filmgoers seem to want. What

Leone did in

A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More,

and most grandiosely in

Once Upon a Time In The West cannot

even properly be called satire. O.U.A.T.I.T.W. in particular is

a huge and wonderfully vulgar overstatement of the already

overstated archetypes of American film westerns. In this movie

gunshots seem as loud as atomic blasts; close-ups seem to go on for minutes at a stretch, gunfights for hours; and the streets

of Leone’s peculiar little Western towns all seem as wide as

freeways (57-58)". A page or two later, while still discussing

Frankenstein as an example of a new modern

Myth, King once more brings up the significance of Leone's achievement. The funny thing is that he does so by pairing up the Man With No Name alongside King Kong, of all characters, saying, "Like Eastwood in Leone’s spaghetti westerns, Kong is the

archetype of the archetype (61)". It might not seem like much to go on, yet perhaps King has left his readers with some interesting food for thought when it comes to a good starting place for unpacking Leone's particular brand of artistry. To start with, King makes a distinction between films of Ideas, and what I'm going to call a reliance on modern

Emblems. It's a phrase I'm borrowing from scholar

Michael R. Collings, and his 2001 book

Towards Other Worlds.

In the course of a chapter with the stimulating title of Stephen King, Richard Bachman, and Seventeenth-Century Devotional Poetry, Collings theorizes that the author of books like Carrie and The Regulators has taken the Renaissance concept of the Emblem, and "transferred it into an appearance that renders appropriate and acceptable to modern audiences (150)". While the imagery of a book like The Regulators "belongs largely to the world of prose", it is the writer's ability to take the "Cultural icons of suburban Middle America" and treat them as a form of Modern Emblemology, that makes King able to bridge the gap between Idea and Image mentioned above in Danse Macabre. What's interesting to note about Collings take is that the cinema of Sergio Leone is able to fit into King's rubric of modern Emblems (149-50)". I think Collings efforts need to be highlighted here, because unless that happens, the full significance of his words will get all too easily overlooked. What he's saying in this chapter is that not only does Stephen King's artistry owe a great deal to the literary practices of the Age of Shakespeare, he also goes a step further by perhaps leaving room for applying the same consideration to the work of the director of Once Upon a Time in the West. Collings only mentions Leone just that one time, in passing, while keep his focus solely on King. The idea that a guy who writes a book like Christine might be a literary heir to the practices of Elizabethan Drama is a hard sell for most of us.

What are we to do with the notion that the same Renaissance dramaturgy applies to a man who makes films in which Dirty Harry runs around filling most of the cast full of lead? I'll have to admit it's more or less impossible to believe that films like

A Fistful of Dollars amounts to anything like a Story of Ideas, as King calls them. At the very least, this has not been any major part of the reputation that Leone has garnered for himself, whether among critics or audiences. Very few of us can see any reason to take a film like

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, seriously. And so one day I ran across a book about Leone, and somewhere very near the beginning of the text, I made a discovery. It counts as no more than one of those minor revelations tucked away in an otherwise passing comment. Yet I'd argue that if we zero in on it, it might be possible to discover an interesting reason for considering the creator of the Man with No Name as having perhaps a greater integral relation to Stephen King's

Dark Tower Mythos than has previously been assumed. Even the most dedicated

Tower Junkies assume that films like

TGTB&TU amount to little than jumping-off points, something like a simple yet necessary puzzle piece that was required to unlock the door to the artist's Imagination. However, if the work and scholarship of Sir

Christopher Frayling is anything to go by, then there might just be a more vital yet hidden connection between Sergio Leone, and the various tales told about the character of Roland.

The Director and the Poet.

A lasting reputation is a hard thing to come by, whether in the Arts, or in real life. It's one of the great truisms of life, yet it's also a fact that's proven to be a problem for some artists more than others. I can't tell at this point in time where the career of someone like Ryan Reynolds will be in a decade or so. Yet it might just be possible to claim that guys like Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg will still find their reputations going strong. This is also a problem that a director like Sergio Leone doesn't have to worry about any time soon, even many a long year after his passing in the late April of 1989. A lot of the reason for that goes back to what King said about him. In putting the Spaghetti Western genre on the map, Leone has pretty much guaranteed himself the kind of immortality that seems durable enough to survive the changing guard of tastes and expectations that most film-going audiences are prone to with the passage of time. It's an acknowledged fact, yet that still doesn't explain how he managed to pull it off in the first place. There's a tale worth telling there, yet the problem I've discovered with doing that is most of us are very poor students of history, even if it's on a subject that we love. Nor is this anything like a modern phenomenon, either. It seems like the only way to get anyone interested in a historical figure like George Washington is to talk about the time he chopped down a cherry tree, rather than just recite a catalogue of the dry bone facts about his life. He has to be a

character, in order to be a man.

In other words, if you want people to remember you, even if you're telling nothing but the honest truth, you still have to organize all those facts into an entertaining story before anyone even pays attention, much less remembers who you are, or what you did. Some may point out how unfair this seems, and I'll have to admit they're right. It also doesn't change the fact that you can't really see anything or anyone unless you first believe there's a value in them. For some odd reason, real life just doesn't seem to work any other way. As a result, before I can even recite the facts about the life of the artist, I've got to make sure you remember who he is. The best way to do that is to find out the Art in Real Life, and let it do the talking, at least to begin with. With this goal in mind, the best place to start talking about the director of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly is through the lyrics of a song by Jackson Browne:

"He came 'round here with his camera and some of his American friends

Where the money is immortal and the killing never ends

He set out from Cinecittà through the ruined streets of Rome

To shoot in Almeria and bring the bodies home He said

I'll be rich or I'll be dead

I've got it all here in my head

He could see the killers' faces and he heard the song they sang

Where he waited in the darkness with the Viale Glorioso gang

He could see the blood approaching and he knew what he would be

Since the days when he was first assisting The Force of Destiny

He worked for Walsh and Wyler with the chariot and sword

When he rode out in the desert he was quoting Hawks and Ford

He came to see the masters and he left with what he saw

What he stole from Kurosawa he bequeathed to Peckinpah From the Via Tuscolana to the view from Miller Drive

He shot the eyes of bad men and kept their deaths alive

With the darkness and the anguish of a Goya or Van Cleef

He rescued truth from beauty and meaning from belief (source)".

You can hear the bare facts of Sergio Leone's life, and then forget anyone ever told you anything. Couple all that with the legacy he's left behind to pop culture, and you're bound to remember at least something of the man. As far as the actual memory of pop culture is concerned, there's just one question to ask. Who the hell is this Sergio Leone guy, and what makes him so damn special anyway? Everything I know of this filmmaker comes from the pages of Chris Frayling's Sergio Leone: Something to Do with Death. So to summarize a long and rich personal history, this is what happened. The child was born into and artistic family, to start with. There seems to be very little doubt about that. Whatever else may be said about Sergio Leone, the first significant factor that he slowly became aware of as a child, was that his parents were artists, and that they liked to cultivate a similar temperament in their only son. To repeat, the lad grew up in an artistic household. This fact must be kept clearly in mind, else the significance of what follows will not be apparent. As Frayling lays it out in further detail:

"Sergio Leone was born on 3 January 1929, in Rome. Some sources state

that he was born in Trastevere, others that he came from Naples. In

fact, he was born in Via dei Lucchesi, in Palazzo Lucchesi, near the

Trevi Fountain; but he spent most of his childhood and youth (from the

age of two to twenty) in Trastevere. His father Vincenzo was nearly

fifty years old, and his mother Edvige Valcarenghi- whose stage name

was ‘Bice [short for Beatrice] Walerian’- had married him thirteen

years previously. Sergio was the first and only child of the marriage,

and as he recalled, ‘the event was treated by both of them as if it was a

miracle’. His mother had almost given up hope. Neither of Sergio’s parents originated in Rome. Vincenzo was born in

Torella dei Lombardi, in the province of Avellino near Naples, on 5

April 1879. His family owned a small estate in the Irpinia. Sergio Leone

liked to say that ‘my ancestors come from the campagna- the area

around Naples’. Edvige’s family came from Friuli, and her father was

proprietor of the Russian Hotel (no longer in existence) in the Piazza di

Spagne, linked to the church of Trinita dei Monti by the Spanish Steps,

part of the most elegant quarter of Rome. So she was Roman ‘by accident’, born there in 1886. She met Vincenzo in 1912, when they were

both given contracts by Aquila Films of Turin: he as an ‘artistic director’ and actor, she as an actress. They married in 1916, and ‘Bice’

retired from the screen a year later to devote her energies to setting up

home. She never worked as an actress again (25-6)".

Leone's father, Vincenzo, seems to have been from a reasonably well-to-do, if not wealthy family. There was enough finances so that Leone's grandparents were able to send his father to what appears to have been some kind of prestigious educational setting, one that was run by "the Salesian Fathers at Cava dei Tirreni (26)". From there, Vincenzo was sent to Naples to study for a career as a lawyer, yet he soon displayed the kind of rebellious temperament which would one go on to define his own son. Leone the Elder soon put off his studies to be a legal eagle. According to the Dollars Trilogy director, "In parallel with his legal studies, my father was drawn to the

artistic milieu. He found many friends there. Important figures such as

Eduardo Scarfoglio, the great- and powerful- writer and journalist

and poets and playwrights such as Italo (Roberto) Bracco. He knew

Gabriele d’Annunzio well- they had been to school together . . .

While

he studied for his degree in jurisprudence, he worked as an actor and

director with an amateur theatre company...‘His family thought that my father was

practicing as a barrister in Turin, but in fact he was a member of a

touring theatre company ... it became difficult to work under his real

name. The family would have learned the truth. And they would have

disinherited him, broken off all contact. You must remember that at

that time, the theatre was really taboo in a family such as his. If he’d

said he wanted to be an artiste, they would have treated him like

Pulcinella (ibid)".

From there, Vincenzo soon began to make his way into Italy's Pre-War film industry. He never seems to have found quite the same level of fortune either in front or behind the camera like his son would later do. However, he was able to make a living in the business of moving images. By the time Sergio was born, his father had "graduated" from actor to cinematographer. Coming of age as he did in such a family, the young boy found that his parents were always willing to encourage him to use his Imagination. In this sense, the future director can be spoken of as having enjoyed, for however brief a span of time, something very close to a childhood idyll. It makes Leone the beneficiary of a by now familiar setup up. It's one that's not always typical of someone who is first born, and then grows up with an artistic temperament, yet it does seem to have happened often enough in the past so that it's possible to speak of a number of artists whose lives can be said to fall into a familiar pattern. This is the one where all the right ingredients for the nurturing of a creative childhood somehow manage to fall into place, and whatever nascent artistic streak might lie hidden in the child's mind is given the room and space necessary for it grow and thrive. It's a pattern which only a lucky handful have ever been able to experience and enjoy. A list of names who belong to this illustrious category include the likes of Jane Austen, Edith Nesbit, C.S. Lewis, and Jim Henson. Sergio Leone seems to have been one of them.

As always, however, there is a trick to the tale, and this includes the list of artists mentioned above. Out of the four names listed, perhaps only two of them can be said to have enjoyed this childhood idyll to the fullest possible extent, whereas others found this Dream of Youth shattered by unforeseen events. In the case of Nesbit and Lewis, this came about when his mother and her father all found an early death due to illness when their children were still beyond the reach of ages ten to twelve. Even Henson might be spoken of as having experience a variation of this warped predicament in the pattern when an older brother of his became the victim of a tragic car accident, another young life full of promise, and therefore snatched away to become just another small town James Dean. Out of that entire company, it seems as if only Austen was allowed to experience the fullness of the Idyll of Childhood. The rest found their experiences to be a mixture of the sweet and sour. The "good news" for young Sergio Leone is that his schism in the pattern didn't come in the form of any personal family tragedy. All that happened was the world around him just lost its mind, is all. It happened in the form of the outbreak of World War II. Before that, Mussolini and his faction had risen to power, and the once cozy lifestyle that Leone, along with his family and friends had known wouldn't return for quite some time, afterwards.

To summarize a long story, whatever plans and hopes Sergio's parents might have had for their only child came to an abrupt and uncertain halt when the society around them all began to be shifted and controlled by a handful at the expense of the many. As a result, the endurance of Italy under Fascism became one of the defining experiences of Leone's coming of age. In later years, both critics and fans would point to this underlying theme of an ongoing skepticism of authority and the law running throughout the director's films. It seems that a lot of this anti-establishment mindset found its roots in Leone's experiences during the war. Anyone who wishes to gain a sense of how the advent and fallout of the Mussolini years left their impact on the growing mind of the artist would do well to hunt down a copy of Roberto Rossellini's 1945 masterpiece, Rome: Open City. That is a picture made in the crumbling aftermath of Fascism's collapse. Think of it as the Italian version of American Graffiti, except this time it's set right at the end of World War II, and the stakes are way higher. Rossellini's film details how a group of disparate survivors of the War either find ways of making new lives for themselves in in this vaguely familiar, yet unknown landscape, or else fail entirely. This is something that Leone and his whole extended family had to put up with as well. They made it out alright, and yet it left the future director with an unbreakable sense of suspicion of politics and politicians ever after.

This can be seen in the countless portrayals of shady and shiftless lawmen who often can't be distinguished in any meaningful way from the various outlaws and badmen who populate Leone's larger than life version of his stylized American West. The funny thing is how it was most likely during this very same time, when life was made difficult for all of Italy, that the creator of the Man with No Name encountered one of the underremarked upon influences that would go on to shape his Art. It is also this same influence that forges a more direct connection between the Spaghetti Western and the fiction of Stephen King. Frayling writes about how "In the prewar years there was a further form of year-round entertainment on offer to children, albeit in the open air of the Gianicolo

Park, near the Piazzale Garibaldi. On occasional weekends Sergio

Leone was taken there by his parents to see the glove puppets known as

the burattini, often operated by Neapolitan families of puppeteers.

Their name was said to derive from buratto,

the coarse cloth used by

Southern peasants both for sifting flour and to make the hard-wearing

sleeve of the puppets’ gloves. This brand of puppet theatre pre-dated

the commedia dell’arte, but the stories usually enacted were in a line of

descent from those of the commedia: the misfortunes of Pulcinella or

Arlecchino or Gerolamo at the hands of the wily Brighella, as enacted

by hand-waving puppets in masks. To the young Leone, they were magic.

"Often his parents had to drag him away from repeated viewings

of the same performance, or prevent him from slipping off to yet another glove-puppet theatre. ‘I remember late one afternoon’, Sergio Leone said in 1976, ‘as I

was returning home to Trastevere, I

walked past one of the puppet theatres

which was just closing . . .

Behind the lowered curtain of the theatre, I

could hear raised voices, and the sound of things being thrown about.

Looking behind the theatre, I

could see the puppeteer and his wife

having a scrap. It was a friendly fight, and very Neapolitan. But just

after the puppets had been hitting one another with wooden sticks on

the stage, here was this couple hitting one another with the wood and

cloth puppets, whose “gloves” by now had become all too visible. As I

watched this bizarre event, I understood- in my childlike way- that

there were things as they appeared, and things that went on behind the

things as they appeared. Fiction and reality. The fables of the theatre,

and the human theatre which was more serious, tougher, more shabby,

and pitiful even. I had just grasped my first lesson in the meaning of the

word “spectacle”. And it happened before I

went to the cinema for the

first time.’

"The burattini were just one form of traditional puppet theatre on

offer in Rome’s public spaces. Since Sergio’s father Vincenzo hailed

from Naples and could speak the Neapolitan dialect, he had a particularly soft spot for them. But there were also occasional visits from the

pupi Siciliani of the South. These were rod-puppets, of up to five feet in

height, rather than small glove puppets. They were used to perform

Sicilian variations on stories of heroism and bloodshed, originally dating back to the era of Charlemagne: the same stories that were collected

in the Old French epic The Song of Roland (written shortly after the

First Crusade and describing an actual military disaster of ad 778). But

these had been updated and made even larger than life in the Renaissance by the Italian poet Ludovico Ariosto, as Orlando Furioso (8-9)". It is at this exact point that any Tower Junkies out there will snap to attention and be, perhaps not just on the alert, but also stunned and amazed, and here's the reason why. For all intents and purposes, it seems as if the maker of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, has given readers a more direct link between his work, and all the effort that Stephen King expended in the creation of the Gunslinger. I'll admit this is something that jumped out a me the first time I read those paragraphs.

It was and remains interesting to know that in a case where one artist provides part of the initial inspiration for another, there was a still further, unnoticed level of influence that more or less provides a closer connection between a pair of otherwise unrelated works. As Bev Vincent outlined, King drew his idea for Roland and his world in part from his first, influential viewing of TGTB&TU, way back in 67. From that moment on, he decided to pattern his Dark Fantasy protagonist into a version of Clint Eastwood's Man with No Name. The only major add-on was that King decided to christen his literary Gunslinger with the moniker of Roland. Here's why that's important. According to King's own testimony, he got the name off of an old Robert Browning poem that he was assigned in College English. This seemed to have been all the writer ever knew when it came the initial outline of his hero. It turned out to be one of those creative choices that stayed intact all the way to the final completed paragraph. Now, however, with the addition of Frayling's information, it becomes possible to say that the influence more or less works both ways. Not only was King not the only artist to take some of his ideas from the legends of Roland, the same also applies to one of his main inspirations, Sergio Leone.

It's something that's always lingered at the back of my mind for some time now. How one of those simple seeming, tossed-off bits of trivia made in passing can sometimes be another vital piece of a long and complicated puzzle. In my case, the riddle in question has less to do with the quality of the finished Dark Tower series, and more with what influences went into it. Beyond that point, I'm not real sure what I'm after here. I suppose it "could" be some sort of pointless hope that untangling the various strands and threads of the web that is the Tower series will maybe grant me some sort of clue as to why King would want to devote so much of his life and career to such an undertaking; especially when we're dealing with a such a patchwork, hodgepodge crazy quilt like the Roland's universe. Then again, that sounds just like the sort of aimless goal that somehow managed to act as a lure for the author. The only difference is I'm not a writer, just a critic. So in a sense, I've got at least some excuse for what I'm about to do next. I'd like to see how our picture of King's Dark Fantasy series changes when we add Leone's own Roland influences into the mix. I don't know what that picture looks like just yet. In order to find out how it might appear, the best course of action I can offer right now it to start with Leone's own Inspiration. Who was Ludovico Ariosto, and what is the Orlando Furioso? Here's what I know.

The funny thing about pairing Leone up with Ariosto is the remarkable number of similarities the film director has with this otherwise unconnected poet from the Italian Renaissance. In order to figure out what these match points are, the background of yet another artist needs to be understood. Much like with Leone, Ludovico Ariosto seems to have come from a family with claims to belonging to 15th century Italia's wealthy gentry class. At least that's what the circumstances of his birth tell me. His father was a military commander in the province of Reggio Emilia. While this was where the poet was born, Ariosto would go on to share at least one other quality with Stephen King. Ludovico chose, in a very haphazard kind of way, to settle on becoming a writer of place. In other words, just as King is now considered a the key aspect of the landscape of Maine, so Ferrara, Italy has become for the reputation of Ariosto. The major difference is that Ferrara still counts as one of the major metropolitan areas of Europe, whereas even the cities of Maine are surrounded on all sides by the wilderness of New England. Getting back to the shared similarities between the author of the Orlando Furioso and Leone, recall what I said about Ariosto achieving his goals in a haphazard way. It's a statement that can be taken literally, and the main reason for that has to do with the social life the poet grew up in as a boy.

There's a monologue that Orson Welles delivers in The Third Man that manages to act as a neat summation of the situation that Ariosto was born into. "In Italy, for 30 years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed. But they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love. They had 500 years of democracy and peace. And what did that produce? The cuckoo clock (web)". For better or worse, that was the kind of experience Ariosto learned to familiarize himself with for most of his life. It's an experience that manages to encode itself into the fabric of the Orlando Furioso. We'll get to that in a minute. For now, the best account of Ludovico's personality is given by Charles P. Brand, in his introductory text to the poem. I'd argue that Brand gives us the best snapshot of who the poet was when we turn to a brief section of chapter 2 which focuses on a number of satires that Ariosto penned as part of his minor works. According to Brand, "all have their point of departure in some contemporary situation in which the poet was involved and which he uses to explain his conduct or his views and to criticize his society.

"...Each of them, as I have said, is associated with some event or situation in the poet's life...Each of them supplies the biographer with significant information about the poet's activities and movements, but they are particularly revealing of his reactions and attitude to his environment; they show him considering the sort of practical problems which face most men - whether to accept promotion and increased responsibility or refuse it; to move elsewhere or to stay home; whether to take a wife or stay single; how to educate a child. In discussing these personal problems the poet tries to establish a personal philosophy. What are his guide-lines for taking decisions in this harassing world? His philosophy, like his diet, is simple: knowing what he likes best:...[I understand my own affairs better than anyone else.] It seems largely to coincide with that of Horace (whether consciously or by chance who can say?): a simple life, with a simple table and simple clothes: a quiet life without show or ambition, free from hazardous travelling, spent at home within sound of the bells of the Duomo; a humble life without pretentious titles and responsibilities; a free life not tied to capricious patrons and tyrannical rulers; a stable domestic life close to the woman he loves

'These being my tastes', Ariosto seems to say, 'how could I be expected to go suddenly off to Hungary with the Cardinal, or to govern the bandit-ridden Apennines, or to accept a permanent post in Rome? It is, after all, reasonable and consistent, this attitude of mine.' His attitude is determined by the way he is made, by the society he lives in and the people he meets, so many of whom he dislikes and, he shows us, dislikes with good reason. So the strictly satirical components accompany the lyrical: he accuses others in excusing himself. His targets are similar to Horace's: pretentious people, hypocrites, flatterers, materialists of all sorts, social climbers, shady business-men. These are the people he dislikes at the courts, and in the Church, and he makes his dislikes known, sometimes with the smiling irony of Horace, sometimes with an invective worth of Juvenal (22-24)". Earlier than this, Brand gives us an even neater summation of the kind of personality that Ariosto seems to have been. "These letters seem to support the picture that has come down to us from his contemporaries of a kindly, well-meaning, conscientious man, certainly no saint, too conscious of his own as well as others weaknesses to be sanctimonious. His morals are those of his age and he society: he lives as virtuously and as honestly as he reasonably can: he has...children, a long attachment to a married woman: he has to scramble like everyone for benefices and favours; he accepts...the dubious conduct of his patrons and superioris.

"But he is not malicious or grasping: he cares conscientiously for his dependent family, and he is widely liked for his wit and charm. He is not ambitious for wealth or honours - he wants a quiet life, the company of his Alessandra and his friends, the familiar streets of Ferrara, the leisure to read and to write. He lives his life as one might expect the author of the Furioso to live it (14)". It's also possible that this is just the kind of life that a guy like Sergio Leone might have desired for himself. He's known these days for creating an entire form of stylized cinema violence, one where the trappings of civilization can come off sounding like someone's idea of a sick joke. It's true this has become the director's greatest legacy. Yet it's also possible that, like Ariosto, it was because he knew what it was like to watch his civilization crumble around him that made Leone anxious to get whatever semblance of "normality" back for himself as much as possible. In that way, a comparison between the filmmaker and the poet becomes somewhat revealing for the shared similarities and contrasts that exist between them. Both men came of age in a period of national crisis; a time and place in which combat could break out at any moment, and blood could be spilled in the streets. It's the kind of circumstance that tends to leave some kind of mark on those lucky enough to survive it, even if it's all just mental.

The irony comes in the form of the results of these crisis moments that each artist witnessed. Ariosto arrived just in time to get a front row seat to the internal strife and warfare that would, paradoxically, become the birth pangs of Italy at its height of national glory. Leone, meanwhile, came of age just in time to watch all of that legacy get reduced to near complete rubble by the country's second spasm of national crisis. One artist got his start in an era when his country began to achieve a level of majestic grandeur for itself in terms of Art, Politics, Culture, and Social Living. The other was in time to watch it all come to an end, and a new Bronze Age take its place. It gives the detached viewer a sense of shared contrasts, with each artist confronting both the Red and the White aspects of human culture, respectively. The interesting thing to note is how this polar opposite setup doesn't necessarily detract from the similarities between Leone and Ariosto. For one thing, while the old and obscure poet was around to view the full flowering of the Renaissance, it's not the same as saying he was ever blind to the harsh realities that made it all possible. The backstabbing of court intrigues (sometimes literal) of first the Borgias and then the Medicis, and how the abuse of power could contribute to cultural prosperity.

In that sense, one of the reasons Ariosto was so anxious to acquire a simple life for himself and his family was because he knew just how fragile and precarious a balance on which the entirety of the Renaissance rested. He was a Renaissance Humanist who could take in and understand the various levels of duplicity and malice that hid itself behind the beauty of works by Leonardo and Michelangelo. This included the ability to tell the difference between the genuine good will of artists and citizens like the two famous names just mentioned, and the high-priced criminals who acted as their patrons. It was a situation he was caught up in himself, and there are plenty of indications he found this a less than satisfactory setup, no matter what scholars like Brand might think. It's true he wished for nothing more than a normal, simple life. What Brand fails to realize, I think, is that this is a desire born out of desperation, and much as it is founded on genuine hope. Ariosto is best described as an Italian Humanist who took the outlook seriously, and therefore was always aware of the various threats that the Borgia-Medici society of his own day could pose to such an outlook. It was this awareness which drove both his desire to keep his life and wants as simple as possible, and also for the longstanding streak of satire which runs through just about everything he ever wrote. This is true for the Orlando Furioso.

A Poem That's Almost Impossible to Summarize.

Here's where we come to the main text that inspired this whole article. Out of all the possible source material that Stephen King could have drawn from in creating the Dark Tower mythos, Sergio Leone's Spaghetti Westerns stands as the most notable. What I doubt anyone figured figured on was that even so much as a brief glance into the director's own work would reveal the one possible easter egg that would rival them all. I'm talking about the possibility that the creator of some of the most stylish, and influential Oat Operas ever committed to celluloid, might also have taken a great deal of his own Inspiration from the same backdrop of myth as King. The key piece of evidence for this surmise all has to do with Ariosto's poem, and the title character at the heart of it. You see, the poem itself is called Orlando Furioso. Now I'm not sure how many out there are aware of this, but the name Orlando is (in this case, anyway) just an Italian version of the name Roland. That handle also happens to belong to the main character of King's Tower series. King, in turn, was basing this character off of Leone's Man with No Name. Leone, all this time, meanwhile, was drawing Inspiration for his own films (at least in part) from Ariosto's Orlando poem. Which was, by the way, inspired by the various strands of myth surrounding this vague and enigmatic figure known as Roland. It's the kind of six degrees of influence that you could make a neat little moebius strip out, with maybe just the slightest bit of good effort.

It paints this picture of the secret and mysterious processes of creativity; a function of the Imagination that's so well hidden that even the artists involved don't have all that much of a clue its going on. I like to think it's another bit of proof that the Romantic take on the workings of literary creativity is still more or less the correct interpretation. What it says to me, in other words, is that guys like Jung were right when he claimed that the Imagination does its best work when it's dealing with Archetypes. Those are the central building blocks that all the best stories are made out of. Of course the ability to tell any kind of halfway decent story with any of them is still a gamble, even under the best of circumstances. In Leone's case, at least, it's possible to say he was able to bottle lightning not just once, but three whole times. King never seems to have been that lucky whenever it came to dealing with Roland and his world. Yet at least now it might be possible to say this much in his favor. He may very well have caught a glimpse of some kind of Archetype, however fleeting the moment may have been. The only pity of the whole deal is he was never able to chase after and catch it down on the page. Not in any sort of way that mattered, at least. That almost never happens to him in his other books, yet it's what always occurs whenever he writes about the Tower.

The addition of the Orlando Furioso to the Well of Inspiration amounts to more than just another piece of the puzzle. It's the sort of literary revelation that's able to establish and forge a genuine link between artistic mediums. In this case, it joins King's and Leone's efforts into a closer relation than I think any Tower Junkie was aware of until now. That raises an interesting question, though. What is there to this Ariosto poem that Leone might have found fascinating from an artistic perspective, and what can the actual narrative within the rhyme scheme tell us about the Archetype the writer and the filmmaker were drawing from? Well, the best place to start answering that question is to at least try and see if it's possible to provide some kind of workable synopsis for the newcomer to Ariosto's most notable work. I think it's doable, for what it's worth. I'm also pretty sure most readers are goin to be left wondering if I've just told some kind of elaborate joke, and if so, then where the hell's the punchline? If I'm being honest, I think I'd better leave that up to whoever decides to read this. Because trust me when I say, I've just stumbled upon one of the wildest, weirdest, and just plain nuts work of Fantasy ever written. For what it's worth, it won't surprise me is most just give up, and decide it's best to skip this part.

Here's a good idea of the fair warning I'm about to dish out here. I will be drawing from not one, nor two, but rather (count 'em) three sources. These represent the best chance I'll have at ever being able to summarize this story to anything like a manageable level. The first source comes in the form of a preamble introduction from an early translation provided by William Stewart Rose. He's talking about a different poem than the one Ariosto wrote, by the way. If that makes no sense, why would anyone need to talk about another poem if it's not the one under discussion? Trust me, things are just getting started. This is what Rose says happened. "This work is a continuation of the "Orlando Innamorato" of Matteo Maria Boiardo, which was left unfinished upon the author's death in 1494. It begins more or less at the point where Boiardo left it. This is a brief synopsis of Boiardo's work, omitting most of the numerous digressions and incidental episodes associated with these events: To the court of King Charlemagne comes Angelica (daughter to the king of Cathay, or India) and her brother Argalia. Angelica is the most beautiful woman any of the Peers have ever seen, and all want her. However, in order to take her as wife they must first defeat Argalia in combat. The two most stricken by her are Orlando and Ranaldo.

"When Argalia falls to the heathen knight Ferrau, Angelica flees — with Orlando and Ranaldo in hot pursuit. Along the way, both Angelica and Ranaldo drink magic waters — Angelica is filled with a burning love for Ranaldo, but Ranaldo is now indifferent. Eventually, Orlando and Ranaldo arrive at Angelica's castle. Others also gather at Angelica's castle, including Agricane, King of Tartary; Sacripant, King of Circassia; Agramante, King of Africa and Marfisa, an Asian warrior-Queen. Except for Orlando and Ranaldo, all are heathen. Meanwhile, France is threatened by heathen invaders. Led by King Gradasso of Sericana (whose principal reason for going to war is to obtain Orlando's sword, Durindana) and King Rodomonte of Sarzia, a Holy War between Pagans and Christians ensues. Ranaldo leaves Angelica's castle, and Angelica and a very love-sick (but very chaste and proper) Orlando, set out for France in search of him. Again the same waters as before are drunk from, but this time in reverse — Ranaldo now burns for Angelica, but Angelica is now indifferent. Ranaldo and Orlando now begin to fight over her, but King Charlemagne (fearing the consequences if his two best knights kill each other in combat) intervenes and promises Angelica to whichever of the two fights the best against the heathen; he leaves her in the care of Duke Namus. Orlando and Ranaldo arrive in Paris just in time to repulse an attack by Agramante.

"Namus' camp is overrun by the heathen. Angelica escapes, with Ranaldo in pursuit. Also in pursuit is Ferrau, who (because he had defeated Argalia) considers Angelica his. It is at this point that the poem breaks off. While the Orlando-Ranaldo-Angelica triangle is going on, the stories of other knights and their loves are mixed in. Most important of these is that of the female knight Bradamante (sister of Ranaldo), who falls in love with a very noble heathen knight named Ruggiero ("Rogero" in Rose). Ruggiero, who is said to be a descendent of Alexander the Great and Hector, also falls in love with Bradamante, but because they are fighting on opposite sides it is felt that their love is hopeless. Nevertheless, it is prophecies that they shall wed and found the famous Este line, who shall rise to become one of the major families of Medieval and Renaissance Italy (it is worth noting that the Estes where the patrons of both Boiardo and Ariosto). Opposed to this prophecy is Atlantes, an African wizard who seeks to derail fate and keep Ruggiero from becoming a Christian. By the end of the poem, Ruggiero is imprisoned in Atlantes' castle. However, Bradamante (who has decided to follow her heart) is in pursuit of her love, and is not too far away. It is the Bradamante-Ruggiero story that eventually takes center stage in Ariosto's work.

Other characters of importance: Astolfo, a Peer and friend of Orlando, who is kidnaped by the evil witch Morgana and her sister Alcina; Mandricardo, a fierce but hot-headed heathen; and a young knight named Brandimarte, who falls in love with (and wins the heart of) the beautiful Fiordelisa ("Flordelice" in Rose). All play major or semi-major roles in the events of Ariosto's poem (web)". Now, I think it's easy to tell what anyone who's gotten this far is thinking, and let me, not so much reassure you a guarantee that nope, I'm not high. Nor did I make any of that up. It's the synopsis of a poem by a previous writer. Ariosto's work was written as a kind of satirical sequel, somehow, to every single piece of mixed up information you just read. If the whole thing reads like a history report written in haste while on an acid high, then all I can do is quote from another of King's Inspirations. "See or shut your eyes", said Nature peevishly, "I cannot help my case (web)". It just is what it is, folks. And we are still just getting started. I haven't even gotten around to what Ariosto decided to do with all that! For information on that whole affair, I think it's telling that the best source I could turn to is Wikipedia.

"The action of Orlando Furioso takes place against the background of the war between the Christian emperor Charlemagne and the Saracen king of Africa, Agramante, who has invaded Europe to avenge the death of his father Troiano. Agramante and his allies – who include Marsilio, the King of Spain, and the boastful warrior Rodomonte – besiege Charlemagne in Paris. Meanwhile, Orlando, Charlemagne's most famous paladin, has been tempted to forget his duty to protect the emperor because of his love for the pagan princess Angelica. At the beginning of the poem, Angelica escapes from the castle of the Bavarian Duke Namo, and Orlando sets off in pursuit. The two meet with various adventures until Angelica comes across a wounded Saracen infantryman on the verge of death, Medoro. She nurses him back to health, falls in love, and elopes with him to Cathay. When Orlando learns the truth, by finding the pair's secret garden of love, or Locus Amoenus, he goes mad with despair and rampages through Europe and Africa destroying everything in his path, and thus demonstrates the frenzy that the title suggests. The English knight Astolfo journeys to Ethiopia on the hippogriff to find a cure for Orlando's madness.

"Orlando joins with Brandimarte and Oliver to fight Agramante, Sobrino and Gradasso on the island of Lampedusa. There Orlando kills King Agramante. Another important plotline involves the love between the female Christian warrior Bradamante and the Saracen Ruggiero. They too have to endure many vicissitudes. Ruggiero is taken captive by the sorceress Alcina and has to be freed from her magic island. He then rescues Angelica from the orc. He also has to avoid the enchantments of his foster father, the wizard Atlante, who does not want him to fight or see the world outside of his iron castle, because looking into the stars it is revealed that if Ruggiero converts himself to Christianity, he will die. He does not know this, so when he finally gets the chance to marry Bradamante, as they had been looking for each other through the entire poem although something always separated them, he converts to Christianity and marries Bradamante. Rodomonte appears at the wedding feast, nine days after the wedding, and accuses him of being a traitor to the Saracen cause, and the poem ends with a duel between Rodomonte and Ruggiero. Ruggiero kills Rodomonte (Canto XLVI, stanza 140[12]) and the final lines of the poem describe Rodomonte's spirit leaving the world. Ruggiero and Bradamante are the ancestors of the House of Este, Ariosto's patrons, whose genealogy he gives at length in canto 3 of the poem. The epic contains many other characters, including Orlando's cousin, the paladin Rinaldo, who is also in love with Angelica; the thief Brunello; the Saracen Ferraù; Sacripante, King of Circassia and a leading Saracen knight; and the tragic heroine Isabella (web)". The fun ain't over just yet, though.

The resolution to the entire main plot of Ariosto's poem, the titular Madness of Roland, is best summarized in passing within the pages of an otherwise unrelated book, Into Other Worlds: Space Flight in Fiction from Lucian to Lewis. It's there that another link might be established between Ariosto's poem and King's series. Green does this by pointing out that the Orlando Furioso stands as part of a specific literary tradition, one that has its roots in what the author labels as Apocalyptic Literature. This passing bit of insight is noteworthy as King's efforts with the Tower have often been labeled as an example of post-apocalyptic writing. Finding out that Ariosto's own version of the Roland myth belongs, in some ways, to what might be termed an early version, or ancient strand of this sub-genre makes for some interesting further food for thought. Even if that's the case, it doesn't erase the weirdness factor for what the poet has in store for any reader brave enough to venture onward.

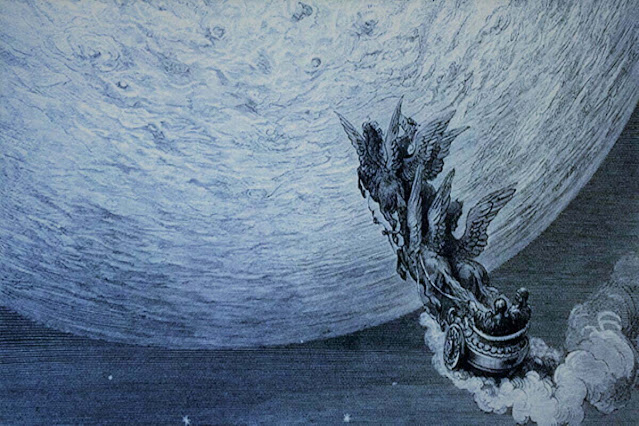

According to Green, this is how it all rinses out. "The Apocalyptic journey died hard, and when Ariosto came to send his brave and adventurous knight Astolpho to the Moon in his Orlando Furioso at the beginning of the sixteenth century, the influence was still strong - and St. John was still the Heavenly Guide. Astolpho made his journey in search of the lost wits of the unfortunate Orlando who had been driven mad by his unlawful love for a Paynim maid. Riding upon his hippogryph - a winged horse like Pegasus - Astolpho came to Paradise, on the summit of a great and unscalable mountain. After stopping for a while to admire the beauties and the wonders of this other Eden, the jewels spread everywhere in rich profusion, the brightly coloured birds, the perfection of eternal Summer, he entered the great shining palace - glowing more crimson bright than any carbuncle - and found St. John waiting for him there. The aged apostle told him that they must journey to the Moon, the nearest planet to this Earth, for there all things lost here were stored, Orlando's wits amongst them. When evening came, accordingly, they entered into the very chariot which had carried Elias up to Heaven. To it were harnessed four goodly coursers more red than flame, and as soon as St. John had gathered up the reins in his hands, away they flew, rising at a steep angle...up until they came to the Region of Fire which was popularly supposed to surround the Earth. The properties of this belt were miraculously suspended for the saint and his companion to pass in safety.

"Through all this elemental flame they soar'd And next the circle of the Moon explor'd

Whose spheric face in many a part outshin'd

The polish'd steel from spots and rust refin'd

Its orb increasing to their nearer eyes,

Swell'd like the Earth, and seem'd an earth in size,

Astolpho wondering view'd what to our sight

Appears a narrow round of silver light:

Nor could he thence, but with a sharpen'd eye

And bending brow, our lands and seas descry,

The lands and seas, which, lost in vap'rous shade

So far remote, to viewless forms decay'd.

Far other lakes than ours this region yields,

Far other rivers, and far other fields;

Far other valleys, plains, and hills supplies,

Where stately cities, towns and castles rise;

Where lonely woods extensive tracts contain,

And sylvan nymphs pursue the savage train.

"Landed on the Moon, Astolpho followed his divine guide through the Lunar scenery, which was of a classical nature with wooded parkland 'where nymphs forever chased the panting prey'. They came at last to a wide valley, stored in marvelous fashion with all things lost on Earth - from fame, fortune, empty desire, broken vows, to crowns, bribes, the 'lays of venal poets', women's wiles, and finally sense itself stored in vessels ranging from tiny vials to great vases. There Astolpho came upon Orlando's missing wits, set carefully in a great heroic vase as became the lost senses of so great a paladin. By them he found a smaller vial which held such senses of his own as he had already lost in the ordinary course of life; and this by the grace of the Saint who accompanied him. Astolpho raised to his nostrils, and straighaway all wisdom returned to him, nor did he lose any of it again in after days. Then carrying with difficulty the great vase which held Orlando's scattered wits, Astolpho followed his divine guide once more, and came next beneath 'a stately dome' where sit forever the Three Fates spinning the lives of all men, both living and to come; and in this House of Fortune, the knight saw many wonders to interest both him and Ariosto's contemporaries. When these marvels were exhausted, St. John led Astolpho once more to the flying chariot, and they returned to Earth as swiftly and easily as they had come...and brought back sanity to the stricken Orlando (24-6)". And that's all the poet gave us, folks.

I think Rick Moranis said it better than I can. "Everybody got that"?! The answer, of course, is hell, no! In fact, I'm pretty darn sure there's just a handful of question anyone can ask at this point. First off, what the hell did I just read? Second of all, what in the blue blazes does any of that even mean?!!

A Poem of Ironic Weaknesses and Surprising Strengths.

Well, here's the deal. I think it's possible to dredge a clear enough answer as to what this poem is, and what it's up to. I'm just not sure this will make it any easier to assimilate into the mindset of modern audiences, even if there's a case to be made for its overall quality as a good yarn. To put it in the most basic terms, all that Ariosto has done here is to give his readers what has to be counted as one of the first examples of the Early Modern Fantasy novel, except that here its told in poetic verse. Like all the most well known quest fantasies, the Orlando details the exploits of a band of heroes as they set out on a journey to achieve a goal which situates them within the confines of an inherently supernatural, and hence fantastical landscape. In terms of the poem's main cast, I suppose it can be considered fitting that all the main characters are knights, princesses, soldiers, and warrior maidens. As for the nature of the secondary world that Ariosto invites his readers into, the first thing to note is that it's not afraid to be bizarre. The best description I've got on that score is to say that the author presents us with a world in which the typical setup of a Fantasy story is somewhat inverted, though by no means subverted. Most stories of the Fantastic these days tend to run on one of two formulas. The first is the typical quest narrative like that established by the likes of Tolkien and George R.R. Martin. Where the setting is fantastic, and yet these are qualities that the cast of characters discover as they make their journeys.

A good example of what I mean is demonstrated by the layout of a book like The Hobbit. It's a novel that sets up the nature and layout of its secondary world with care and precision. With every chapter, Tolkien can be seen unraveling yet another part of the map of Middle Earth, and the various inhabitants and species that live there. The whole affair may be set in a mythic realm, yet it's handled in such a way that even when the reader is presented with a trio of trolls straight out of Scandinavian folklore, by the time they've all shuffled on-stage, it already comes off as no more than a matter of course. Tolkien is able to weave his spell so well that when the trolls do arrive, we just "know" that creatures like them have always been hanging around in this world. The writer makes us see them as so much a part of Middle Earth that the landscape would seem somehow emptier without them. This is the same strategy that Tolkien uses from one chapter of his book to the next. After the trolls, we are introduced to the elves, and from there, the orcs (or goblins as they are called in this story). From there, we meet Gollum, and after him, we are confronted by a type of wild wolf known as Wargs, followed by a tribe of sentient eagles, then monster spiders, more elves, and at last, human beings. The entirety of The Hobbit is a masterclass in how to lay out the nature and contents of an imaginative, secondary world for readers.

It still stands as one of the great underrated feats of narrative craftsmanship. Yet the rest of the practitioners of this format of the genre seem to have done their best to take Tolkien's methods to heart. Even if you're story is set in the kind of realm that could never exist, the general approach is to try and lay out the nature of the settings and its characters in the same quasi-cartographic exploratory nature that Tolkien uses with Middle Earth. The second type of approach used in the category of the Fantastic is what's come to be known as that of the Urban Fantasy. In this setup, the basic story template is always the same. Every situation stands as any and all possible number of variations on the idea of what can happen when the Fantastic encroaches on and into our mundane world. There have been just as many tales told in this format as there have in the more standard, fairy tale approach utilized by Tolkien. All that guys like Ray Bradbury and Rod Serling have done is to take those same fairy tale elements and apply them to modern day suburbia, and even the big city streets. The question all this history is leading up to is where does Ariosto's poem fit in with either of these categories? Which of these methods does he use in constructing his own version of Roland, and his Renaissance Mid World?

Well, that's sort of where the poet has a trick or two up his own sleeves. So far as I can tell, Ariosto tends to follow the kind of formula laid out by Tolkien, more than any other approach. In a way, this makes sense. Ariosto was writing at a time when the idea of the modern suburb wouldn't even become a workable idea until the middle of the 1950s, and even then, it's still very much an American, as opposed to a European phenomenon. So there's really no way he could have been a pioneer of the Urban Fantasy, not even long after the fact. Instead, the poet makes do with the materials at hand. Like the Brother's Grimm, he sets his epic quest in a fictionalized version of what appears to be our world as it was known or understood (for lack of a better word) during the height of the Renaissance. Also like Grimm's Fairy Tales, the Furioso tells of a world which is fundamentally Enchanted by nature. The writers spins his web of words into a realm populated by dragons, giants, ogres, and sea monsters, and our heroes take all of their encounters with these marvels in stride. This is not the kind of standard that we would expect nowadays. The way the typical Fantasy world set up tends to work for most people now goes something like this. Even if it's a Fantasy world, the general approach of the moment is to treat the enchanted realm as the kind of place where the marvelous still isn't taken for granted.

What that means in practice is, in counter-distinction to the way the typical setup was handled by the likes of Ariosto or Thomas Malory, if a modern day Fantasy writer has this situation where a knight is traveling down the road on his way to somewhere, and he arrives at a bridge with a troll hiding under it, our current expectation for this setup demands that rather than take the whole thing in stride, and treat it as a matter of course, the protagonist instead will be framed as a modern, skeptical mindset in Medieval cloths and appearance. This allows the for the moment of contact with the Fantastic to have a note of both the Uncanny and/or Sublime to the hero's initial sense of shock and awe. In this setup, St. George would be slack-jaw stunned to realize such things as dragons could even exist in his world. This appears have become something of a standard, shared approach for both Enchanted Realm and Urban Fantasy works in recent years, and I think it's possible to see why this is. This current "standard" approach represents not just a communal expectation on the part of the mass audience, but also what I can only describe as a kind of lingering sense of hope that always seems to reside somewhere in the back of the minds of all those faces in the aisles. It's this same shared faculty that makes even newcomers to Steven Spielberg's E.T. look back on that moment when the young boy and the alien encounter each other for the first time with a great deal of nostalgic fondness and expectant delight.

They've been introduced to the idea that it's possible to encounter some sort of hole in the column of reality, some rift in the fabric of everyday life that can allow the extraordinary or for the wondrous to peep in from beyond the regular bounds of the mundane. This is what we've come to expect from our Fantasy stories, and a great deal of the motivation behind it comes from a longing for the kind of Romantic outlook that might have been somewhat part and parcel even of Ariosto's period or early modernity. For certain there is a sense that it was a key feature of the era that the poet was writing about, for a given amount of "factuality". In other words, some of the sense of Enchantment of the Middle Ages was real, to a logical extent. The rest, meanwhile, can be chalked up to us Moderns projecting our own Romantic longings back into an era and time period which (let's face it) none of us really know anything about. Even Ariosto was writing of the Era of Charlemagne as an outsider looking in. For all I know, that old timer might have been working from the same shared sense for an Enchanted Past that the rest of us still live with to this day. If so, then it counts as an early example of a very Modern imaginative phenomenon. Romanticism we will always have with us, it seems. There appears to be something ineradicable about it in our nature as human beings, for whatever reason.

I can't say I'm ever going to mind this Romantic streak, all that much. I'm also going to be one of those guys who insist on keeping a level head about it all. For my own part, I enjoy exploring the past, especially in relation to myth and the creation of stories. However, you'll never get me to over-romanticize the whole deal. Even Tolkien was smart enough to know the current life he lived was preferable to being even a well stipend clerk in the Age of Chaucer. It can be seen in all the satirical jabs and barbs he hurls at the supposed heroic tradition associated with sagas like Beowulf, and other legends that followed in a similar train. That's the part of Middle Earth that I think even die hard fans tend to overlook, that it's author can be just as critical as celebratory of it. In that sense, it does make sense to me to claim that Tolkien might be working in the same satiric vein as that established by Ariosto. The way the Orlando world works is that nobody in the entire cast bats an eye at learning that they live in a world of mythical creatures. We insist on letting our own make-believe medievals have this recurrent moment of shock and awe because we are so outside the kind of mindset that Ariosto talks about, and hence, we are desperate to create and focus on any fictional scenario which would allow that moment of recognition and re-admittance into a more Enchanted frame of mind. This must not have been as much of a problem for a writer like Ariosto, even if he was just as much of an outsider as us.

Instead, his own approach carries this straight, simple, and to the point, matter-of-fact quality that tends to create a jarring effect to modern audiences, whose expectation towards the Fantastic is to allow it all the space in the world, but never before the right amount of proper dramatic build-up. In contrast to this "standard" setup, let's stop and unpack how Ariosto handles his introduction to what now seems to have become one of the most iconic creatures in the lexicon of modern Fantasy. First, let's take the way the poet sets his scene. It happens when we catch up with a girl named Bradamante. She's one of the main heroes of this little saga, and in the scene where we're about to meet her in person, our heroine is currently on the road, journeying to meet up with the other lead knight of the story, a fellow by the name of Ruggiero in Italian. In English, however, we just call him him Roger. So for those keeping score. We have a fearless maiden on a quest to find her true love, and all of it happens on account of some stuff she saw in a vision granted to her by none other than Merlin when she stumbled upon his cave (because...ya know, like ya do!). At the start of the Fourth Canto, Bradamante is conferring about what to do next with a shady character named Brunello. Ariosto proceeds to astound the contemporary reader by not only calling out the notion of inappropriate gazes, but also showing Brandy being smart about it.

Before this scene can go any further (and get really uncomfortable), some of the patrons of the tavern the two cast members are in raise a commotion that has everybody filing outside.

"She saw the host and his family there,

Folk at the windows, folk out in the lane,

All gazing upwards at the heavens bare,

As if a comet or eclipse showed plain;

There flew a wondrous thing, high in the air,

She scarcely credited, nor could explain,

A winged steed, gliding, in clear daylight,

Across the sky, bearing an armoured knight.

"Broad, and of varied colours, was each wing,

And in the midst that figure shining bright,

Since his steel breastplate, a radiant thing,

Lit all around it; westward was his flight.

Yet the creature, now, did downward spring,

And midst the mountains there, was lost to sight.

This path, the host said, the sorcerer flew,

In raiding near and far, and he spoke true.

‘Sometimes he flies straight upwards to the sky, Then sometimes seems to skim along the ground.

He bears away those pleasant to the eye,

From all the distant countryside around,

So those who are, or think they are, all sigh,

(Though he in fact will steal what he has found)

And so, the maids are careful not to stray,

But hide their features from the light of day.

"A keep, in the Pyrenees, forms his lair,

Built on high, by spells and incantation,

All made of steel, and it shines bright and fair,

The whole world shows no finer creation;

And many a brave knight has ventured there,

Yet none return from that destination,

For I fear,’ the host said, ‘naught do they gain,

But they are all imprisoned there, or slain.’

"The warrior-maid thought on all he’d said,

Rejoicing, while believing that she would,

Without a doubt, strike the sorcerer dead,

Wielding the ring, and end his theft for good.

‘Find me a bold guide, host, to ride ahead,’

She cried, ‘who knows the way, by vale and wood;

For I must not delay, my heart beats so,

But find this enchanter, and destroy our foe' (web)".

This is by no means the most significant passage in the entirety of the poem. However, it's also true that the vagaries of pop culture popularity have shaped the passage into the story's most notable one as a whole. From what I'm able to tell, this seems to have been the first time that a new fictional creature was added to the halls of Fantasy. It's this sequence above all others that has turned Ariosto and his writings into, not so much a household name, as this vague kind of underground buzz. Like the faint heard notes of a tune that are just floating around somewhere at the back of your mind. It means the poet has given us an accidentally ideal set of narratological bones to study out of the larger story fossil. In terms of judging the overall quality of the passage, what hits the audience on a first read-through of the writer's stanzas is best described as a mixed combo reaction. It's made up of intrigued interest, and the sense of something being just off-kilter enough to notice in equal parts. The real bothersome question is, "Does any of this count as a necessarily bad thing"? That's the part where it all gets very tricksy real fast. Let's look at the elements we're given to work with before reaching for any rush to judgment. The first thing we might notice concerns the prototypicality of the whole situation.

What we've got is one of the main cast in one of those quaint and cozy Ye Olde Taverns. Everything starts out on a quiet note, yet the author is quick to introduce a blended element of world-weary knowing mixed with a slow-burn tenseness that comes from Bradamante's growing awareness that the person she's dealing with is the sort of fellow she'll have to keep up her guard around. This tension, and the sense of potential lingering threat lying in wait for her sometime later on is then broken up by the commotion stirred by the arrival of the familiar winged beast. Now, if by some miracle I have made this all sound like what could be an exciting read, then there's something the reader needs to pay closer attention to. It's not just the events in themselves, it's also the way I've formatted and doled out the description of the initial meeting between Bradamante and Brunello. In setting the scene for the modern reader, I've made ample use of the narrative tropes and verbal conventions of the modern day Thriller. The reason I've done this is because it seemed the best possible approach needed to convey the kind of atmosphere the scene required to draw the audience in with the proper doses of danger. Brunello is a shady character, and while Brandy has earned the title of warrior for herself by this point in the plot, the merest possibility that her new "ally" might pose a threat of violence is what makes the scene work.

Even when it comes to explaining the emotional logic of this sequence, I am relying strictly on the contemporary novelistic techniques that has defined literature since the middle of the 19th century onward, until it has developed into the dramatic shorthand utilized above. In doing so, it is possible to say that I've altered the poet's original scheme more than just a tad. For one thing, I can be accused of bringing the nascent subtext of Ariosto's words more into the foreground, if for no other reason than for the sake of drama, and therefore keeping the audience riveted to the action, even when it is just two people in a room talking. It's all in the way you choose to use the character's dialogue, gestures, and glances that helps to ratchet up the tension in moments like this. We as an audience are put on edge from the implied threat that this lug Brunello might try to take advantage of Bradamante at some point, and that sooner or later she will have to see how well she can defend herself against him. In capable hands, this can all be the stuff that great writing is made of. So it's therefore interesting to stop and look at the actual way Ariosto handles the inherent nature of the setup he's established for his audience:

"Though dissimulation often conceals The inner workings of an evil mind,

Many a time some good it yet reveals,

And many a benefit therein we find,

Saving us from harm in life’s ordeals;

For those we meet with are not always kind,

In this our life, more clouded than serene,

Where envy bears many an ill, unseen.

"So, she dissimulated, twas fitting,

With one who was a master of the lie,

And held her position, ever glancing

At those rapacious hands that met her eye,

When, behold, a mighty noise, arising,

Filled their ears, as if from out the sky.

‘O Virgin Maid! O King, above!’ she cried,

And quickly ran to seek its source outside (ibid)".

If the modern Fantasy fan of today can find any compliment to pay to those words, then it might tend toward something like "Economy of Expression". Ariosto has summarized an entire complex scene, along with an "implied" exchange, in just two short stanzas. The best basis for comparison on offer would Tolkien's skills at brevity in summing up the Battle with the Balrog in a few short paragraphs. Even there, however, it is somewhat telling that Peter Jackson found the need to take that moment, and turn it into its own epic set piece. The reason the director of the adaptation did that was simple. The necessity of the modern rules of drama demanded it, or at any rate, something like the final results was required, so far as modern audiences are concerned. In the same way, I saw fit to take those two, short, line stanzas and turn them in the kind of descriptive prose that at the very least hints at the kind of dramatic expansion that would be required to get a contemporary reader to "buy into" the sort of conceit the poet was aiming for. For another demonstration of the sort of dramatic expansion that I'm talking about, it's useful to check out the three part rewrite that Andrew Lang gave to Bradamante's part of the Furioso in his Red Book of Romance.