Can novels have their own soundtracks? It's not a question most people would bother to ask. The most commonsense answer would be to point out that a novel is not something like a movie or a record. All a book amounts to is just a series of words on a page. There's no sound or music to go along with it. Even if its possible to say you'd like you're copy of To Kill a Mockingbird, or The Fellowship of the Rings to have its own soundtrack accompany the words as you read along, the fact remains you're not going to find it anywhere in the book itself. You'll either have to find some music that could go well with the words, or else just use your imagination as best you can.

Can novels have their own soundtracks? It's not a question most people would bother to ask. The most commonsense answer would be to point out that a novel is not something like a movie or a record. All a book amounts to is just a series of words on a page. There's no sound or music to go along with it. Even if its possible to say you'd like you're copy of To Kill a Mockingbird, or The Fellowship of the Rings to have its own soundtrack accompany the words as you read along, the fact remains you're not going to find it anywhere in the book itself. You'll either have to find some music that could go well with the words, or else just use your imagination as best you can.That's as far as everyday commonsense can go when faced with such an off-kilter question. By and large, the majority of audiences, including even the readers in the crowd, do not tend to make an automatic connection between texts and songs. The reason for this seems to be because there is no essential reason for the two forms of art to mix. One can exist just as well without the other, unless of course you're a band like the Beatles and you're trying to make a concept album with something like an actual narrative attached to it. Then the singer must learn how to be not just a songwriter, but also a kind of storyteller. That's a task that can be harder than it sounds. A lot of talented artists who make great musicians are also pretty lousy at trying to be straight-up writers. When an concept album like Marvin Gaye's What's Going On? is able to mix both music with a sense of narrative its usually an achievement that goes underappreciated by both music and book enthusiasts.

The irony is that the commonsense response itself has left the door open for certain creative opportunities. Let's recall that the answer boils down to three statements. (1) Books and music are separate artistic mediums. (2) If anyone wanted music to go along with their reading material, they would have find ways of incorporating it from vinyl, CDs, or clips off the Net. Those are about the only options anyone has left in terms of where you can get music to listen to. (3) The third and final option is to just use your imagination in order to fill in all the sonic gaps provided by the text, if any.

The good news is that it is possible to meet all three challenges, if you know how to do it. Take Tolkien's aforementioned Fellowship, most Middle-Earth geeks already have a soundtrack all neatly laid out for them and waiting in the wings, thanks to, and courtesy of Howard Shore. All anyone has to do is grab a headset, pop in the CD, open the book, press play, and begin to read. All of that amounts to one way of proving that it is possible for books to have the potential for a soundtrack.

The good news is that it is possible to meet all three challenges, if you know how to do it. Take Tolkien's aforementioned Fellowship, most Middle-Earth geeks already have a soundtrack all neatly laid out for them and waiting in the wings, thanks to, and courtesy of Howard Shore. All anyone has to do is grab a headset, pop in the CD, open the book, press play, and begin to read. All of that amounts to one way of proving that it is possible for books to have the potential for a soundtrack.I'd like to see if it's possible to go a bit further than that. I want to try something. I don't know if it's new, or anything like that. In fact all of the materials involved are all pretty darn old. However there may be a lingering sense of novelty about the whole thing for those who've never tried or thought of it before.

What I'd like to do is take a random novel, a handful of old songs, and then see what happens when an imaginative attempt is made to combine the two. I don't mean to create anything like a new hybrid medium where literature and music interchange with one another to the point of being indistinguishable. Instead, I'm trying something that I might have got from Walt Disney. Allow me to explain. In his 1940 concert film, Fantasia, Disney took the concept of the animated film, and combined it with music in a variety of ways. One of them was a mix of images and music, with the goal of setting up a mood or atmosphere. This was done in the film with sequences like Toccata and Fugue. Another was to use music in a way that told a story. This goal was best on display in Night on Bald Mountain, The Rite of Spring, and The Sorcerer's Apprentice. As it turns out, Fantasia was not the only time that Walt would find ways to utilize music in the service of a legit narrative. One of my oldest childhood memories is seeing a Silly Symphonies adaptation of Peter and the Wolf. It was an animated adaptation of the entire folktale, and it was free of any real dialogue from start to finish. Instead, the symphonic score of the legend was used to punctuate and accentuate the action and story beats happening up on the screen. The result was a film that used music to tell its story.

I think it's a technique that's been tried here and there, once or twice more, though it's never the sort of thing that has ever managed to really catch on with the public. We seem to have reached a point where we tend to like our medias unmixed. Part of the reason for this might be down to the ways we've allowed imaginations to shrink and atrophy with the passage of years. It didn't use to be like this back in the days when everyone lived in forests, and no one could live anywhere else. Back in the old, Medieval peasant cultures of Europe, most groups never minded if a fiddler decided to provide some violin accompaniment to retelling of an old folktale or legend such as that of Robin Hood. In fact, such techniques were said to enhance the experience. That's one of the reasons why storytelling minstrels flourished for such a long time in an age when books weren't really a thing like they are now (if they ever were).

I'd like to see if I can bring some of these old materials back in a minor way. It's nothing major, just a brief moment's diversion. What I'd like to do is take a text that lends itself easily to a musical soundtrack, and see what happens when we mentally use various Golden Oldies to provide something like a musical compliment or commentary for the text. I think the best choice for now is to choose a book like Stephen King's Hearts in Atlantis. I think this is the best course of action because King is a writer who likes to sprinkle the artifacts of pop-culture here and there throughout his works. He can erase 99% percent of the world's population, and then have one of Marvin Gaye's songs start to play in an abandoned, imaginary record shop. This makes King's work an ideal test case for my experiment. I want to take the narrative beats of a novel like Hearts and see if it's possible to make a soundtrack for an already established text. From here on in, I think it's best if I actually show what I intend to do, rather than just talking about it. With that in mind, let's take a bit of mental leap and see if there's anything to find.

The Narrative Setup and Track Listing.

Hearts in Atlantis is a unique work in King's canon. It is a novel with a straightforward narrative. However the way it goes about telling its story is by switching viewpoints from one plot thread to the next. The story centers on a group of differing, yet semi-related individuals at different points on a chronological compass. The main historical backdrop for the novel is the 1960s, and each plot thread takes place at a different juncture of the time period, starting with the opening segment, Low Men in Yellow Coats, taking place in 1960, all the way to the epilogue, Heavenly Shades of Night are Falling, which is set in 1999. Each segment has a different protagonist, with a different setting and focus, yet each part is able to neatly link up with each other, thus progressing the narrative and helping to establish a greater whole. It is perhaps one of King's most sophisticated, and unjustly neglected works. The way things will work is I'd like to take parts of each segment in the novel, and see if there is a song that can match up with what's going on at various points in the narrative action. The results can best be thought of as the liner notes to a make-believe concept album that will never exist.

Hearts in Atlantis is a unique work in King's canon. It is a novel with a straightforward narrative. However the way it goes about telling its story is by switching viewpoints from one plot thread to the next. The story centers on a group of differing, yet semi-related individuals at different points on a chronological compass. The main historical backdrop for the novel is the 1960s, and each plot thread takes place at a different juncture of the time period, starting with the opening segment, Low Men in Yellow Coats, taking place in 1960, all the way to the epilogue, Heavenly Shades of Night are Falling, which is set in 1999. Each segment has a different protagonist, with a different setting and focus, yet each part is able to neatly link up with each other, thus progressing the narrative and helping to establish a greater whole. It is perhaps one of King's most sophisticated, and unjustly neglected works. The way things will work is I'd like to take parts of each segment in the novel, and see if there is a song that can match up with what's going on at various points in the narrative action. The results can best be thought of as the liner notes to a make-believe concept album that will never exist.Part of the challenge in writing this piece is knowing how much to tell about the book itself, and whether or not to to throw in a regular review of King's novel into the bargain. I wound up deciding to at least try the best I can in giving my judgments on the tome as I continue matching story with song. The main reason for this is because the structure of King's text is so unconventional to the traditional standard of how a narrative should proceed. This makes a regular, straight-forward description of the story less practical than it could be if King had stuck to the normal A to Z plotting of his other volumes. That means that taking a piece of the plot from each of the novel's segments and matching them to the song which fits the moment best is a very ironic and effective solution to the problem. It allows me to treat the story in a chronological sequence while shifting from one set of characters and situations to the next. The novel itself is an ensemble piece, and the idea of framing a review around the proper decade centric music would help provide the necessary critical through line needed to bring a sense of order and coherence to the whole thing. It's all tall order, to be sure, yet I can't think of any other way this can work. So, here goes. The best place to start any of it is with the imaginary first track:

Don Henley: Boys of Summer.

This is the song I imagine as the book's main theme, if that makes any sense. If it were a movie, then Henley's song would be the one playing over the opening credits. I would argue this choice works on several creative levels. The first is in the way it helps set the tone for what's to follow. That old FM standard manages to carve out a place for itself by being both hard-bitten and hard-biting, while also maintaining a sense of nostalgia and optimism. I'd argue these are also the the constant background notes King sounds off as all the segments of his novel progress.

This is the song I imagine as the book's main theme, if that makes any sense. If it were a movie, then Henley's song would be the one playing over the opening credits. I would argue this choice works on several creative levels. The first is in the way it helps set the tone for what's to follow. That old FM standard manages to carve out a place for itself by being both hard-bitten and hard-biting, while also maintaining a sense of nostalgia and optimism. I'd argue these are also the the constant background notes King sounds off as all the segments of his novel progress.On another level, there is the song's content. Henley is dealing with the themes of youthful idealism, the loss thereof, and the romantic attempt to at least gain some of it back. The song was written, composed, and sung long before King had his initial idea that would become the seed that grew into Atlantis. And yet I'd argue that both artists are treading on at least some of the same ground as they composed their own works. It's for all these reasons that the Henley tune just felt like the right intro to all that is about to unfold.

The Platters: Twilight Time.

The first segment of the novel is titled Low Men in Yellow Coats. It centers around a young, 12 year old boy named Bobby Garfield. He's something of a half-orphan, with his father being dead and his mother living in a strange sort of haze which Bobby can't quite understand (or thinks he doesn't), and he finds himself in a somewhat aimless moment of his life. Bobby and his mother Liz live in a working class tenement neighborhood which is neither bad, nor will it ever be upscale. It rests on some uneasy middle-ground between the haves and have nots.

It's while Bob and his Ma are on their way home from movie that they see a new tenant has arrived in their humble establishment. His name is Ted Braughtigan, and he's the kind of fellow who inspires immediate reactions from all the people he meets. Bobby finds himself taking an instant like to the old man. He's nice in a grandfatherly kind of way. Liz Garfield has just the exact opposite reaction to the new-comer. It's not a question of dislike, exactly. It's a bit more complex than that. There's just something off about Mr. Braughtigan, an odd element out that she can't quite put her finger on. He just seems wrong, is all. Ted describes himself as something of a wayfarer, and that he might not

even stay long. This is a minor sort of consolation for Liz. Though

even this bit of information just acts as a signal that's something

about the old man's setup is not quite right. Liz never tells Bobby

this, but she suspects that Ted might be criminal of some kind.

It's while Bob and his Ma are on their way home from movie that they see a new tenant has arrived in their humble establishment. His name is Ted Braughtigan, and he's the kind of fellow who inspires immediate reactions from all the people he meets. Bobby finds himself taking an instant like to the old man. He's nice in a grandfatherly kind of way. Liz Garfield has just the exact opposite reaction to the new-comer. It's not a question of dislike, exactly. It's a bit more complex than that. There's just something off about Mr. Braughtigan, an odd element out that she can't quite put her finger on. He just seems wrong, is all. Ted describes himself as something of a wayfarer, and that he might not

even stay long. This is a minor sort of consolation for Liz. Though

even this bit of information just acts as a signal that's something

about the old man's setup is not quite right. Liz never tells Bobby

this, but she suspects that Ted might be criminal of some kind. There's more to it, of course. For people like Liz, there's always a bit more to it with problems like hers. One way of explaining part of it would be to say that if Liz were a mother wolf, the instant she so much as scented Ted coming from a mile away, she would turn tail and bolt off into the safety of the woods, probably never to return to that spot again. She's human, however, and has to make do with the situation as it is. Doesn't mean she'd have to like it.

The Platter's Twilight Time is the best choice I could find to represent the total atmosphere of this opening scene. The tune itself is nice and pleasant, and yet there is a neat little amount of edge to it. I don't mean to imply that the song itself is sinister in any way. It's more like the tune itself is willing to at least hint at an admission that darker elements can sometimes be waiting in the wings. Perhaps that's best reason I can find for why the Platters number works as a kind of curtain opener on the action. It's pleasant scene, yet King is able to lay the discordant notes that hint at the troubles still to come later on. It also hints that it is Ted, for better or worse, who brings this trouble with him.

The Crests: 16 Candles.

It's clear to the reader that Bobby has a less than ideal home life. What's debatable is just how self-aware Bobby is of this factor at any of the early points in the stories. I'd have to argue that he's always aware of it on some level, and was just very good at holding that awareness at bay. The good news is that Bobby does have friends who are there for him. These are John "Sully John" Sullivan, and Carole Gerber. When we first meet these two characters, they arrive to present Bobby with a card for his birth day. It's a simple and light scene that King is able to infuse a level of depth which makes us care about these figures. It's a common talent that often pops up in his works, yet I don't think he's managed to break the ivory ceiling in terms of how far people are willing to recognize and acknowledge King's achievement in this particular field. The scenes of Bobby with his friends are one of those occasions where King is able to fire on all cylinders and create a whole picture for us to enjoy.

It's clear to the reader that Bobby has a less than ideal home life. What's debatable is just how self-aware Bobby is of this factor at any of the early points in the stories. I'd have to argue that he's always aware of it on some level, and was just very good at holding that awareness at bay. The good news is that Bobby does have friends who are there for him. These are John "Sully John" Sullivan, and Carole Gerber. When we first meet these two characters, they arrive to present Bobby with a card for his birth day. It's a simple and light scene that King is able to infuse a level of depth which makes us care about these figures. It's a common talent that often pops up in his works, yet I don't think he's managed to break the ivory ceiling in terms of how far people are willing to recognize and acknowledge King's achievement in this particular field. The scenes of Bobby with his friends are one of those occasions where King is able to fire on all cylinders and create a whole picture for us to enjoy.I've chosen the Crest tune in part because of the birthday element. However it does serve a double purpose. Besides coming of age in a biological sense, a growing paternal friendship with the newcomer, Ted, helps inaugurate Bobby into the world of adult literature. This is driven home when Bobby decides to check out William Golding's Lord of the Flies. Aside from being a real life book, its presence in King's novel acts as one of several motifs or pointers to the themes King will be exploring in his text. This gives the otherwise cheerful tune an ironic echo. It's a trait that many of these Golden Oldies acquire once they land in the King-verse. We'll return to the importance of the Golding text in a moment. For now, let's skip the boring dissection and move onto:

Roy Orbison: The Comedians.

The big hook at the center of Low Men hangs on all the multiple ways that Bobby comes of age. While Ted is able to broaden the young guy's horizons with great works of literature, Carol does the same thing in a different way. This is the romance part of the feature, and for such a stock situation, King is once more able to make us care about the relationship. Both Bobby and Carol come to a slow-emerging awareness of their true feelings for each other. This plot thread reaches its Parnassus in the form of the top-most seat in a Ferris Wheel in an amusement park called Savin Rock. It's a moment he's both ready and unprepared for.

Bobby's troubled home life also makes a reappearance where a run-in with a boardwalk card sharp forces Bobby to realize that he's deliberately let his mother lead him around in a very similar fashion. The difference is the card sharp is a total stranger, so he had no trouble calling the con out when he saw it. Bobby is unsure if he could ever do the same to his mother. Nonetheless, the date with Carol leaves him with a sense of possibilities in the making, and this is one of those moments where King gives the audience and in-story soundtrack by having Bobby fall asleep as Earth Angel by the Penguins plays over a radio.

I've chosen the more uncertain and insecure note contained in Orbison's tune to represent the Farris Wheel sequence for several reasons. The first is the very simplistic fact that both scene and song revolve around carnival imagery, and in each separate work a Ferris Wheel plays a prominent part. Besides this, I think the Orbison song speaks better to the tune because it highlights a lot of the real subtext that's in the scene, and which the main character is either unaware of, or is once more simply refusing to acknowledge even to himself. This makes the hapless, love-struck note of Orbison's performance a perfect mirror for the nature of Bobby and Carol's encounter with each other.

Miles Davis: So What?

I mentioned up above that Golding's Lord of the Flies text played an important thematic role in King's book. He's mentioned it in interviews as one of the big reading moments in his life. On one level it seems to have been the book that taught him how to write tension, drama,and above all, fear, in a way that really manages to work its way into your head and go for the jugular there. I think there's another reason for its importance, one that might be an interesting pointer to the larger themes King is working with in Hearts.

I mentioned up above that Golding's Lord of the Flies text played an important thematic role in King's book. He's mentioned it in interviews as one of the big reading moments in his life. On one level it seems to have been the book that taught him how to write tension, drama,and above all, fear, in a way that really manages to work its way into your head and go for the jugular there. I think there's another reason for its importance, one that might be an interesting pointer to the larger themes King is working with in Hearts.What I'm about to suggest next is one of those out there ideas, so bear with me. Lord of the Flies functions on two levels in King's story. I think it's best to cover the second thematic function in another segment, so right now we'll just focus on the first. On the one hand, it is a text within a text. Usually the presence of one work of fiction within another is often a sign that the former text is informing the present one. I think that holds true for the way King uses it, not just in Low Men but throughout the story. One of the ways this is done in the first segment is through the way the trajectories of the three main characters, Bobby, Carol, and even Sully John, are changed or shaped in negative ways or directions. Each one of them finds a gateway to their worst impulses over the course of the novel, and each gateway arrives in different ways.

For Bobby and Carol this come in the form of both his mother, and neighborhood bully named Willie Shearman. After Willie breaks Carol's arm, Bobby carries her all the way back to Ted, who is able to help fix her. The trouble is that Bobby's mom arrive back home after going through an experience similar to that of Carol, albeit on a dangerously adult scale. The confluence of events leads all the character present on-stage except Ted throwing all the skeletons out of the closet. The kind of words are exchanged which can end and re-create worlds for all those present, which is what happens for both Bobby and Carol. It is in moments like these that I think King is utilizing the themes of the loss of innocence found in Golding's text and applying them with an impressive series of gut-punches in his own work.

When the dust settles Ted has packed his bags, and is once more on the road. Bobby decides to try and make a clean break and join him. This leads to a reveal about Ted's character that also, in retrospect makes me wonder if it was perhaps the one single misstep the author made in an otherwise perfect novel. We meet the individuals Ted is on the run from, and how impressive their reveal is will depend not so much on the mixture of realism and fantasy. Instead it's more a question of whether Ted's pursuers ever really work as characters depending on how they turn up in a later work. It's complicated, and somewhat messy, and not the real point of this article, so I'll have to shelve it. To be fair to King, the whole sequence as written is able to tug at the heart strings, and a lot of it is down to Bobby's own admission that he really is his mother's son. He's facing up to his problems, though it does something of a number on his sanity (or at least the mask he was wearing as a sane front), and that's where the real heart of the scene lies. I can see all the reasons why it would have to stay. The one question I have is whether now, and in retrospect, if given the opportunity, King might have played certain aspects of it in a minor different way? Who knows.

Either way Davis's killer and by now legendary turn at the saxophone is a perfect tonal compliment to the confused chaos of these scenes. In particular, the repeated "So what?" refrain of Davis's notes do well to highlight the indifferent nature of Bobby, Liz, and Carol, as each one slowly starts to retreat in on themselves, all of them determined to dig their own pits and lie in it.

Isaac Hayes: Walk On By.

I said a moment before that Golding's Flies had a dual significance in the novel. Part of it is the shared concept of the corruption of innocence. A more complex and symbolic aspect comes into play when the reader understands that in some ways it is the very arrival of Golding's text itself that acts as something of a herald of the coming, painful changes that are about to effect Bobby and everyone he knows, right down to the way he views the world. In doing so, King has given a real life text a walk-on role in his novel as a kind of change agent. It's appearance is a clue to the reader that there's trouble waiting in the wings, and its going shake things up around the quiet little neighborhood the cast calls home.

The way the story utilizes the Golding text is surprisingly reminiscent of fictional techniques or tropes found in old Renaissance dramas. It sounds like an unnecessary leap in logic, I know, yet I can't help being reminded of certain ideas from that era. King himself displays an interesting awareness of Shakespearean concepts like macro and microcosms in his work. He generally uses such concepts on a more indirect, symbolic level. To give the best example, it should be obvious the the fictional small-town setting of Derry in the novel It is meant to be seen as a microcosm for all the negative aspects of modern American life. There was, and still is, plenty of material out there to work with. All King had to do was take it and condense it down into a manageable format that would work well within the pages of a novel. As far as symbols go, the fictional and haunted province of Derry probably stands as simultaneously one the most famous, and symbolically neglected ideas in a work of fiction.

I think King is using the Golding text in a similar Elizabethan style, or symbolic manner in his Atlantis text. The trouble is finding the right words to describe it. I have an idea of what kind of symbol Golding's book serves as in the text. One way of describing it is as a kind of harbinger object. It's the usual function of this imaginary prop to act as a silent signal that, as Sam Cooke observed, "Change is gonna come". These sorts of changes are often presented in a work of fiction as a series of obstacles and challenges that the cast of characters must face. In Bobby's case, the biggest challenge winds up being the acknowledgement of all the troubled aspects of his situation and personality.

In Bobby's case, it's one of those once seen, can't be unseen, type of deals. As a result, his life begins to spiral out of control to the point where Carol tries (and on some level fails) to break up with him. There is one minor and very ironic accomplishment that Bobby is able to add to his name and reputation during this time. He finds Willie Shearman and pays him back double for what he did to Carol. This is an act, along with his carrying Carol home to safety, that winds up causing ripple effects in all the narratives that follow the opening act. On at least two other occasions, one character will wind up carrying another to safety.

If I had to guess what the meaning of all this is, then one answer might be that's it's part of King's rumination on just what caused the cultural revolutions that changed America in the first place. It could be that if we look at the situation of Bobby, Carol, and Sully from a symbolic perspective, the point King is making is that a lot of the revolt stemmed from the sense that the Boomers felt their parents were just incapable of being their to handle things on any mature level. This awareness could sometimes have surprisingly positive effects, which we will get to in a moment. For Bobby, at least to start with, it marks a low, black period where he becomes your standard angry, aimless neighborhood delinquent, same as the guys who beat up Carol. He even goes so far as to identify himself with the protagonist of Golding's book. What halts and changes this degeneration is a letter Bobby receives one day from Ted, letting him know that the closest father figure he ever had has made good his escape.

This is one of those times when it was like the right song was always meant to be there for just this particular occasion. Walk on By is really Burt Bacherach song, yet the late, great Isaac Hayes was able to re-tune it in a brilliant manner that gave it the necessary amount of desperation, edge, bite, and meaning. This makes it the perfect sonic vehicle to carry the meaning of the closing moments of Low Men in Yellow Coats. I think it does perhaps the only possible job of capturing both Bobby's sense of dead-end malaise, while perhaps just offering a glimpse of hope somewhere near the end.

Donovan Leitch: Atlantis.

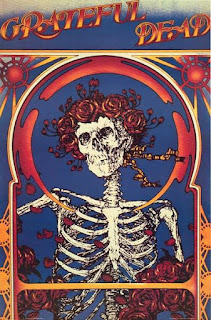

If it makes any kind of sense that Golding's Lord of the Flies is the harbinger symbol, or change agent, for King's novel, then it would have to be the 60s decade itself which serves as both symbolic gauntlet and driving crucible which every cast member has to run through. This is certainly true of the title story in the book, Hearts in Atlantis. In the opening paragraph to that novelette, King writes: "When I...talk about the sixties - when I even try to think about them - I am overcome by horror and hilarity. I see bell-bottom pants and Earth Shoes. I smell pot and patchouli, incense and peppermints. And I hear Donovan Leitch singing his sweet and stupid song about the continent of Atlantis, lyrics that still profound to me in the watches of the night, when I can't sleep (327)".

If it makes any kind of sense that Golding's Lord of the Flies is the harbinger symbol, or change agent, for King's novel, then it would have to be the 60s decade itself which serves as both symbolic gauntlet and driving crucible which every cast member has to run through. This is certainly true of the title story in the book, Hearts in Atlantis. In the opening paragraph to that novelette, King writes: "When I...talk about the sixties - when I even try to think about them - I am overcome by horror and hilarity. I see bell-bottom pants and Earth Shoes. I smell pot and patchouli, incense and peppermints. And I hear Donovan Leitch singing his sweet and stupid song about the continent of Atlantis, lyrics that still profound to me in the watches of the night, when I can't sleep (327)".It's from this point on that the decade itself sort of steps forward and becomes its own sort of player in the main action. The next few stories will feature character who are already caught up the fast current of events from that moment in time. It's up for debate if the Leitch song is the best segue song to mark this transition in the text. I've listened to it, and, yeah, I've heard better. The trouble is I couldn't find any other song as thematically appropriate as the one King chose. So, there it is, for better or worse.

Dave Brubeck: Take Five.

The second story in the book centers on the exploits of Peter Riley. He's a college student at the University of Maine in Orono. The story chronicles an event that happened to him during the course of one semester in the year 1966. In some ways Pete is the most ordinary character we meet during the novel. He's just one of the guys, trying to make his way through life, while also knowing when to keep his head down. As Pete explains in his own words, "I learned a lot in college, the very least of it in the classrooms...But before I learned any of those things, I learned about he pleasures and dangers of Hearts. There were sixteen rooms holding thirty-two boys on the third floor of Chamberlain Hall in the fall of 1966; by January of 1967, nineteen of those boys had either moved or flunked out, victims of Hearts. It swept through us that fall like a virulent strain of influenza (329)".

The instigating moment comes from a card-shark style motor-mouth known as Ronnie Malenfant. In the great pantheon of school bullies, what makes Ronnie stand out is the fact the he earns the title, yet he subverts the role. He has all the vices and prejudices of your typical juvenile delinquent, even down to some unrepeatable opinions about Martin Luther King. The difference is that whenever Ronnie is on-stage, no matter what he's doing, or how much tough-talk he spouts, I never got the impression that I was dealing with a physically strong individual. To this day I have the idea that if I were to just walk it right to him, Ronnie would cave almost in an instant. His gift for the gab would start to work a mile a minute in an effort to try and get him out of a scarp he knew he couldn't survive. Instead, Ronnie has found other ways of ruling the roost. He plays cards. The one game he seems to have an eerie kind of genius for is a game called Hearts.

A friend of Pete's "once said Whist is Bridge for dopes and Hearts is Bridge for real dopes. You'll get no argument from me, although that kind of misses the point. Hearts is fun, that's the point, and when you play it for money - a nickel a point was the going rate on Chamberlain Three - it quickly becomes compulsive. The ideal number of players is four. All the cards are dealt out and then played in tricks. Each hand amounts to twenty-six total points: thirteen hearts at a point each, and the queen of spades...worth thirteen points all by herself. The game ends when one of the players tops a hundred points. The winner is the player with the lowest score. In our marathons, each of the other three players would cough up based on the difference between his score and the winner's score. If, for example, the difference between my score and Skip's was twenty points at the end of the game, I had to pay him a dollar at the going rate of a nickel a point. Chump-change, you'd say now, but this was 1966, and a dollar wasn't just change to the work-study chumps who lived on Chamberlain Three (329-30)".

It may not be noticeable at first, though on repeated readings, it's obvious to see the twisted logic in the whole setup. Ronnie is a bully of the first degree, yet he can't hold onto his authority through sheer brute force like others. Still, like all bullies, he craves that overwhelming sense of power. In order to both achieve and secure that power, however, he has to find some other way of drawing people into and under his sway that doesn't involve using his fists, a tactic that would result in his certain defeat. His skill at cards and numbers is the one sure way he has of commanding a room. Without lifting a finger, Ronnie is able to lure unsuspecting dupes into his orbit where he can then rule and live like a tinpot king, complete with an imaginary, aluminum crow.

This is something Pete Riley is more than aware of, and he wants no part of it. Ronnie is aware of Pete's awareness, and he also knows other ways of drawing in a mark. In a very clever demonstration of reverse psychology, Ronnie is able to use Pete's loathing of him to draw the fly into the web. The worst part is it works too. Pretty soon, Pete admits to the audience, "My geology text lay forgotten on the sofa behind me. I wanted my quarter back, and a few more to jingle beside it. What I wanted even more was to school Ronnie Malenfant (354)". A few paragraphs later, Pete gives us this insight into his thought process, "I wouldn't make much from Ronnie, but the other two would be coughing up blood: over five bucks between them. And I'd get to see Ronnie's face change. That's what I wanted the most, to see the gloat go out and the goat come in. I wanted to shut him up (356)".

It's the drive to see a bully humbled that gets Pete hooked in, and which has play right into Ronnie's hands. There's an ultimate form at irony at work during the whole proceedings, however. Ronnie may have found a perfect way to rule the roost, and found a new mark into the bargain. Still, the joke is on both of them. Ronnie may have created a perfect system for holding onto what he believes is power in the dorm room, though in reality what he's set into motion amounts to a kind of perfect, accidental death trap. What Ronnie sets in motion is a mania for the game of Hearts that pretty soon manages to engulf even him, so that things soon begin to spiral even out of his control. There is a spectral presence looming over all of this. It casts a kind of pall over every student in the dorm as the game plays on. It's a potential death-sentence for those who fall victim to it, they know it, and yet a lot of the students seem indifferent to it as the game goes on, Pete included. That specter is best summed up in one word: Vietnam.

I chose the Brubeck piece to symbolize this opening sequence of the novelette because the way it starts out slow, and begins to build as the consequences begin to grow steadily more dire. The atmosphere sounds calm, yet there's a palpable sense of tension in the air that spikes as each hand is dealt. It's one of those serendipitous moments where the actual rhythm of the music itself is able to serve as punctuation for the action. It's easy to hear the sound of Joey Morello's drumbeats and see them as the players laying down their cards one after the other as tempers begin to rise, and the stakes get higher.

Credence Clearwater Revival: Fortunate Son.

There's a sequence in the Hearts segment of the novel which reads as follows: "In Vietnam the war was going well - Lyndon Johnson, on a swing through the South Pacific, said so. There were a few minor setbacks, however. The Viet Cong shot down three American Hueys practically in Saigon's back yard; a little farther out from Big S, an estimated one thousand Viet Cong soldiers kicked the shit out of at least twice that number of South Vietnamese regulars. In the Mekong Delta, U.S. gunships sank a hundred and twenty Viet Cong river patrol boats which turned out to contain - whoops - large numbers of refugee children. America lost its four hundredth plane of the of the war that October, an F-105 Thunderchief. Th pilot parachuted to safety. In Manila, South Vietnam's Prime Minister, Nguyen Cao Ky, insisted that he was not a crook. Neither were the members of his cabinet, he said, and the fact that a dozen or so cabinet members resigned while Ky was in the Philippines was just coincidence.

"In San Diego, Bob Hope did a show for Army boys headed in-country. "I wanted to call Bing and send him along with you," Bob said, "but that pipe-smoking son of gun has unlisted his number." The Army boys roared with laughter. ? and the Mysterians ruled the radio. Their song, "96 Tears", was a monster hit. They never had another one.

"In Honolulu hula-hula girls greeted President Johnson. At the U.N., Secretary General U Thant was pleading with American representative Arthur Goldberg to stop, at least temporarily, the bombing of North Vietnam. Arthur Goldberg got in touch with the Great White Father in Hawaii to relay Thant's request. The Great White Father, perhaps still wearing his lei, said no way, we'd stop when the Viet Cong stopped, but in the meantime they were going to cry 96 tears. At least 96. (Johnson did a brief clumsy shimmy with the hula-hula girls; I remember watching that on The Huntley-Brinkley Report and thinking he danced like every other white guy I knew...which was, incidentally, all the white guys I knew.)

"In Greenwich Village a peace march was broken up by the police. The marchers had no permit, the police said. In San Francisco war protesters carrying plastic skulls on sticks and wearing whiteface like a troupe of mimes were dispersed by teargas. In Denver police tore down thousands of posters advertising an antiwar rally at Chautauqua Park in Boulder. The police had discovered a statute forbidding the posting of such bills. The statue did not, the Denver Chief said, forbid posted bills which advertised movies, old clothes, drives, VFW dances, or rewards for information leading to the recovery of lost pets. Those posters, the chief explained, were not political (381-2)".

The moment is really just a catalogue of events that were happening in America during that particular year. King uses it as a way to situate his audience. A good way to look at it as the literary equivalent of a montage. It's the part in the film were all of the writer's narrative description would be shown as a series of archival clips paraded past the viewers gaze as the reels unfolded. It also serves to list the stakes that are hanging over Pete's head as his Hearts addiction intensifies. Whenever I read this segment, it's impossible for me not to hear what is perhaps the only standard song that has to go along with it. That's where Credence comes in. I know King references the song 96 Tears, however Fortunate Son was always what I heard in my mind whenever I come across that passage. There's just something about the song that carries more of an impact. The Mysterians song would just make it appear as if the whole scene were being made fun of. The alternative, on the other hand, gives it all a bit of resonance. It is one of those musical snapshots of an era, and it fits in well enough with the nature of King's narration at that point.

The Five Satins: In the Still of the Night.

Pete has at least one saving grace in the midst of the whole quagmire he finds himself in. That would be Carol Gerber. In the second part of King's novel, we catch up with her as a young college student. From what she tells us, it sounds like her own life hasn't been going too hot. So much to the point that she declares she's dropping out, mostly to commit herself full time to the peace movement. She explains her reasoning for this when she show's Pete a photo of her, Bobby, and Sully taken years ago. She explains how she was beaten up, and how Bobby carried her to safety. Pete notes that her eyes light up as she talks about the whole ordeal. It seems to have inspired her with a urge to see the right thing done, which is one of the reason's she's planning on dropping out. Pete also can't help but notice that she's still something of a torch carrier, even after all those years.

Pete has at least one saving grace in the midst of the whole quagmire he finds himself in. That would be Carol Gerber. In the second part of King's novel, we catch up with her as a young college student. From what she tells us, it sounds like her own life hasn't been going too hot. So much to the point that she declares she's dropping out, mostly to commit herself full time to the peace movement. She explains her reasoning for this when she show's Pete a photo of her, Bobby, and Sully taken years ago. She explains how she was beaten up, and how Bobby carried her to safety. Pete notes that her eyes light up as she talks about the whole ordeal. It seems to have inspired her with a urge to see the right thing done, which is one of the reason's she's planning on dropping out. Pete also can't help but notice that she's still something of a torch carrier, even after all those years. In this story she acts as the angel on Pete's right shoulder, urging him to stand up for himself and put his life back on track. This is good advice for a kid with the threat of Nam still hanging over his head. Pete never doubts what she's saying. He knows like Elvis Presley that he's "caught in a trap". Also like the King, Pete admits that he can't bring himself to walk out of it. Whenever he's with Carol, however, the idea of just laying down his cards and stepping away from the table seems as easy as basic arithmetic. Carol's voice is the single piece of advice Pete seems inclined to listen to. It even reaches a point where he begins to see her as the queen of hearts in his dreams.

I chose the Satins song as it hits the right note of Pete's unrequited love for Carol, combined with the knowledge that there's is a one night's dream, of sorts. In particular, it seemed appropriate for there last time together during one final moment of romantic love.

The Mamas and the Papas: California Dreaming.

In the end, Carol is able to leave a positive impact on Pete, even in the short amount of time they've known each other. It's over the Thanksgiving vacation, while back visiting with his folks and kin, that's Carol's words start to get to him. A seed has been planted. He finds himself resolving to knuckle under and study his eyes out if that's what it takes in order to survive in Nam era America. In addition to this, he also decides to paint a peace symbol on the back of his college jacket.

It was in listening to King's description of the main character's drive from Orono all the way back to Gates Falls that put California Dreaming in my head. There was something about the song, combined with the image of Pete making his way through the washed out and faded, yet somehow colorful back roads of New England that just made the song appropriate.

The Beatles: Rain.

One more thing happens to Pete during that Fall/Winter of 1966. It somehow winds up being the deciding event of his college life. When he returns to the UMO, his resolve begins to falter almost at once. Though perhaps crucially, it doesn't go all the way out. It's true he finds himself once more at the card tables, almost to the very minute that school is back in session. However something comes along to derail the moment when the poor hapless sap gets marched off the cliff. This is a moment King chooses to linger on, and once it plays out it is just possible to see why it is so important. It goes like this.

It involves something that happens to a character named Stokely Jones. He's not been talked about or discussed much because of how peripheral he's seemed to the main action of the story up to now. We meet him in the opening pages of the novelette as he makes his way across campus on a pair of crutches. He cuts a very anti-social figure, and as a reader I found it somewhat difficult to get a clear picture of him. However, I'm also willing to go with the idea that this might have been intentional on the writer's part. After King has introduced us to the character he keeps him well in the background of the proceedings. However he's is never shunted off-stage entirely. Ever so often he will pop up when you're least expecting him to.

The next time we see him after his first introduction is when Pete helps him retrieve a school textbook. Stoke brushes him off, but not before giving him both a piece of his mind, as well as some advice. The gist of the exchange is that Stoke is smart enough to point out to Pete that he's been roped into a scheme dreamed up by the class bully, i.e. Malenfant. As far as Stoke is concerned, Pete's misstep earns Ronnie an air of "credibility (367)". Stoke is also curious, however. He even flat out asks Pete, "Why do you waste your time (ibid)"? To which the best and lamest response he can find is "I've got plenty of time to waste (ibid)". This is all that passes between them on the matter.

The next time we see Stoke, he's in the newspaper. During one marathon hearts session a classmate spots the familiar figure as he's being led away by the police. "It was Stokely Jones III, all right...The photo wasn't much different from the one taken at East Annex during the Coleman Chemical protest. It showed the cops leading the protesters away while construction workers (a year or so later they would all be sporting small American flags on their hardhats) jeered and grinned and shook their fists. One cop was frozen in the act of reaching out toward Carol's arm...Two more cops were escorting Stoke Jones, who was back to the camera but unmistakable on his crutches. If any further identification was needed, there was that hand-drawn sparrow track on his jacket. (399-400)".

This pairing of Carol and Stoke is interesting from a thematic perspective. It could be that together both figures represent the respective change agents in Pete's story. In any case, the next time we hear from Stoke is when the reader is shown the results of a little graffiti project which curses out then president Lyndon Johnson, and also demands: "U.S. Out of Vietnam Now (464)". The stunt is enough to have the guilty party expelled when caught. Pete muses, "I've read that some criminals - perhaps a great many criminals - actually want to be caught. I think that was the case of Stoke Jones. Whatever he had come to the University of Maine looking for, he wasn't finding it. I believe he'd decided it was time to leave...and if he was going, he would make the grandest gesture a guy on crutches could manage before he did (ibid)".

In essence, what we have is a background character who also acts as what might be called a prime motivator for a lot the important turns in the plot. There is a risk that using a character in such a way can leave the author open to the charge of just creating a puppet that can be manipulated as the writer sees fit. It's happened in other cases, however this is not the general vibe I get from all the times that Stoke appears on-stage. To me it always reads like I'm observing a three-dimensional character who always keeps you guessing at his motivations. With Jones one gets the sense of those old trickster figures from ancient myth. Sometimes they take center stage, yet often they remain in the background while simultaneously having their seldom seen actions have a major impact on the direction of the plot. This is the role that Stoke seems to be carrying out during the main action of the second story in King's novel. If there is any truth to this speculation, then I wonder if it places the character as a sort of light contrast to William Golding's Lord of the Flies. Both the fictional character and the real life text either bring about or harbinger the arrival of change for the lives of the main protagonists. The difference is that with Peter Riley, things tend to take a more upbeat turn.

In essence, what we have is a background character who also acts as what might be called a prime motivator for a lot the important turns in the plot. There is a risk that using a character in such a way can leave the author open to the charge of just creating a puppet that can be manipulated as the writer sees fit. It's happened in other cases, however this is not the general vibe I get from all the times that Stoke appears on-stage. To me it always reads like I'm observing a three-dimensional character who always keeps you guessing at his motivations. With Jones one gets the sense of those old trickster figures from ancient myth. Sometimes they take center stage, yet often they remain in the background while simultaneously having their seldom seen actions have a major impact on the direction of the plot. This is the role that Stoke seems to be carrying out during the main action of the second story in King's novel. If there is any truth to this speculation, then I wonder if it places the character as a sort of light contrast to William Golding's Lord of the Flies. Both the fictional character and the real life text either bring about or harbinger the arrival of change for the lives of the main protagonists. The difference is that with Peter Riley, things tend to take a more upbeat turn.The way Stoke changes Pete's life is when he's discovered making what can only be described as a dead man's run across the entire length of the University campus in the middle of a freezing rain. He catches the attention of Pete and the other card players in the middle of their self-destructive game and manages to bring the whole thing to a stop as everyone gathers at the window to stare in a collective state of blank disbelief.

""Stoke came rapidly down the path which led from the north entrance of Chamberlain to the place where all the asphalt paths joined in the lowest part of Bennett's Run. He was wearing his old duffle coat, and it was clear he hadn't just come from the dorm; the coat was soaked through. Even through the streaming glass we could see the peace sign on his back, as black as the words which were now partly covered by a rectangle of yellow canvas (if it was still up). His wild hair was soaked into submission.

"Stoke never looked toward his KILLER PRESIDENT graffitti, just thumped on toward Bennett's Walk. He was going faster than I'd ever seen him, paying no heed to the driving rain, the rising mist, or the slop under his crutches. Did he want to fall? Was he daring the slushy crap to take him down? I don't know. Maybe he was just too deep in his own thoughts to have any idea of how fast he was moving or how bad the conditions were. Either way, he wasn't going to get far if he didn't cool it.

"Ronnie began to giggle, and the sound spread the way a little flame spreads through dry tinder. I didn't want to join in but was helpless to stop. So, I saw, was Skip. Partly because giggling is contagious, but also because it really was funny. I know how unkind that sounds, or course I do, but I've come too far not to tell the truth about that day...and this day, almost half a lifetime later. Because it still seems funny to me, I still smile when I think back to how he looked, a frantic clockwork toy in a duffle coat thudding along through the pouring rain, his crutches splashing up water as he went. You knew what was going to happen, you just knew it, and that was the funniest part of all - the question of just how far he could make it before the inevitable wipeout (471-2)".

The wipe-out does happen, of course. The fashion in which this is achieved leaves one hell of a mark on the observing occupants in the dorm; "the place turned into bedlam on the spot. Cards flew everywhere. Ashtrays spilled, and one of the glass ones (most were just those little aluminum Table Talk pie-dishes) broke. Someone fell out of his chair and began to roll around, bellowing and kicking his legs. Man, we just couldn't stop laughing (473)".

To read all this, one would think the the spirit known as Anansi, a figure of African folklore and myth, as well as a major character in Neil Gaiman's American Gods series, had snuck into the room at some point. Perhaps there can at least be some thematic-relational sense in which this is true. As I've said before, Stoke is no kind of elemental, yet there is something of the trickster in him. Like the thousand faced hero, the trickster's appearance can often change, yet the function somehow always manages to remain the same. Just as with Anansi, Thoth, Mercury, or whatever name you want to give this figure, Stokley's hi-jinks not only disrupt, they also change and reshape things. In Pete's case, they cause him and several others, even the bullying Ronnie, to dash out into the storm to perform a bit of first aid rescue. This turns out to be an act that mirrors an earlier part in the novel. Like Bobby lifting Carol to safety, Pete and company carry Stoke to the infirmary. Also, as in the earlier sequence, the same action also leaves the narrator of the the title segment changed. He somehow finds himself able to kick the card playing habit, and take part in an informal student protest along with his fellow classmates in order to defend Stoke from the authorities.

To read all this, one would think the the spirit known as Anansi, a figure of African folklore and myth, as well as a major character in Neil Gaiman's American Gods series, had snuck into the room at some point. Perhaps there can at least be some thematic-relational sense in which this is true. As I've said before, Stoke is no kind of elemental, yet there is something of the trickster in him. Like the thousand faced hero, the trickster's appearance can often change, yet the function somehow always manages to remain the same. Just as with Anansi, Thoth, Mercury, or whatever name you want to give this figure, Stokley's hi-jinks not only disrupt, they also change and reshape things. In Pete's case, they cause him and several others, even the bullying Ronnie, to dash out into the storm to perform a bit of first aid rescue. This turns out to be an act that mirrors an earlier part in the novel. Like Bobby lifting Carol to safety, Pete and company carry Stoke to the infirmary. Also, as in the earlier sequence, the same action also leaves the narrator of the the title segment changed. He somehow finds himself able to kick the card playing habit, and take part in an informal student protest along with his fellow classmates in order to defend Stoke from the authorities.It marks the conclusion of this character's arc, as well as his story. What's remarkable about it is the way King is able to do some heavy lifting of his own. The reader finds himself willing to go along with a story in which it could be argued that not much happens, and yet the writer is able to pack the second segment of the narrative with incidents that hold both the attention and interest from start to finish. Part of this may be down the curiosity that comes from the immersion in another time period. If so, then it is some thing King is able to accomplish with all the veracity of a living witness.

I chose a little known tune, Rain by the Beatles, for the way in which it makes a neat thematic connection between the action that happens during Pete's final, aborted game of Hearts, and the disorder and change Stoke is able to introduce into the proceedings. The message of the original song, in and of itself, seems to be a critique about the types of people in life who "run and hide their head" from the problems of the real world that are confronting them. That's a neat description of the exact situation that Pete and his fellow classmates find themselves caught up in. Part of the reason they get hooked on Hearts is due to their wish to hold their future responsibilities at bay. The trouble is that it's a fatal option in their case. The speaker in the Beatles song wishes to waken the drowsing characters he is addressing from their stupefied state and alert them to a wider sense of possibility. Stokely is definitely trying to stir things up at UMO, though he believes he's not making any impact, and the whole thing frustrates him to no end. It isn't until he takes a big spill that his message gets through in the most ironic fashion.

As such, due to the nature of the characters and setting in which the moment of transition occurs, it just seems fitting that an old Lennon/McCartney song should be able to match both the message and tone of the story's penultimate moment. In addition to lining up in a near perfect way with the scene's theme, the sound of the Beatles' music just somehow manages to capture the manic and crazy intensity of the episode. It does a good job of putting a soundtrack to total, crazy, gonzo bedlam.

The Doors: Break On Through to the Other Side.

One of the plot elements that has to remain front and center is the Carrying motif that King sounds throughout this work. He's able to do two things at once with this concept. Throughout the three remaining segments of the novel, King is able to foreground the motif without drawing so much attention to it that it becomes a distraction from the story he has to tell. The way he does this in both of the next two chapters, Blind Willie and Why We're in Vietnam, is by setting the event firmly in the past.

Both chapters are like short stories concerned with this single event, as told from different perspectives. In Blind Willie, we are caught up with the figure of Willie Shearman, the neighborhood bully who once beat Carol Gerber within an inch of her life. It's very rare for King to concern himself all that much with bully figures like this. They are a near constant presence in his work, and usually when he introduces them, it's often in the service of the more graphic, horror oriented elements in his work. Bill Shearman is an interesting anomaly in this pantheon, because he is one of the few times the bully figure has been allowed to progress beyond his main identifier stage, and progress as a different sort of character.

We learn that Willie took the thrashing he received at the hands of a young Bobby Garfield to heart. Ever since that day, he's quietly tried to turn things around for himself. He's managed to hold on to an old baseball glove that Bobby threw away, and has carried it with him ever since. Eventually Bill found himself caught in the draft and serving next to Bobby's old friend John Sullivan, as well as a motor-mouth card-shark named Ronnie Malenfant. It's during their time in the Green that Willie is able to save Sully-John's life after the latter receives a near-fatal injury while their unit is trying to make a getaway. When Bill caught a glimpse of Sully writhing in agony on the ground, he was able to lift the poor guy in his arms, and run with him all the way to a more than helpful pair of rescue choppers. It's a moment that leaves an impact on both men, and in Blind Willies, we discover Shearman as someone obsessed with the idea of penance. For someone who spent most of his life beating up on others smaller than himself, this can at least make a certain amount of sense.

He makes his living as a street beggar under the moniker of Blind Willie Garfield, using Bobby's old glove as a prop in the act. The whole setup is apparently Willie's way of an ongoing apology. While the circumstances are odd in the extreme, King is able to make the reader buy into it due to his ability to display character in such a way that gets the audience on his side. It's because of this often overlooked skill that we are able to go along with Bill's hijinks, and even sympathize with him to a somewhat surprising amount. It doesn't hurt that Nam left Bill with a condition in which he temporarily goes blind for at least a part of the day. In spite of these setbacks, Blind Will Shearman comes off as one of the most held-together characters in the novel. When we are -re-introduced to him, the character has already come out of a long struggle with himself, and has managed to find a strange, yet genuine level of satisfaction. It's King showing us a moment of successful transition in a way that perhaps only he could carry off.

There is a moment in Blind Willie where the title character hears Jim Morrison singing in his head about how the day destroys the night, night divides the day. In retrospect I think it's fitting comment on the changes that Willie has undergone as a character, as well as acknowledging the trials he had to endure as a soldier. For that reason I would have to use the Doors' song as a musical marker for this particular chapter of the novel.

The Doors: L.A. Woman/The Who: Won't Get Fooled Again/The Platters: Twilight Time (Reprise).

It is a different Morrison number that helps set a different tone and key for the penultimate chapter of the novel, Why We're in Vietnam. This segment focuses on the same carrying motif from the perspective of a different character, Bobby's old friend John Sullivan. He was the one whose life was saved by Bill Shearman back in Nam. In this chapter we see that event from his perspective, and how it has shaped him.

It is a different Morrison number that helps set a different tone and key for the penultimate chapter of the novel, Why We're in Vietnam. This segment focuses on the same carrying motif from the perspective of a different character, Bobby's old friend John Sullivan. He was the one whose life was saved by Bill Shearman back in Nam. In this chapter we see that event from his perspective, and how it has shaped him.In many was, Sully John comes off as the exact polar opposite of Willie. His whole experience of Vietnam left him scarred both physically and mentally. He has quiet moments of explosive anger towards even close friends and acquaintances. It doesn't help that he brought back a ghoulish kind of souvenir from the battlefield. She's a girl whose name he never knew. They met just on the outskirts of a village in a place called Dong Ha province. She came running up to his battalion, possibly looking for help and assistance. There were a lot of things Sully was never able to find out about her situation. Either way, Malenfant bayoneted her right in front of his eyes. Ever since he left the Green, Sully is sometimes able to catch sight of her here and there. Sometimes she'll be standing in the middle of a public street, or else ensconced in the bleachers of a sports events. Either way, it's the same girl, the same look on her face, and always whenever Sully spots her, her eyes always meet his dead-on. These days, however, whenever she makes an appearance he's less inclined to lose his wits and cause a scene in front of everyone else, and to her credit, she's been visiting less often.

There are still the occasional moods swings. Those also come with less frequency. It only tends to happen now whenever he thinks back on his days In Country. His current situation is or isn't dire, though if you go back and examine the course of his character trajectory, things begin to come into more focus. When we first meet Sully in Low Men in Yellow Coats, he is something of the All-American boy in the power trio he forms with Bobby and Carol, whereas his other two friends are more self-aware, and have struggles of their own to deal with, Sully seems very much like an establishment oriented kid. He tows most of the official lines, and does little to rock the boat. When the Vietnam War kicks off he signs up without once bothering to question the logic of the conflict. It seems to be this sense of blind loyalty that proves to be Sully's greatest fault. If this is the case, then perhaps it's the real explanation for his behavior when we catch up with him as an adult. Everything about the character gives the idea of a bitter and broken boy scout who feels betrayed by all the authority figures he was told to look up to.

Recently, Sully's invisible visitor has been called back from the aether of his memories by having to attend the funeral of one of his war buddies from Nam. He gets stuck in a traffic jam on his way home from the ceremony. As he sits in traffic he reminisces about his time in the field while the girl who isn't there sits and listens with implacable patience, neither saying anything, nor showing any signs of agreement or disapproval. When memory lane starts to get to be a bit too much for his liking, Sully exits his car to get some air. He notices a woman in the distance who reminds him of Carol Gerber. The last he's heard from her, she'd gotten involved in one of those radical communes that tossed bombs into public places. They said she'd been killed in a shoot-out with the FBI some time back. Yet here she is, alive and stuck in the same gridlock as himself. As Sully heads toward her something falls out of the sky and buries itself in her head. The object is a cell phone, sticking out of the unknown woman's skull like some kind of of ghoulish antennae.

When I read that scene, it was easy to here Ray Manzarek's discordant, opening organ notes as the scene played out. I think at least the opening moments of L.A. Woman provide the perfect soundtrack to the instant when the detritus and equipment of late 90s modernity inexplicably start to fall from the sky all around as Sully runs for his life. It's one of those left-field moments that King likes to pile on every now and then. Whether this scene works could very well depend upon the mileage or imaginative capacity of the reader. I'm willing to go along with it because while it is unusual, it does tie into the message King is trying to drive home. This is born out by how the scene quickly jumps from Sully trying evade a falling sky all the way back to a moment after the funeral where he's catching up with another old acquaintance.

It's during that flashback that King quietly expands on his message of the faults of the 90s age. This is far from virgin territory for the writer, and he's tackled it in a number of ways throughout his work. Reading it now, I wonder what King would have to say in a historical moment when it seems like a lot of the old struggles from the 60s seem to be making a comeback on the world stage. Would he be so quick to call the current generation lazy? Perhaps he would have said something more along the lines how he can't believe the way the past could catch up with everyone, to the point that a lot of old faces are having to once more take up the same battles like before. I can't help thinking that if he wrote this story today, his tone would be a lot more cautious, while issuing something of a challenge to his readers about taking their stand.

After this moment we transition back to Sully surrounded by the a plummeting fallout of that era's material wealth. In this penultimate moment, it's the Who's Won't Get Fooled Again that punctuates the action. It isn't until the woman from Sully's mind speaks up and invites to keep him safe that the soundtrack in my head shifts. Without giving away any spoilers, I'll just that the ending of this chapter is that part of the ending I can see in my mind like a made-for-TV tableaux featuring Sully. As we pull away from the scene, and up into a sky where dusk is already in full bloom, it's the Platter's Twilight Time that comes back on the soundtrack. It's really more a musical interlude or segue sequence than anything else. It sounds like the best possible transition for the action to the book's final chapter.

Don Henley: Boys of Summer (Reprise).

In the novel's final, epilogue segment, we catch up once more with Bobby and Carol. They each appear to have gone their separate ways, therefore they've found themselves once more retracing old steps and relationships. As Bobby himself observes, "a tendril of that old magic had reached out and touched him. Come on, it had whispered. Come on, Bobby, come on, you bastard, come home. So here he was, back in Harwich. He had honored his old friend, he had had himself a little sightseeing tour of the old town (and without misting up a single time), and now it was almost time to go (659)". Before that, however, Bobby and Carol have some catching up to do.

In the novel's final, epilogue segment, we catch up once more with Bobby and Carol. They each appear to have gone their separate ways, therefore they've found themselves once more retracing old steps and relationships. As Bobby himself observes, "a tendril of that old magic had reached out and touched him. Come on, it had whispered. Come on, Bobby, come on, you bastard, come home. So here he was, back in Harwich. He had honored his old friend, he had had himself a little sightseeing tour of the old town (and without misting up a single time), and now it was almost time to go (659)". Before that, however, Bobby and Carol have some catching up to do. It is just possible to accuse the author of falling into sentimentalism with these closing moments. Some may even go as far as calling it a stock situation. My only response to that is to state that if King is indeed composing a stock situation, then I almost want to say that a distinction of difference should be made between the presence of a fictional trope and those moment when an author is just phoning it all in. There are plenty of good examples of the kind of lazy writing that King could be accused of. The latest, and hopefully final Star Wars film is the current prize pick for this category. The point, however, is that I never once felt that King was running on auto-pilot with the finale of this late 90s entry.

The reunion and denouement between Bobby and Carol does fits such critical terms as poignant and heartfelt. The difference is that King manages to never make any serious misstep in the final pages that I'm aware of. Instead, I was left with a sense of two flesh and blood individuals bridging the gap of years, while quietly mending old scars. I can even recall one fellow blogger comment citing a specific plot point. It's the moment where the two characters discover Ted has left behind Bobby's old glove, with a message in it for both of them. I've tried to find exactly where the comment was made, and ran out of luck, yet I remember the basic gist of the statement itself. They said it implied that the subtext of the scene was that their might still be a happy ending for the two old lovers, and that even when he wasn't present, Ted Braughtigan was still finding ways of mending fences. All of which is to say that I'm forced to call the closer a success, and one that does the even more important job of bolstering all the rest of what's come before.

With this final scene, I am forced once more to go right back to where it all started, with Don Henley's 1984 hit single. I've chosen this song as a bookend for several reasons. The first is that the song itself is still good, even after all these years. The second has to do with the way it serves as a neat summation of the not just the message of the ending, but also the entirety of King's novel. The basic idea at the back of Henley's lyrics is about holding on to the ideals of the past even as the years fly by. It's short, simple, some may even call it crude to the point of being simplistic. All I know is that it makes for a killer soundtrack, both as a song in its own right, and as an unintentional, yet somewhat brilliant commentary on Stephen King's Hearts in Atlantis.

Conclusion.

In an old paperback edition of his 1998 novel Bag of Bones, King included an afterword about the making of Atlantis. He tells an interesting story of how this strange hybrid of a novel came to be: "Between bouts of working on Bag of Bones...I wrote a story called "Hearts in Atlantis." It was one of my "little novels," a story too long to be short and too short to be really long, as in novel length. During a career in which I have been routinely accused of writing to outrageous lengths, (think The Stand, It, and The Tommyknockers), I have produced about a dozen of these little novels, saving most aside for their own special collections. The first "little novel collection" was Different Seasons; the second was Four Past Midnight. I like those two books; the stories in them are among my very favorite works. I had no intention of publishing such a collection to follow Bag of Bones, though, because I had no longer stories; the cupboard was bare.

In an old paperback edition of his 1998 novel Bag of Bones, King included an afterword about the making of Atlantis. He tells an interesting story of how this strange hybrid of a novel came to be: "Between bouts of working on Bag of Bones...I wrote a story called "Hearts in Atlantis." It was one of my "little novels," a story too long to be short and too short to be really long, as in novel length. During a career in which I have been routinely accused of writing to outrageous lengths, (think The Stand, It, and The Tommyknockers), I have produced about a dozen of these little novels, saving most aside for their own special collections. The first "little novel collection" was Different Seasons; the second was Four Past Midnight. I like those two books; the stories in them are among my very favorite works. I had no intention of publishing such a collection to follow Bag of Bones, though, because I had no longer stories; the cupboard was bare."Then came "Hearts in Atlantis," and it unlocked something in me that had been waiting patiently to find expression for thirty years or more. I was a child of the sixties, a child of Viet Nam as well, and have all through my career wished I could write about those times and those events, from the Fish Cheer to the fall of Saigon to the passing of bell-bottom pants and disco funk. I wanted, in short, to write about my own generation - what writer does not - but felt that if I tried, I would make a miserable hash of it. I wasn't able to imagine, for instance, writing a story in which a character flashed the peace sign or said "Hey...groovy!"

"Of Los Angeles, Gertrude Stein said: "There is no there there." That's how I feel about the sixties, when the consciousness of my generation was really formed, and about the years after the sixties, when we won our few victories and suffered our many appalling defeats. It was easier to imagine swallowing a brick than it was to imagine writing about how America's first post-World War II generation moved from Red Ryder air rifles to army carbines to mall arcade laser pistols. And yeah, I was afraid. Allen Ginsberg said: "I have seen the best minds of my generation rot"; I have seen some of the best writers of my generation try to write about the so-called Baby Boomers and produce nothing but bad karma laced with platitudes.

"Now I happen to think too much thinking is bad for writing, very bad and when I sat down to write "Hearts in Atlantis" I wasn't thinking about much - I was writing not to explain a whole generation but only to please myself, drawing on an incident I had observed when still a freshman in college. I had no particular plans to publish the story, but I thought it might amuse my kids. And that was how I found my way in. I began to see a way I might be able to write about what we almost had, what we lost, and we finally ended up with, and how to do it without preaching. I hate preaching in stories, what someone (it might have been Robert Bloch) called "selling your birthright for a plot of message (734-5)".